The Starting Point

In compiling a list of this kind, I had one rule: the music comes first. I have always resisted the idea of expecting music to feed or prompt an emotional state, so I tried to ask the question the other way round. Why do I want to listen to a particular work at any given moment? What is the imperative? Beethovens Hammerklavier Sonata was the name of the first piece I wrote down. Soon I had a couple of hundred absolute dead certainties and a mild sense of panic.

The categories came later, a broad and flexible way of ordering choices. Numerous works can appear under several headings. I realise this. So will the reader.

To help narrow the field, I laid down a few guidelines: no operas, as they have their own narrative already (though one or two overtures have crept in). No song cycles for the same reason, though they too slip in surreptitiously. Rather than omit the entire, rich treasury of Lieder, I have dropped a song into most sections, a change of pace and scale.

No one needs musical knowledge to read this book. There are pointers for those who want to dig deeper. All the music is easy to sample online so you can hear and read together, apart, before, after. Suggested recordings appear at the end.

These are my own preferences, so lets not talk about balance. They range from the well known to the unfamiliar. They are, with exceptions where the choice is part of a bigger enterprise, complete works for any forces. Early and Renaissance composers wrote much of their work for the church; broadly speaking this, mainly, is what has survived. I would have liked to include more from this period, but not everyone (Im told) wants a long list of masses. Baroque, too, would have been easier had I allowed myself a few Handel operas or more Bach (see below). I steered away from an overdose of symphonies they too warrant separate attention though broke that rule too. With contemporary composers I imposed a limit: only those born before 1940 (with one short-lived exception in Claude Vivier). I could as happily limit myself to include only those born after that date. Another list, another book.

Many works, their composers, their lovers, their stories, spill across each other. If this were online, the text would be pitted with embedded links. I have left those overlaps to the readers, without annotation, so they can adopt that quaint old habit of stumbling across connections for themselves.

The Omissions

No selection such as this can be right. Omissions will be shouted down, eccentric inclusions pilloried. No Dvok, no Prokofiev, no Philip Glass though they all get mentioned in dispatches, and in the index. Lists of best-known masterpieces are easy to find elsewhere, if thats what you are after. Online playlists deal with every mood and need (music to cry, sleep, hoover, eat to).

Many of the greatest works in the canon defy this sort of categorisation. These are the Alps. What is there to say about them? as Basil Bunting characterised Ezra Pounds Cantos. The symphonies of Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, Brahms, Schumann, Bruckner, Mahler, Sibelius, Shostakovich, as a start, should be in every library. A few are here. Johann Sebastian Bach is a continent apart. Could music lovers survive without the B minor Mass, the St Matthew Passion, the St John Passion, the cantatas, the motets, the Goldberg Variations, the Musical Offering, the organ chorale preludes, the French and English keyboard suites, the sonatas and partitas for solo violin and the suites for solo cello, the Brandenburg Concertos?

If there is an emphasis on chamber and piano music, it reflects my interests, as well as a preference for smaller works for private listening. We cannot all get to concert halls but, given the chance, they surely remain the best places to hear big symphonies or to meet new repertoire for the first time. Some of this music has taken a long time to work its way into my bloodstream. Theres no equivalent to speed-reading (or speed-dating for that matter) with the great works of the repertoire.

*

A short overview at the end of each section indicates some other works you might have expected to find but havent or that, after much heated debate with myself, fell into oblivion. These round-ups are intended not only to save my skin but to suggest further exploration. Pictures offer an accompanying dialogue, some literal in reference, others evocative. The book is offered in the hope of sharing music that, together with those great summits mentioned above, sustains me. It is a compendium but the lid is open. Throw out and renew as you like. If you feel moved to count, you will find that there are in fact over a hundred. My justification is that by the time you have crossed out the ones that do not speak to you, you might still secure the nominated century. This is todays list. Yesterdays or tomorrows? Another matter entirely.

The first blossom was the best blossom

For the child who never had seen an orchard;

For the youth whom whisky had led astray

The morning after was the first day.

LOUIS MACNEICE , Apple Blossom

PROTIN

Alleluia nativitas (c. 1200)

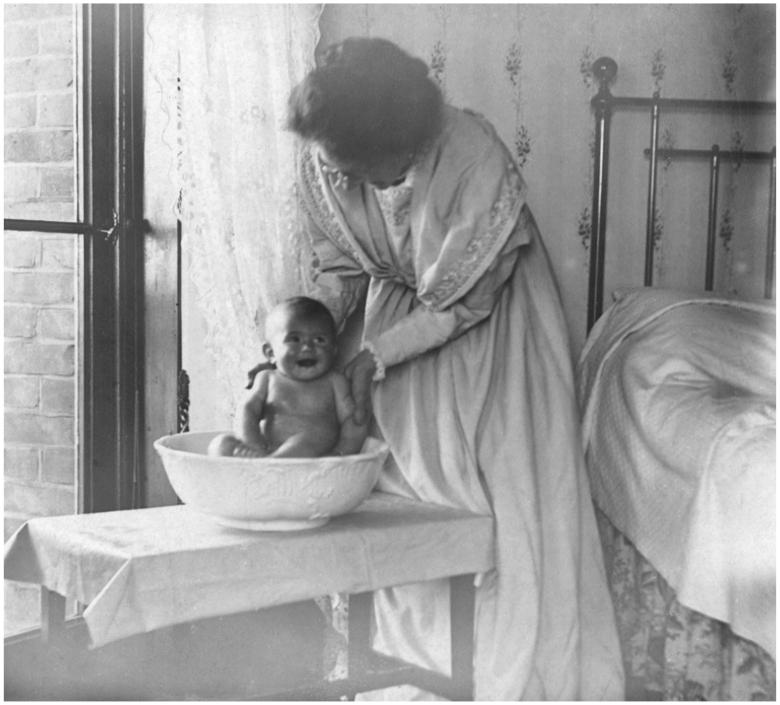

Where better to start a book about musics importance for life than with a nativity? Little is known about Protin. His birth date is uncertain. He died around 1226. He was active in Paris at the turn of the twelfth century, when the great Gothic cathedral of Notre Dame, on the le de la Cit, was under construction. In that distant time, nearly every artist composer or painter, stonemason or architect was unknown, and working, as they believed, for the glory of God. Protin is among the first we can identify, there at the dawn of Western music. We know of him thanks to a treatise dating from the thirteenth century by an English writer perhaps a travelling scholar at the University of Paris. The document, and sometimes the writer, are referred to as Anonymous IV. Copies were found in the cathedral of Bury St Edmunds, Suffolk, and eventually published in the nineteenth century. Protins three-part motet Alleluia nativitas was written for the feast day of the Virgin Mary. The three voice parts dance together in different short, rhythmic patterns and varying phrase lengths, uniting in a single line of chant, overlapping in consonance and dissonance. The effect is sprung and vital, haunting and unearthly.

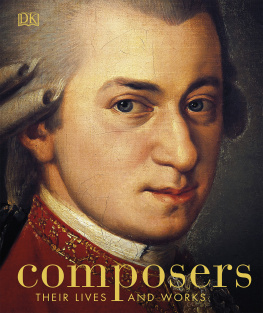

WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART

Twelve Variations on Ah vous dirai-je, Maman (17812)

In fact and in legend Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart is still the crown prince of musical prodigies. His earliest pieces, written down by his proud father Leopold (whom today we might call a Tiger Dad), date from when Mozart was aged four or five. These variations for piano, by comparison, are the work of a well-established young composer of twenty-five, having gleeful fun with a childhood song. The playfulness with which he adorns the French nursery rhyme Ah vous dirai-je, Maman (Oh shall I tell you, Mama) is evident from the solemn simplicity of the opening theme to the growing complexity as Mozart moves from rapid quavers, to lilting triplets, to busy semiquavers, now in the right hand, now in the left, with crisp ornament and abundant, run-around pleasure. The song was popular in the eighteenth century and also used for Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star, Baa, Baa, Black Sheep and other nursery songs and carols. Liszt, Dohnnyi and Saint-Sans (in