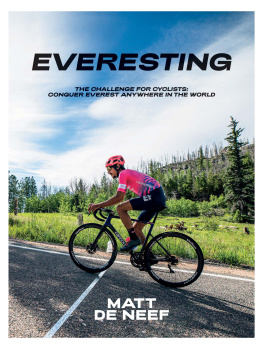

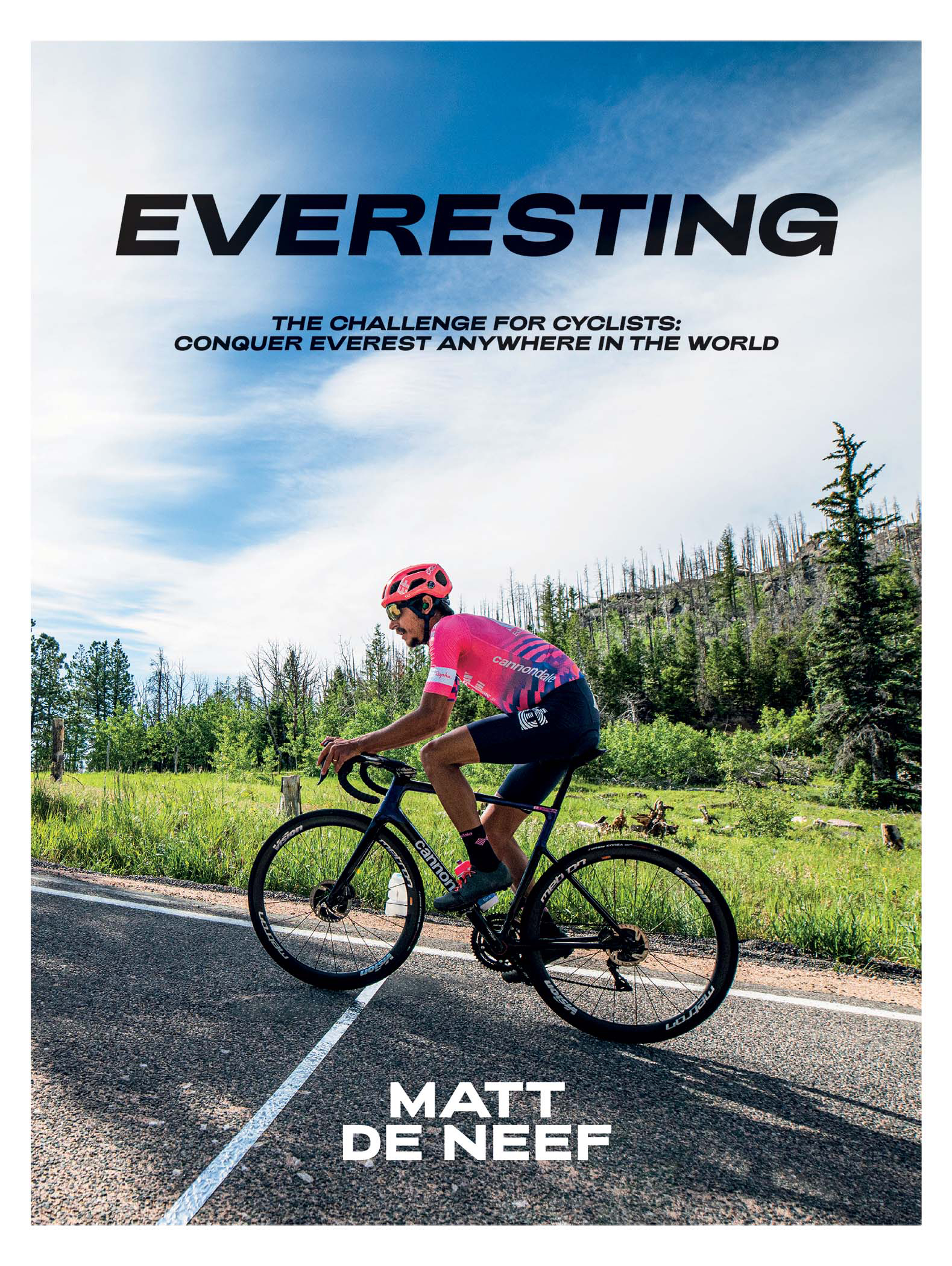

All you need to complete an Everesting is a hill you can climb over and over.

Picture this. Youre standing over your bike, moments away from starting to ride. Its almost 1 am, pitch dark, and youre completely on your own. A quiet, lonely road snakes its way unseen up the mountain in front of you, dense bush closing in on both sides. You know it will take roughly 90 minutes of riding to get to the top.

But you arent just about to climb this mountain once that would be challenging enough. No, youre about to ride it over and over again, up and down, for most of the next 24 hours. In that time youll be pushed to your absolute limit, physically and mentally, as you try to endure fatigue like youve never felt and pain in places you didnt know it was possible to feel pain.

Just the thought of it is enough to make even the most hardened athlete wince. And yet, this is a challenge cyclists have completed more than 10,000 times worldwide.

All have ridden repeats of a single hill or mountain up and down, over and over in one continuous ride, until theyve amassed 8848.86 metres (29,032 feet) of elevation gain, equivalent to the height of Earths highest peak, Mt Everest.

For some, an Everesting can take as long as 30 hours and involve more than 500 kilometres (310 miles) of riding, half of it uphill. For many, its the hardest physical challenge theyll ever face.

Its difficult to overstate the enormity of the challenge. One of the worlds toughest recreational cycling events, a French ride called La Marmotte, covers 174 kilometres (108 miles) with 5180 metres (16,990 feet) of climbing little more than half the height of Mt Everest. A particularly mountainous stage of the Tour de France, the worlds most prestigious bike race, might span 200 kilometres (124 miles) with 5000 metres (16,400 feet) of climbing also considerably less than an Everesting.

Because Everesting is a challenge defined as much by its failures as its successes, for every story of someone reaching the mythical 8848 metres, theres at least another of someone falling short. For those that do reach the height of Everest, the only prize is a place in Everestings online Hall of Fame, the official record of those who have completed this monstrous challenge.

There have been successful Everestings on road bikes, on mountain bikes, on fixed-gear bikes without brakes, and on unicycles. Everestings have been completed on foot, on skis and even via the internet. They have been completed in more than 100 countries around the world and on every continent except Antarctica.

The ascent of Mt Hotham is one of the longest and most arduous in Australia.

None of Everestings vast potential could have been known to recreational rider and Everesting founder Andy van Bergen when he clipped into his pedals at the foot of Mt Buller in the early hours of 28 February 2014. Over the next 22 hours, through darkness and daylight, through sunshine and rain, the then 34-year-old would ride lap after brutal lap of the 17-kilometre (10.5-mile) climb to the popular ski resort in the High Country of Victoria, Australia.

With that ride, he didnt just become one of the first in the world to complete an Everesting; he helped usher in a phenomenon that, in the years that followed, would take the cycling world by storm.

Andy and I have been friends since 2012. Weve ridden together countless times often uphill weve run dozens of cycling events together and weve been colleagues at the CyclingTips online magazine since 2013. In 2014 I watched with interest as Andy launched Everesting to the world, and in the years since, Ive keenly followed and reported on the challenges growth.

But in 2020, as Everestings popularity grew beyond all expectation, it was clear this challenge deserved to be documented in a more comprehensive way.

Andy remembers the start of the Everesting well. The unwelcome tap on the shoulder from his dad, Tony, waking him before midnight, after just 2 hours of sleep. Dozing in the car as Tony drove the serpentine road down the mountain. Feeling like hed been hit by a bus as he got himself ready to ride. Bidding Tony farewell just after 12.30 am, and setting off up the mountain for the first time, into the inky black.

He also remembers how quickly the self-doubt crept in. When I got started, that first kilometre or two youre just thinking What in Gods name am I doing? This is so stupid. Its pitch black. Im by myself, Im in the bush and my legs already hurt because Im not warmed up and Im tired as anything so tired and Ive got Mt Everest ahead of me to climb.

From Andys handlebars, a small, low-powered commuter light provided just enough illumination to see the road immediately before him but little else. Because the lights in front of you theres no peripheral vision, Andy recalls. So you are really enveloped in darkness. Coupled with that, youre hearing animals scurrying through the bush and bushes moving.

At around 2 am, after an hour and a half of riding, Andy reached the Mt Buller village for the first time. One lap down, seven to go. Or so he thought.

I got to the top of the first lap and checked my Garmin [GPS cycling computer] and realised that my elevation calculations had been probably a little bit optimistic, Andy says. In all my planning and mental preparation I had eight Bullers in mind. At the top of the first lap I realised instantly that I was going to be doing nine laps.

I had this feeling creeping up and I knew that this had the ability to overpower me. And so I squashed that thought straight away and just said, This is what were gonna do. Were going to get to the bottom. This first one? That was a bonus one. It doesnt count. Were starting from the bottom.

Embarking on an Everesting often means having to ride in darkness.

Back at the bottom of the hill, 2 hours after setting off, Andy said a quick hello to his dad whod been sleeping in the car. It was a brief but welcome moment of human contact amid the crushing solitude of those pitch-dark opening laps.

Through the early hours of the morning, Andy ploughed on, his tiny light cutting a narrow swathe through the black of night. On his second ascent he turned to audiobooks to distract himself from the loneliness, and from the knowledge that hed have to complete an extra lap beyond the ridiculous challenge hed already been facing.

While Andy was riding alone in Victorias north-east, he wasnt the only one attempting to climb the equivalent of Mt Everest that weekend. Hed convinced dozens of other riders to join him, each tackling their own climb at the same time.

On Mt Hotham, 65 kilometres (40 miles) to the north-east, Josh Goodall was having his own battle with the darkness.

The climb from Harrietville to Mt Hotham spans a seemingly interminable 30 kilometres (18.6 miles) and, at its peak, is the highest sealed road in Australia. More than that, its one of the countrys most challenging climbs completing a single ascent is a noteworthy achievement. That day, Josh needed to complete six laps to conquer his own personal Everest.

Next page