Contents

Guide

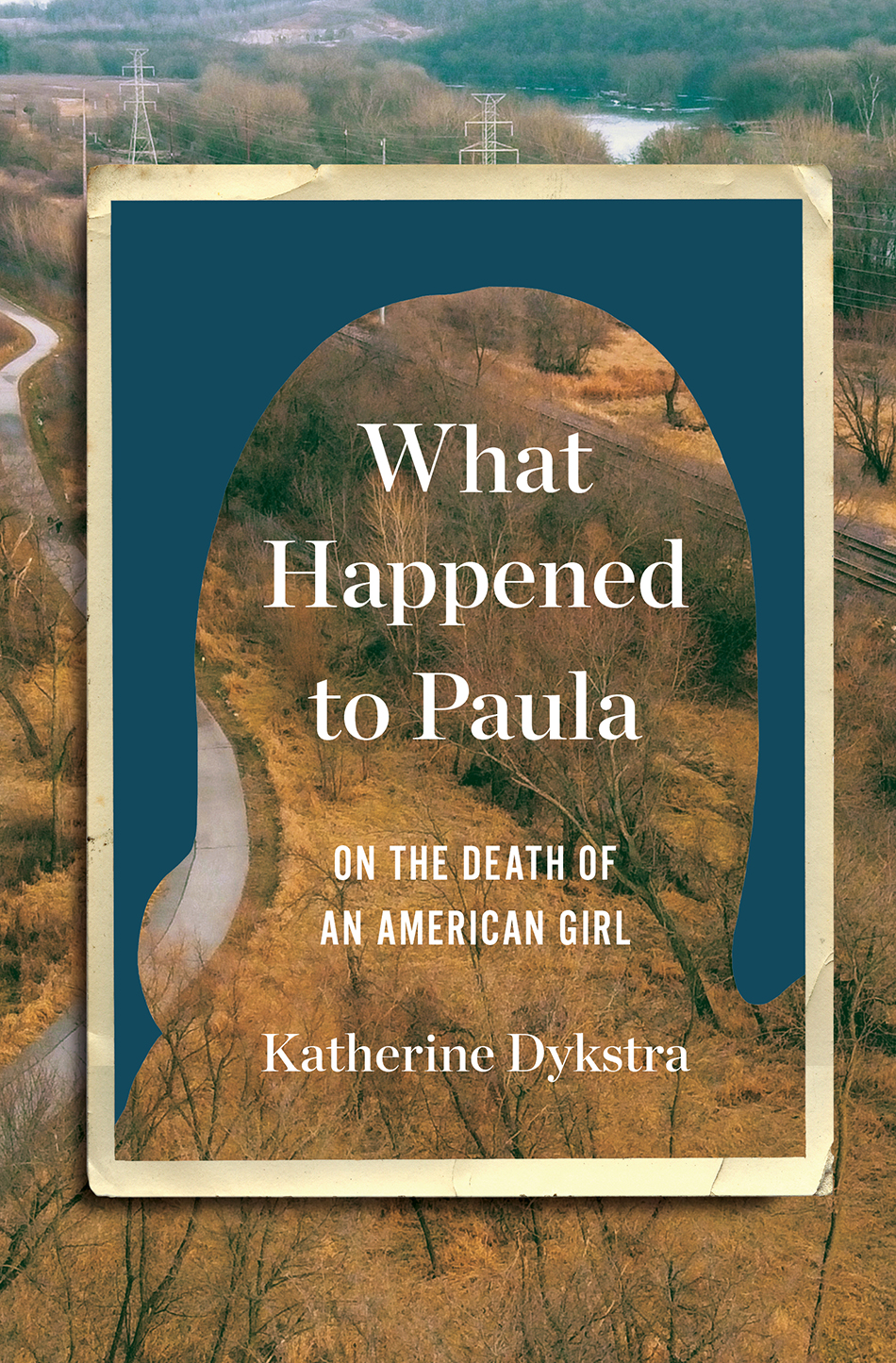

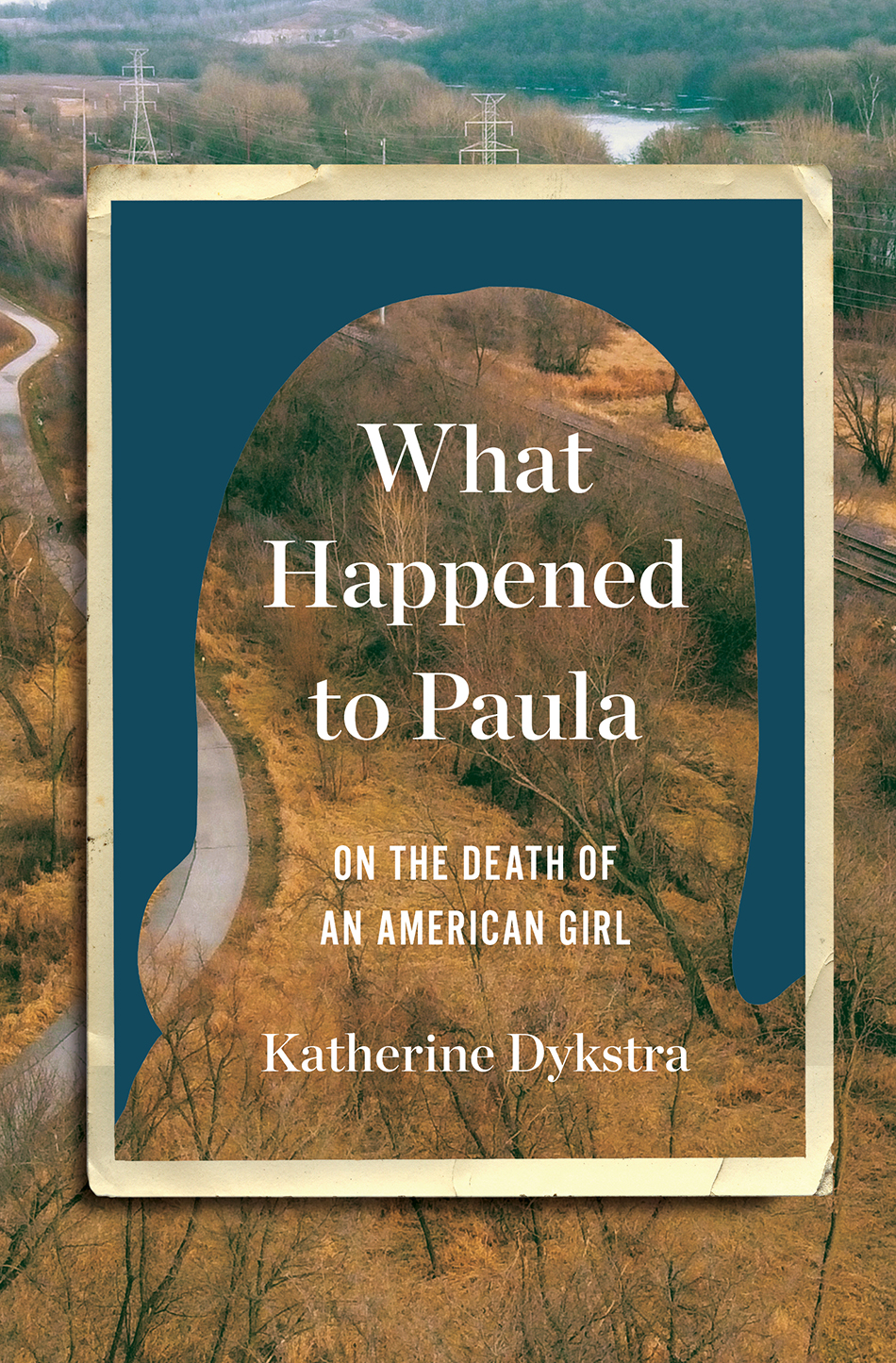

What

Happened

to

Paula

On the Death of an American Girl

Katherine Dykstra

For my children. For the Paulas.

If no one is guilty, then everyones to blame.

Susan Taylor Chehak

Contents

UNDER A WASHED-OUT WINTER SKY, I STEERED A rented car away from downtown Cedar Rapids, Iowa. My travel companion was my mother-in-law, the fiction writer Susan Taylor Chehak. Our destination: a slip of land that spooned the Cedar River. The area was just outside the city proper but felt otherworldlybarren, desolate, removed. Heading south on Otis Road, the river lazed flat and gray on our right, the Chicago & North Western railroad tracks ran silver on our left. Beyond them, Van Vechten Parks wooded darkness stretched up a steep hill. We passed a giant smoking factory, a cold freight train heavy on its track, and a handful of Canadian geese whod never made it south for the winter.

When Susan indicated, I pulled off onto Miller Lane, a narrow gravel drive that jutted up from Otis, thus far the byways only interruption. I stepped out of the car into the bitter air and followed Susan through the snow, which came up over my shoes. After intersecting with the railroad tracks, the drive continued under a gate and up through private property until it dead-ended in a horse farm on the hill. Private Drive and No Trespassing signs were nailed to trees and staked into the ground before it. We turned right at the tracks, trudging over the ties for about twenty paces until Susan stopped abruptly, turning toward the river. Here, she said.

Across the Cedar lay Mount Trashmore, the citys landfill. The puffing stacks of the Cargill cereal plant loomed in the distance. At my feet, I found a rocky crevice that sloped back down toward Otis. And there, sticking out amid a cascade of steel-gray rocks, was the culvert. A culvert is a pipe that diverts rainwater under railroad tracks in order to prevent their flooding; I had gone my whole life and had never encountered the word, but now it was everywhere. Thats where Paula Jean Oberbroecklings body had been found, just beyond the mouth of this culvert.

Paula was eighteen years old when she disappeared in the summer of 1970. Its been fifty years, and her killing has never been solved.

In the summer of 2008, seven years before I looked down into that culvert, I tagged along with my then boyfriend and his family to Cedar Rapids, where the goal was to shoot footage for a documentary film about Paula. Susan, my boyfriends mother, had attended the same high school as Paula. The two never overlapped, missing each other by a year, but in adulthood Susan had become fixated on Paulas story, filled as it was with conflicting narratives and unreliable narrators, with hearsay and speculation. Paulas was the story of a small city and small-city police, of disappointment and squandered potential, of race and class and sex. A story that became more complex the deeper one dug. A story all the more compelling for the fact that it had been mostly forgotten even though the case still yawned wide open. Susan was haunted by its lack of resolution.

The documentary was a family affairmy boyfriend, who at the time had just gotten a foothold in the film world, was the producer; his father, a longtime television showrunner, was the executive producer; and his brother, an art photographer, handled sound. They enlisted a director theyd worked with in the past, and the director brought on a cinematographer. The entire endeavor was spearheaded by Susan.

She secured interviews with Paulas familyher mother, her sister, one of her three brotherswith her friends, with a number of the detectives who worked on Paulas case. She scheduled meetings with Paulas boyfriends. She made maps of the routes taken by key players on the night of Paulas disappearance, and lists of relevant landmarks.

During the lead-up to the trip, Susan asked if I was interested in helping out with the film. As a journalist, I was equipped to conduct interviews or brainstorm lines of inquiry. But I had no interest in considering the grisly death of a young woman. It frightened me.

I was thirty-one in 2008 and in a stretch of my life I now think of as before, by which I mean before marriage, before children, and before everything that comes tethered to being responsible for the lives of others. Basically, I was in a time of my life that was easyI was in love, and I had a raft of writing and editing jobs that kept me afloat and afforded me the lease on my small Brooklyn apartment. But even more, I had the extreme privilege of not having to complicate that ease with the sticky web of real life.

It wouldnt be until aftermarriage, childrenthat my life, specifically my life as a woman, would kaleidoscope, appearing so differently that not only would I agree to involve myself in the story of this young womans death but Id find myself unable not to, convinced as I was that I owed her.

That decision would lead me down a long and circuitous path that began with the arrogant certainty that I could solve Paulas death when others had not and evolved into a different goal. For, over the course of the years I spent researching and writing Paulas story, it dawned on me that what I wanted to say about her death was less true crime and more sociological study. Meaning, though a girl had been killed, and though the details of her disappearance and death are important and will be included in the pages of this book, this is not about a murderer. I do not know who killed Paula Oberbroeckling. What I do know is that the onus of her death extends well beyond whoever dumped her body down that hill.

This is the story of the grave injustice served one girl and all the factors that conspired to allow, even ensure, that injustice. It is about the reasons it was easier for the authorities in Cedar Rapids to forget what happened to Paula than to face it. It is about the ways in which women are the same and how we are differentand the role society played then and plays now in our choices and in our opportunities or lack thereof. Its about legacy and the things that are handed down between women over generations. Its about the women in Paulas family and the women in my own. Its about women who lived in Cedar Rapids in the 1960s and women who also lost mothers, sisters, daughters to violence.

It is infuriating, but maybe it is also hopeful. My hope is that by giving Paula voice, by interrogating the generally accepted story of her life and death, by searching for nuance, I might pay my debt not only to herfor showing me that my womanhood is important and powerful and comes with responsibilitybut to the long continuum of women before me and to come. To the women who shaped memy mother, my grandmother, Susan, my friends and mentorsto women I dont even know, and to the one little girl, one day a woman, who, when I began this quest, had yet to be born.

What

Happened

to

Paula

THIS IS WHAT IS KNOWN. ON FRIDAY, JULY 10, 1970, AT 9 p.m., Paula Oberbroeckling, fresh out of high school, clocked out of her job in the Misses Sports section of Younkers department store, a regional chain, in Cedar Rapids, Iowa. Stepping out of the fluorescent lighting and into Lindale Plazas open air, Paula found Lonnie Bell waiting for her. He was leaning against his red 1960 Porsche coupe. Dusk was falling.