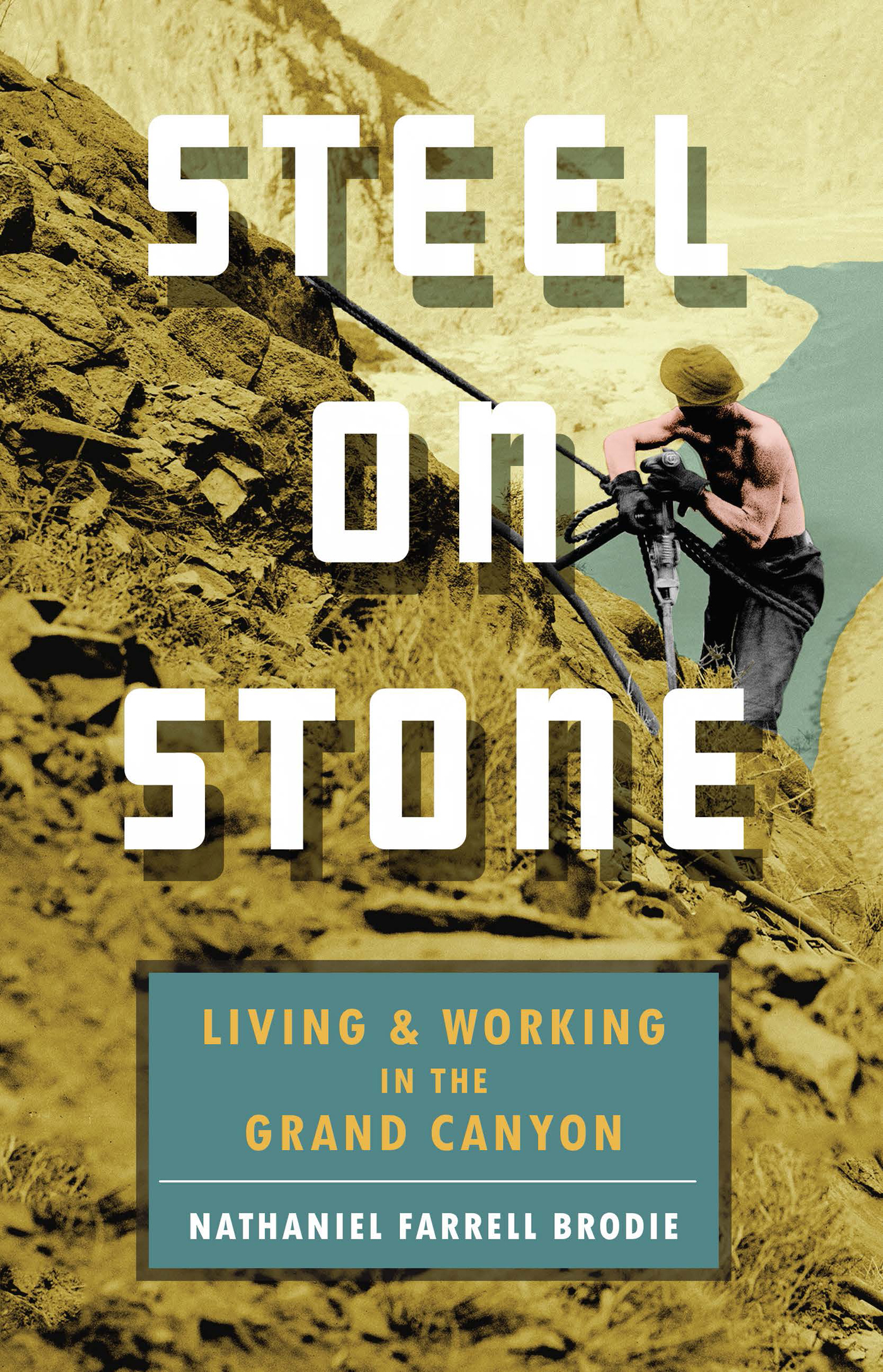

Steel on Stone

Steel on Stone

LIVING AND WORKING IN THE GRAND CANYON

NATHANIEL FARRELL BRODIE

TRINITY UNIVERSITY PRESS

San Antonio, Texas

Published by Trinity University Press

San Antonio, Texas 78212

Copyright 2019 by Nathaniel Farrell Brodie

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Book design by BookMatters

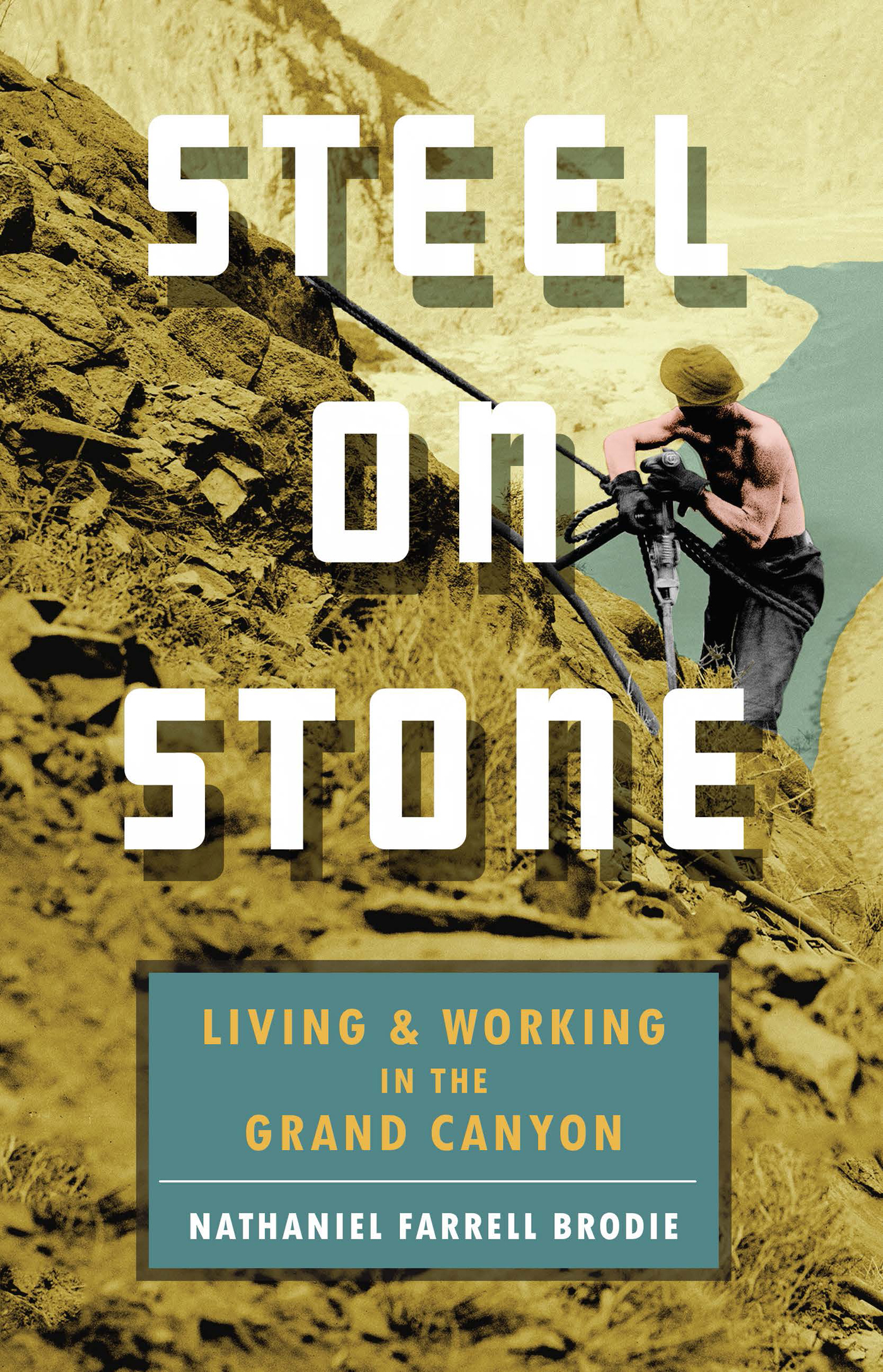

Cover design by Rebecca Lown

Cover image: River Trail construction by EWC

Company 818 enrollees. Man using a jackhammer on a steep slope, circa 1934 NPS. Grand Canyon National Park Museum Collection, no. 03968A.

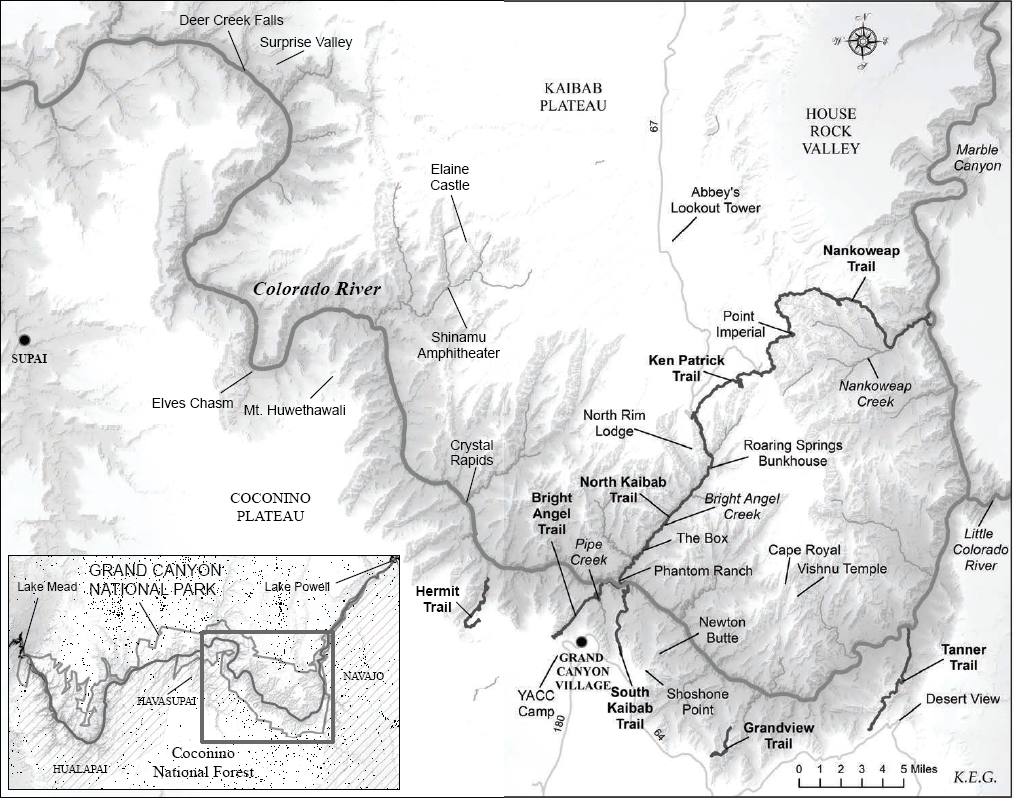

Frontis: Map created by Kelly Gleason

ISBN 978-1-59534-860-9 paperback

ISBN 978-1-59534-861-6 ebook

Trinity University Press strives to produce its books using methods and materials in an environmentally sensitive manner. We favor working with manufacturers that practice sustainable management of all natural resources, produce paper using recycled stock, and manage forests with the best possible practices for people, biodiversity, and sustainability. The press is a member of the Green Press Initiative, a nonprofit program dedicated to supporting publishers in their efforts to reduce their impacts on endangered forests, climate change, and forest-dependent communities.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI 39.48-1992.

CIP data on file at the Library of Congress

2322212019|54321

CONTENTS

To Mom and Dad, for everything

So, the world happens twice

once what we see it as;

second it legends itself

deep, the way it is.

WILLIAM STAFFORD

PRELUDE

Oh, the Grand Canyon, that must be nice. The woman sips her cocktail, tilts her head to listen to the airport intercom, then turns to me again. I have to ask, though: do you ever get sick of looking at it?

I too take a drink. I want to tell her how, standing in line at a bank, Ill overhear people mention the Grand Canyon and Ill strain to catch their conversation; how Ill find myself studying a crack in the concrete and thinking of the sudden ease with which Havasu Canyon carves through the Coconino Platform. I want to tell her that Ive split-second recognized the Canyon plastered on the side of a bus going the opposite way through five lanes of LA traffic; or that, skimming through a magazine, Ill stop, flip back a few pages, and study an advertisement containing a small picture of the Canyon in an attempt to identify where the photographer stood, at what season, at what time of day.

I want to tell her that I think the thermals coursing out of the Canyons depths spread over the entire earth before collapsing, so that wherever I am in the world, threads of scent and longing from that pion-juniper, scorched-rock air find me, move me. About that drunken night at a bar in Chicago with Michael and his girlfriend, whom he had left the Canyon to live with, and how, when she left the table to go to the bathroom, I said, I think about going back all the time, and Michael nodded and said quietly, So do I.

I want to tell her about the feeling that I have, driving north toward the Canyon on Route 64, a familiar pull that Ive known only one other time: when, driving to my childhood home in LA, I finally pass through Barstow and swing southwest toward the city, and nostalgia and homecoming swell to a crest, and right then, in the searing aridity of the Mohave Desert, Ill swear I can smell the ocean.

I want to tell her that the landscape painter Thomas Morans painting Chasm of the Colorado scarcely resembles the actual Grand Canyon and yet, in the way it scrambles scale, time, and place; fuses emotion and image; and exemplifies how ones memory collages fragments of experience into a cohesive whole, it captures the essence of how I came to know the Canyon: as a physical place, yes, but also as mutable, shifting with time and angle, different to every personality, mood, expectation, and experience, a timeless mosaic of moments, stories, ecologies, histories, images, impressions, contradictions, and memories.

But Im hesitant to reveal these things, and I figure, perhaps ungenerously, that her question itself indicates she wouldnt understand, so I tell her, No. I never do, and finish my whiskey in silence.

SPRING

The heat seethed off the rock. I willed one foot in front of the other, my head throbbing in time to the trudge of boot on dirt. Step, step, step. The air shimmered like hot oil.

So angry, I mumbled to myself. Why so angry, sun?

It was my first day of work on the Grand Canyon National Park Service Trail Crew. A few weeks earlier Id been standing in the steady rain in Olympia, Washington, using a payphone to call Will, head of Trails at Grand Canyon National Park. He offered me a job. Id recently exhausted my wanderlust and bank account after six months of travel through Asia and India, and having nothing else lined up, I accepted. Id long since sold my car, so my girlfriend, Erika, drove me down from Washington. We slept in the woods outside the park, woke early, passed through the entrance gates, parked along the side of the road near Mather Point, ducked through the last strip of pion-juniper between the road and the rim, and stared out at the Grand Canyon.

Technically, I had already once seen the Grand Canyon, as a three-year-old child. My mother tells me that I threw a tantrum because she didnt allow me to accompany my dad and older brother a few hundred yards down the Bright Angel Trail, and though I am pleased by this story, the entire trip has slipped from my mind.

I dont remember what I thought of the Canyon before I truly saw it, as though the flood of later experiences scoured away any earlier suppositions. But I suspect that the jaded arrogance of youth got the better of me and I thought the Grand Canyon would be overrateda whole park made of viewpoints, every one of them named Inspiration Point; a park for fat Vegas tourists, overcrowded and anticlimactic. I tended to avoid icons, to be suspicious of their status and, for some lamentable reason, wary of the emotions they are expected to elicit. This was probably true concerning the hoopla over the Grand Canyonall that Natural Wonder of the World, bucket-list hype had pushed it toward cultural clich.

But this second time I saw the Grand Canyonthe first time I truly saw itwill not slip from my mind. If I had considered the Grand Canyon a clich, my response to it ran the gamut of clichs: my breath failed and my mouth hung agape. It was one of those rare instances when ones surroundings still to the point of suspension, when each and every inanimate object seems imbued with an intrinsic presence, even a contentedness: the juniper berries clustered underfoot, the turkey vultures kettling on a thermal, the individual boulders spilling off the cliffs, all perfect, all perfectly in place. I leaned over the guardrail, slowly shaking my head, murmuring nothings, my hand occasionally, almost helplessly, motioning toward the river running more than a mile beneath us, the ten miles of naked rock that lay between us and the forested plateau of the North Rim.

Next page