ALSO BY NANCY RUBIN

The New Suburban Woman

The Mother Mirror

Isabella of Castile

NANCY RUBIN

iUniverse Star

New York Lincoln Shanghai

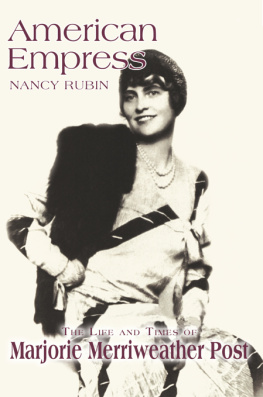

American Empress

The Life and Times of Marjorie Merriweather Post

All Rights Reserved 1995, 2004 by Nancy Rubin

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping, or by any information storage retrieval system, without the written permission of the publisher.

iUniverse Star

an iUniverse, Inc. imprint

For information address:

iUniverse, Inc.

2021 Pine Lake Road, Suite 100

Lincoln, NE 68512

www.iuniverse.com

Originally published by Villard Books

ISBN: 978-0-5957-5202-7 (ebk)

ISBN: 978-0-5953-0146-1 (sc)

For my parents,

Ethel and Stuart Zimman

Foreword

The queen is backlong live the queen! announced the syndicated newspaper columnist Suzy in December 1969. The woman she was referring to was the handsome silver-haired Marjorie Mer-riweather Post, who had just arrived in Palm Beach to open her renowned estate Mar-A-Lago for the first time in years.

Indeed, to a crowd of curious men and women who gazed at the eighty-two-year-old Mrs. Post as she stepped off her Viscount jet and climbed into a custom Cadillac that whisked her to the pink-towered Mediterranean estate on South Ocean Boulevard, she must have seemed as close to royalty as one can come in America. Marjorie, like a true monarch, was accompanied by an entourage of advisers and servants. Once settled at Mar-A-Lago, she would entertain dignitaries from foreign countriesin this instance, ambassadors from Washingtons Embassy Row. Every year they were part of a select group of men and women Marjorie invited as her guests to Palm Beachs annual American Red Cross International Ball.

To millions of Americans, the face of the still-beautiful heiress had long been a symbol of social grace, wealth, and magnanimity. For decades photographs of her, resplendent in ball gowns, ermine capes, and sable coats, her delicate features and snow-white skin enhanced by jeweled tiaras, forty-carat sapphires, and the pear-shaped diamond earrings that once belonged to Marie Antoinette, had appeared in the press. Nearly as familiar were pictures of Marjorie in tailored suits, busi-

ness dresses, and hats as she presided over charity luncheons, benefits, and other fund-raisers at her homes in Washington and Palm Beach.

Less public was Marjories role as a member of the board of directors of the General Foods Corporationthe conglomerate that had evolved from the Postum Cereal Company, the breakfast food empire of her father, C. W. Post. Although Marjorie was heiress to the Post Toasties cereal fortune, her contribution to General Foods was far from nominal. Hers had been the insistent voice that had demanded the incorporation of Birds Eye Frosted Foods into the old Postum company and transformed it into the General Foods Corporation.

Marjories various surnames from her marriagesClose, Hutton, Davies, Mayhave also floated through the public consciousness. Whatever her surname, she was always linked with social and charitable causes: the American Red Cross, the soup kitchens of the Depression, Soviet War Relief of World War II, the Boy Scouts of America, and the National Symphony Orchestra. To these and other charitable organizations Marjorie donated millions of dollars. Privately she also supported widows, orphans, and impoverished students, often without their knowledge of their benefactor. While she has always lived like a queen, observed The New York Times , she has always given like a philanthropist.

Typically it was anonymity that the publicity-shy benefactor sought for her contributions. Marjorie anonymously donated one hundred thousand dollars toward the creation of the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts. A half century earlier, during World War I, she outfitted an American Army hospital ship with equal modesty. At age twenty-seven, when Marjorie inherited her fathers fortune, she already understood that great wealth could be as much a curse as a blessing. Lets not make too much about my sponsorship because that has a tendency to drive money away, she once warned a publicist for the National Symphony Orchestra.

It was no secret that Marjorie was one of the wealthiest women in the world. While her blue eyes blazed angrily when reporters confronted her with the richest woman label, Marjorie hardly lived in a modest manner. The castles of conspicuous consumption she built in Palm Beach, Washington, and New York were famous for their opulence and fairy-tale luxury, legendary in their creature comforts and attention to the details of daily life. Perfection was the order of the day. The position of table place settings was measured with a ruler to assure uniformity.

Outside, every lawn had to be weed-free, every tree and flower a prize specimen. Inevitably the mansions Marjorie built and her lifestyle within them attracted the attention and awe of the press.

To be Marjorie Merriweather Post was to be the best and to do the best for others, but that conviction was never spoken aloud. Instead it was expressed through the philanthropists perfectionistic zeal, her persistent efforts to create a flawless and flower-filled world where all the ills of humanitywant, evil, sickness, and deathcould be at least temporarily forgotten. With that sense of personal mission, Marjorie played fairy godmother, queen, empress to the world.

Those who were guests at Marjories homes witnessed that perfectionism for themselves. They approached Mar-A-Lago through thick steel gates and a majestic bank of bowing coconut palms leading to a porte cochere and elegant entranceway. Then, passing beneath a beamed hand-painted Spanish ceiling, past coats of arms, Dresden vases, and Roman busts, they walked through carved double doors into a visual splendor so rich that it took hours to absorb.

Money, millions of dollars of it, had been spent creating the estate. Built at the height of the Roaring Twenties by the heiress and her second husband, E. F. Hutton, the palace on seventeen acres between Lake Worth and the Atlantic had been the inspiration of Florenz Ziegfelds set designer, Joseph Urban. Marjorie had furnished it with the same gaily plumed abandon as a Ziegfeld Follies stage set, filling it with furniture, tapestries, and paintings from decaying ducal palaces and stone carvings reminiscent of ancient Greece and Egypt.

The parties held at Mar-A-Lago were equally fabulous. Guest lists often exceeded two hundred and included some of Americas most celebrated tycoons, moguls, and movie stars, as well as European aristocrats. At the hour indicated on Marjories engraved invitations, her guests appeared in Mar-A-Lagos shimmering drawing rooms or upon the crescent-shaped patio beneath the mansions artificial blue moon. The men arrived in black or white ties, tuxedos, and pince-nez, and the women were draped in flowing gowns and trains, aglitter with gems, and trailed by feather boas.

To entertain her guests, Marjorie once imported a three-act comedy produced by her friend the Broadway showman Charles Dillingham. Another time she brought the Ringling Bros, and Barnum & Bailey Circus to her Florida estate. On innumerable occasions her friends Florenz Ziegfeld and Billie Burke provided costumes and set designs for amateur-night benefits. For the more ordinary costume balls of the twenties Marjories guests arrived in hand-sewn, beaded, or jeweled costumes representing the most glorious cultures of the pasteighteenth-century France, Arabia, the Orient, and the Italy of the Renaissance.

Next page