A. R. AMMONS, IN VIEW OF THE FACT

These States are the amplest poem,

Here is not merely a nation but a teeming Nation of nations.

WALT WHITMAN, CHANTS DEMOCRATIC AND

NATIVE AMERICAN, NO. 1, LEAVES OF GRASS, 1860

Intellectually I know that America is no better than any other country; emotionally I know she is better than every country.

SINCLAIR LEWIS, 1935

Damn it, I happen to love this country.

J. ROBERT OPPENHEIMER, EARLY 1950S

INTRODUCTION

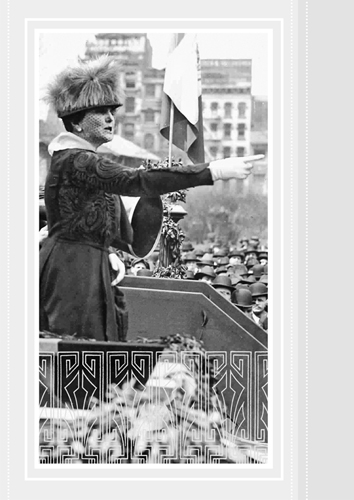

E MILY POST ENTERED THE WORLD ONLY SEVEN YEARS AFTER AMERICAS Civil War ended. Though most of her family sided with the Union, a few renegade relatives fought with the South, the staunch loyalists who survived spinning heroic stories of General Lee and his horse Traveller throughout their lives. At the time of Emilys birth in Baltimore, women were being jailed for promoting birth control for married couples; when she died in New York City, women and men, married or not, were campaigning for legalized abortion. A few years before her funeral, befuddled but fascinated, even now, by the latest technology that celebrated the ingenuity of the age, she would watch, on television, the launch of Sputnik.

She witnessed Reconstruction and Jim Crow, as well as the emergence of Martin Luther King. Her youth was shaped by the high Victorian era, cosseted by the Gilded Age, and then tossed about in the restless years culminating in World War I. Through the Roaring Twenties, the Great Depression, World War II and its domestic aftermath (all revolutions of a sort), Emily Posts Etiquette: In Society, in Business, in Politics and at Homemagisterial, impatient, collegial, and neighborlywould outlast the ages it reflected and corrected.

When it debuted in 1922, Etiquette represented a fifty-year-old woman at her wisest and a country at its wildest. The preternaturally confident author had her feet firmly planted in the Jazz Age, taking its thoughtful measure in her meticulous way. What Emily initially called her little blue book debuted in a Manhattan society intrigued by the Algonquins Round Table, where Harold Ross, editor of a new, quickly influential weekly, the New Yorker, held court with a whiskey in hand. Even as sales skyrocketed for Emily Posts guide to the good but proper life, the same decade would also nurture Dorothy Parker and Ernest Hemingway, Claudette Colbert and Clara Bow, George Gershwin and Louis Armstrong. Etiquette assumed its position within the heady cultural milieu of the 1920s, shaped by the era of its birth even while modifying it.

At its broadest, etiquettethe measure of how we treat one anotherreaches across class, race, gender, and culture. For many women, particularly (and through their transmission to their sons and husbands), Etiquette long fashioned our countrys idea and ideal of what it was to pursue a graciouspossibly even a morallife. Attention to behavior, after all, preoccupied the founders of our nation. Sixteen-year-old George Washington had written his pamphlet Rules of Civility & Decent Behaviour in Company and Conversation: A Book of Etiquette believing that everything he already knew about getting on in life was worth sharing with others.

Though never a head of state, Emily Post didnt lack for recognition. In 1976 and again in 1990, Life magazine would laud her as one of the most important Americans of the twentieth century. Etiquette, by the 1930s having sold over a million copies, would continue to be touted in the most unlikely moments and places. The list of extravagant citations the book has received in the past few years alone includes admirers as disparate as P. J. ORourke, reminiscing about learning how to fit into society through Emilys book; Joan Didion, using Etiquette to confront her grief over her spouses death; and Tim Page, a Washington Post music critic, discovering that Etiquette could help him cope with Aspergers syndrome.

In 1934, more than a decade after Etiquettes publication, Ruth Benedict, on the first page of her groundbreaking work Patterns of Culture, would state that anthropology is the study of human beings as creatures of society. Lacking the intellectual tools to articulate her own cultural philosophy, Emily Post nonetheless worked instinctively from a similar model. While Benedict was exploring customs far from her native shores, Emily was a domestic anthropologist, plumbing the homegrown soil for its indigenous fertility. She assumed early on that change was endemic to humanity, and that the human task was to adapt to it, preserving the best of what came before and integrating what superseded the past.

Emily Posts life and work would have been inconceivable without the story of Ellis Island, and the millions of immigrants who sought to become what they considered real Americans during Emilys lifetime. Between her engagement party in 1891 and the twelfth reprinting of Etiquette in 1924, Ellis Island was terra firma for more than 22 million immigrants. As a little girl, she was granted a singular privilege: while a family friend constructed its base, the Statue of Liberty functioned as her personal dollhouse, allowing the child to play inside its hollow core for weeks. When the statue was completely finished, her beloved father shared the dais with a select group, helping to dedicate Miss Liberty to the American people, especially to those future citizens streaming through the immigration corrals. Such mythical moments braid competing truths about Emily Post and the country she increasingly grew to understand and to appreciate on its own messy terms. Hers was a staggeringly ambitious hodgepodge of a nation that offered liberty and justice to allbut a justice whose blindness, for all its noble intentions, required continual redress.

How could the promise that etiquette bestows be maintained throughout the twentieth century? How, in the face of massive human and natural evils, could Americans believe that considerate social intercourse remained a significant issue? That politesse mattered? If misleadingly superficial at first glance, however, the ladys solution holds up after all. Emily Post was not alone in maintaining that the art of treating people well is the other side to the act of waging war.

CHAPTER 1

I T HAPPENED LIKE THISIN MANY RESPECTS AN OLD TALE, WITH nothing original to recommend it. A society man was caught cheating on his wife, and now, his blackmailers agreed, he would have to pay.

Emily Price Post, the adulterers wife, was furious. Shocking even herself, for the briefest of moments the usually even-tempered young matron yearned for revenge. Against her spouse, his lover, the blackmailers, and society: anyone who had contributed to this pain. Still in love with her husband, the thirty-two-year-old woman had long ago given up hope that he felt the same about her. She had made peace with her private anguish. What she had not anticipated was public humiliation.