All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher. For more information, contact:

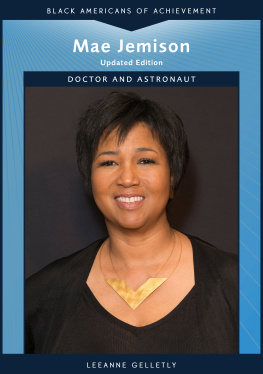

In the Early morning hours of Saturday, September 12, 1992, seven astronauts clad in bright orange space suits stood at launch pad 39-B at the Kennedy Space Center in Florida. More than 30 stories above them loomed the three main components of the space shuttle: the sleek white orbiter-the Endeavour-nestled between its two solid-fuel rocket boosters and joined to a huge rust-colored external fuel tank. One member of the Endeavour's crew, a tall, 35-year-old African American woman with short-cropped black hair and sparkling brown eyes, gazed at the massive space shuttle with special excitement. Dr. Mae Carol Jemison was poised to fulfill the dream of a lifetime.

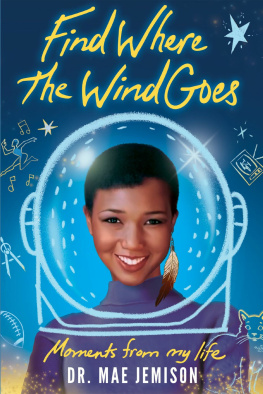

Mae Jemison poses with her fellow crewmembers prior to the historic 1992 launch of the shuttle Endeavour. Front row (from left to right): Jerome Apt, mission specialist; Curtis Brown, pilot; Back row (from left to right): J. Nan Davis, mission specialist; Mark Lee, payload commander; Robert Gibson, mission commander; Mae Jemison; and Mamoru Mohri, payload specialist.

Source: Courtesy of NASA.

Jemison was about to embark on the 50th mission of the U.S. space shuttle and would soon join the elite corps of astronauts who had journeyed into orbit. With this flight, Jemison would become a part of history as well, for she was about to become the first African American woman in space.

The U.S. space shuttle program had been in existence for more than a decade, having flown its first mission in 1981. Unlike the spacecraft developed during the early years of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA)-the U.S. space agency-the shuttle could be used for missions again and again. Because of this feature, NASA could fund many more missions and schedule far more flights into space than had ever been possible during the 1960s and '70s. Besides the Endeavour, three other orbiters-the Discovery, Atlantis, and Columbia-now regularly traveled to the stars. The space shuttle, which launched like a rocket and landed like a plane, had flown hundreds of astronauts into space and then safely returned them to Earth. But until today, none of these astronauts had been a woman of color.

Preparations for the Saturday launch had been slowed the day before because of the threat of severe thunderstorms near the Kennedy Space Center launch site. Nevertheless, technicians had managed to prepare the Endeavour for its weeklong research mission, loading the orbiter with the animals-two carp, four frogs, thousands of fruit fly larvae, and one hundred eighty hornets-that were to be used in experiments aboard the space shuttle.

By early Saturday morning, the weather had cleared and launch procedures were on schedule. The seven Endeavour astronauts entered the mid-deck of the orbiter's crew cabin and climbed into their seats, which, since the orbiter stood in an upright position, required them to lie on their backs. The Endeavour's commander, Robert L. "Hoot" Gibson, and pilot, Curtis L. Brown Jr., climbed up to their seats on the flight deck. They sat above the rest of the crew, who were strapped into seats beneath, two on the flight deck and the other three astronauts in the mid-deck of the cabin.

Finally, the launch countdown came to an end, and at 10:23 A.M. Eastern Daylight Time, the 78-ton Endeavour lifted off right on schedule and ascended into the bright blue Florida sky. During the next eight minutes, approximately 781,400 pounds of thrust powered the shuttle up to a speed of more than 17,000 miles per hour, about nine times as fast as a rifle bullet.

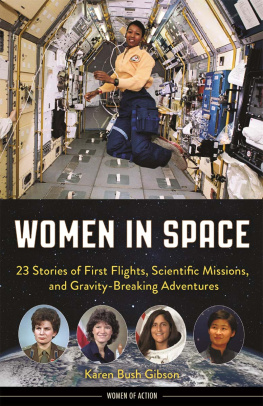

On a beautiful Florida morning the Endeavour and her crew leave the launch pad and rocket into a clear blue sky. The powerful engines must push the Endeavour to nearly 17,000 miles per hour to reach orbit.

Source: Courtesy of NASA.

The shuttle's northern course took it along the East Coast of the United States. Two minutes after launch, the solid rocket boosters separated from the orbiter and external tank, and parachuted to the Atlantic Ocean to be retrieved for reuse. About eight minutes into the flight, after pushing the Endeavour into space, the external tank, now empty, separated from the shuttle, breaking up and burning as it reentered the Earth's atmosphere.

Jemison recalled the physical effect caused by the force of liftoff: "It takes about eight minutes to get from the Kennedy Space Center into orbit. During the last four minutes, you feel a lot of pressure across your chest. You feel like you weigh about three times what you weigh on Earth." But her emotional reaction at liftoff overwhelmed her much more. In an interview with Ebony magazine, she remembered the exhilaration she felt as the Endeavour rose with a roar toward the heavens: "I had this big smile on my face. I was so excited. This is what I had wanted to do for a very long time. It was the realization of many, many dreams of many people."

At almost 260 miles above the Earth, the Endeavour was moved into a circular orbit, with its tail pointed toward the planet. This position allowed for optimal radio communication with ground control and placed the orbiter so its equipment would generate heat out toward space. The Endeavour would be traveling in a 17,500 mile-per-hour orbit around Earth, circling the Earth every 90 minutes. Its route would reach as far north as Moscow, in Russia, and as far south as the tip of South America.

Once a spaceship establishes orbit, it is in a state of continuous "free fall" around the planet. Gravity still pulls on the spacecraft, but because it is flying away from the Earth at the same rate that gravity is trying to pull it back down, weightlessness occurs. Anything not secured inside the orbiter will float as if it has no weight. After the Endeavour established orbit, its crew members unfastened their safety restraints and set to work, floating about as they attended to their tasks.

Mission specialist Mae Jemison was still stowing away the orange suits the astronauts had worn for launch when Commander "Hoot" Gibson called her to the front of the orbiter. As she reached the flight deck, the captain pointed out that they were passing over a very familiar place to Jemison-the city of Chicago. She remembers seeing the city as a contrast of gray-colored concrete buildings set against the lush greens of the farmland surrounding it. As the shuttle sped along in its orbit, that view-her first from space-vanished within minutes.

In later interviews, Jemison described her first impressions of the sights she saw from space. In one interview with People Weekly, she described the vibrant colors visible from her perch on the Endeavour: "The earth was gorgeous. There was a blue iridescent glow about the planet that was tremendous."