FOREWORD

BY ANDREW ROBERTS

No plan survives first contact with the enemy, said the great Prussian strategist Helmuth von Moltke the Elder, and this was never more true than of the Gallipoli campaign of the Great War. By April 1915, when the campaign was launched, hundreds of thousands of Allied soldiers had been killed in the trenches of the Western Front, which stretched from the English Channel coast all the way to the Swiss border. To attack the Dardanelles and thereby force the Ottoman Empire out of the war seemed like a brilliant masterstroke and so it might have been were it not for the dogged resistance of the Turkish army to the assaults launched that month on Cape Helles and Anzac Cove by the Allied expeditionary force.

The attacks were ambitious dawn amphibious assaults on a relatively unknown coast, with new troops going into action for the first time and, as it turned out, they were over-ambitious. Trenches were dug at Gallipoli and the soldiers were condemned to the same static trench warfare being endured by their comrades in France and Flanders.

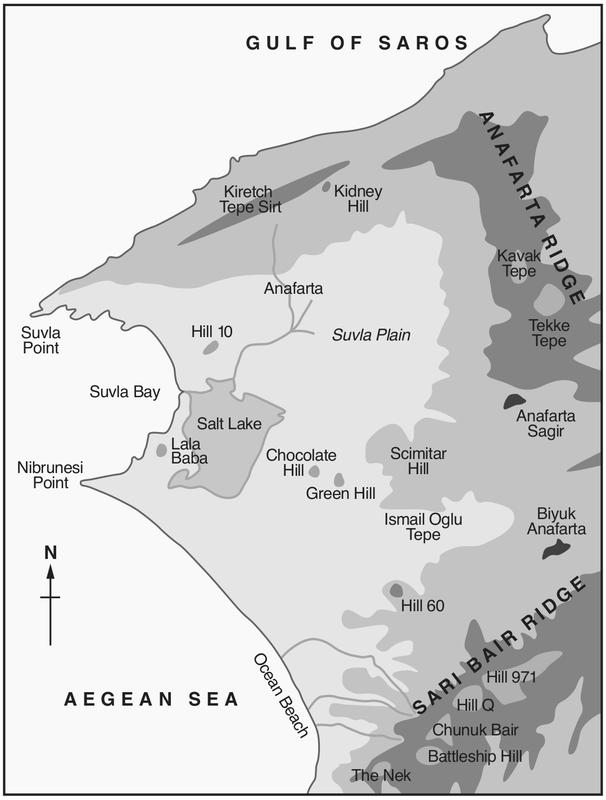

In August 1915 General Sir Ian Hamiltons Mediterranean Expeditionary Force made one last effort to break the total deadlock that had set in on the Gallipoli peninsula. An important aspect of the operation was the landing of most of the newly arrived IX Corps in Suvla Bay, with the intention that they would quickly overrun a lightly held area and assist the Australians and New Zealanders (Anzacs) as they attempted to break out of their tight little bridgehead around Anzac Cove.

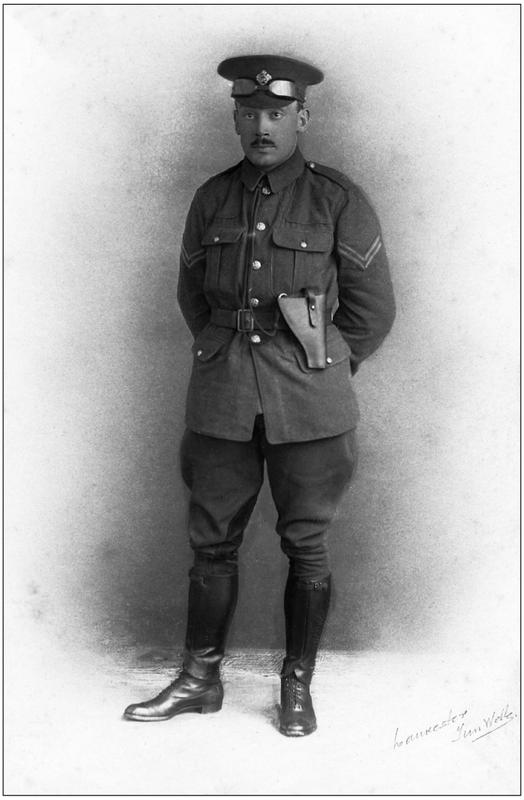

Compared to the titanic struggle on the Western Front, there is a marked lack of memoirs of frontline fighters in the Gallipoli campaign of 191516, and still fewer from the Suvla Bay aspect of that campaign. We are, therefore, very fortunate to have a vivid account by Arthur Beecroft, a 1914 volunteer signals officer in the Royal Engineers, attached to Brigadier-General William Sitwells 34th Brigade, in Major-General Frederick Hammersleys 11th ( Northern ) Division. The 10th, 11th and 13th Divisions all new formations of Kitchener volunteers made up Sir Frederick Stopfords IX Corps embarking on its first ever active service in very trying circumstances . Beecroft wrote his account for his young son.

Arthur Beecrofts earnest intent is to rescue his comrades- in-arms from subsequent accounts of the operation that heap blame upon the Suvla Bay divisions for the dismal failure of the whole August offensive, with the implication that they were just not up to the job. Australian writers have been particularly scathing about the British at Suvla, but Beecroft mounts a vigorous defence of these civilian soldiers and makes important observations on three aspects of their service: their training, their state of health, and their leadership.

Their training in England was, of course, in preparation for the trench warfare in France and Flanders. Beecroft describes it as thorough and pretty severe. These young soldiers embraced the army life with enthusiasm: Our troops, despite their embryo training, were determined to make good. What they were not ready for, just as the troops landing on 25 April 1915 were not ready for, was a full-scale amphibious assault against a defended coast. There simply was no doctrine for such a thing in 1915. Having been told by many historians that these troops could make no preparation for the landings apart from getting in and out of the boats, Beecroft adds very valuable information by telling us that his brigade made two practice landings before the real thing, with a particular emphasis on getting signals communications to follow the attacking infantry. Sadly, they made a complete hash of it on both occasions, merely reinforcing the lesson that amphibious assaults are particularly difficult and night operations even more so.

Beecroft, from his position attached to brigade headquarters, is able to comment on all the most important aspects of the operation . He reminds us that, in the final analysis, military operations are carried out by human beings who suffer from fatigue, thirst and the stress caused more by a fear of letting their comrades down than of the enemy and the battle itself. The troops landing on Suvla Bay on 6 August 1915 had slept little in the lead up to the attack. They were not used to the fierce heat of a Turkish summer and would drink the available water too quickly and be plagued thereafter by thirst. To keep the operation as secret as possible from the enemy, the attacking units were given no advance warning of the assault and all were hopelessly uncertain of what was expected of them, especially when the boats began landing in the wrong places and out of sequence.

Most importantly, these young Northerners rapidly fell victim to Eastern Mediterranean diseases. In a telling passage, Beecroft asks to what extent future historians would take account of the way food could not be conveyed from plate to mouth without becoming covered in glistening fat flies newly arrived from the open latrines used by men wracked with dysentery and diarrhoea. Beecroft reckoned that fifty per cent of the men in action on 6 9 August 1915 should have been on a medical sick list but were too keen to see action to report to their unit Medical Officer. Many of these problems could have been alleviated by a vigorous and determined leadership. Suvla Bay should be infamous for the extraordinary degree of failure in the higher levels of command. Sir Ian Hamilton had specifically requested that young, experienced generals be sent out from France to carry out this difficult operation, but he was flatly refused until after it was too late.

Beecroft hints at failures at the level of corps, division and brigade. General Stopford was appointed by seniority but had never commanded fighting troops in action in his long career. General Hammersley, as everyone knew, had suffered a severe nervous breakdown at Aldershot in 1911 and had to be physically restrained in a mental asylum. Writing to his chief, one of Ian Hamiltons officers would later say, I thought it was a wicked thing ever to have sent him out there. Beecroft often mentions My General, meaning William Sitwell, and his incapacity to grasp the wonders of the telephone. This dug out general had never been equal to such a strain. As the battle plan unravelled, Sitwell looked old and haggard, worn out with worry and physical exhaustion. Beecroft was in a good position to see how brigade headquarters, despite its responsible Brigade Major and younger staff officers, simply ceased to function as a directing body with such a commander. There is no sense of blame attached to these men so completely out of their depth; rather the blame rested with the authorities in London who expected Hamilton to achieve great things with the barest minimum of resources.

Beecroft ends by making many interesting observations on military psychology and on writers who opine on the terror of battle. Unlike them, he remembers fondly how the thin line fought on with true Northern fortitude. Their failure was only a reflection on the training of Kitcheners army, not its spirit. In this centenary year, the discovery and release of such an important new memoir is a major publishing event, providing a significant increase in our knowledge of a generally under-appreciated part of the Great War.