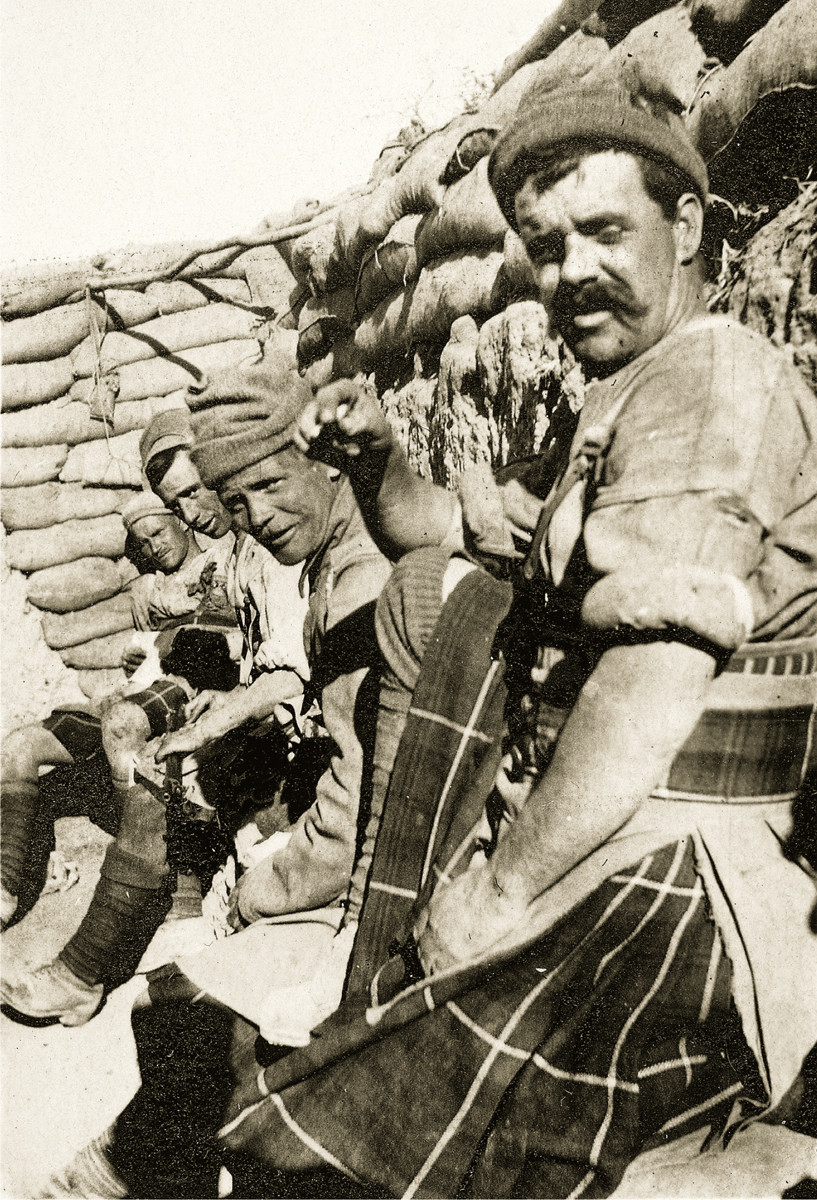

A Senegalese batman to the French General Ganeval. Ganeval was killed by a sniper in June 1915.

Lieutenant Colonel Charles Ryan: an experienced soldier, but the conditions made this a young mans war.

Oh my God, what a life this is! I shall want a six months rest cure if I survive it, and please God no more soldiering for me again. A garden and the cultivation of flowers is what I look forward to.

Major General Granville Egerton (18591951), Commanding Officer 52nd (Lowland) Division, 30 August 1915

For years after the Gallipoli campaign there existed a belief among some surviving officers that, had scarce resources been better utilised and a concerted push made at the right moment and at the right place, the campaign might have been won and strategic victory secured. It was a view submitted on occasions to Brigadier General Cecil Aspinall-Oglander, appointed to write the Official History of the ill-fated 1915 campaign, and a veteran of that expedition. It was not for the Official Historian to pour scorn on such opinions, but with twenty-first century hindsight they were entirely fanciful. If ever a campaign was doomed from the start, then the year-long slog in the Dardanelles was the case in point. Anyone who believed otherwise was blinded by over-optimism and had never stood on the regions baked and arid ground or been privy to no more than could be discerned from a stretch of trench.

The position occupied by our troops presented a military situation unique in history, wrote General Sir Charles Monro in March 1916. Monro had been brought in to take a grip on the deteriorating situation on the Gallipoli Peninsula, and he had quickly concluded that evacuation was the only option. Within weeks of his arrival, all Allied troops were withdrawn.

Monros views, written three months after the evacuation, were blunt. The mere fringe of the coastline had been secured. The beaches and piers upon which they depended for all requirements in personnel and materiel were exposed to registered and observed Artillery fire. Our entrenchments were dominated almost throughout by the Turks. The possible Artillery positions were insufficient and defective. The Force, in short, held a line possessing every possible military defect. The position was without depth, the communications were insecure and dependent on the weather. No means existed for the concealment and deployment of fresh troops destined for the offensive, whilst the Turks enjoyed full powers of observation, abundant Artillery positions, and they had been given the time to supplement the natural advantages which the position presented by all the devices at the disposal of the Field Engineer.

The hopelessness of occupying a fringe of coastline with winter on its way was self-evident. Yet Monros damning assessment was so comprehensive, so irrevocable, that it raises the question then, as it does today: what on earth were we doing there in the first place?

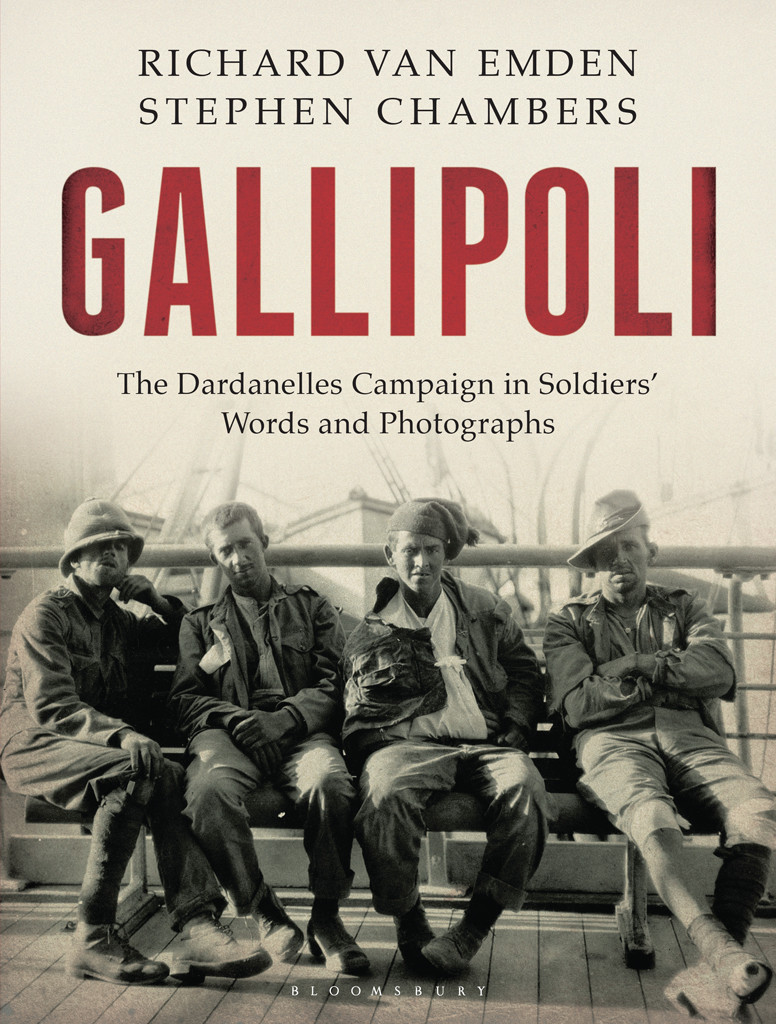

Of all the Great Wars campaigns and set-piece battles, those fought on the Western Front have remained uppermost in the public imagination: the Somme and Passchendaele, for example. Even Mons, that relative skirmish, is still a name to be reckoned with. Beyond the borders of France and Belgium, however, nothing is recalled with such alacrity as one name: Gallipoli. The campaign on the Anatolian Peninsula continues to enthral the imagination on both sides of the globe. In Australia and New Zealand, 25 April, the day of the first landings, is a national day of commemoration when both nations stop to remember with reverence the contribution of those who fell and those who fought and survived. It is a day more deeply embedded in the hearts of Australians and New Zealanders than Armistice Day, for 25 April has become inextricably entwined with both countries perception of national identity.

In Britain, the campaign is remembered as one of waste, yet fought with great heroism and in the teeth of impossible odds. Gallipoli is where tens of thousands of Allied men slugged it out with a tenacious Turkish foe. The drama of the campaign is undeniable, for the Allies were never more than a stones throw from the sea and, therefore, disaster. Here was a land baked dry by searing summer heat, and where water was in desperately short supply. Illness and disease were rife. But Gallipoli is also where a remarkable escape was concocted and brilliantly executed: and over the years the British have developed a penchant for great escapes. Gallipoli is also remembered as Winston Churchills brainchild and his greatest disaster. As First Lord of the Admiralty, he was in a position to pursue his restless ambition to attack elsewhere, away from the stalemate of the Western Front. Churchill was a wily politician and he was to have many fine hours, but this decidedly was not one of them, and the failure at Gallipoli haunted him for the rest of his life. His woeful lack of any strategic awareness in pushing for the campaign found him out, and a lesser man would have been finished on the wider political stage.