George L. Mosse Series in Modern European Cultural and Intellectual History

Series Editors

Steven E. Aschheim, Skye Doney, Mary Louise Roberts, and David J. Sorkin

Advisory Board

| Steven E. Aschheim | Hebrew University of Jerusalem |

| Ofer Ashkenazi | Hebrew University of Jerusalem |

| Annette Becker | Universit ParisNanterre |

| Skye Doney | University of WisconsinMadison |

| Dagmar Herzog | City University of New York |

| Ethan Katz | University of California, Berkeley |

| Anson Rabinbach | Princeton University |

| Mary Louise Roberts | University of WisconsinMadison |

| Joan Wallach Scott | Institute for Advanced Study |

| Moshe Sluhovsky | Hebrew University of Jerusalem |

| David J. Sorkin | Yale University |

| Anthony J. Steinhoff | Universit du Qubec Montral |

| John Tortorice | University of WisconsinMadison |

| Till van Rahden | Universit de Montral |

Publication of this book has been made possible, in part, through support from the George L. Mosse Program at the University of WisconsinMadison.

The University of Wisconsin Press

1930 Monroe Street, 3rd Floor

Madison, Wisconsin 53711-2059

uwpress.wisc.edu

3 Henrietta Street, Covent Garden

London WC2E 8LU, United Kingdom

eurospanbookstore.com

English translation and scholarly apparatus copyright 2018 by the Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System

All rights reserved. Except in the case of brief quotations embedded in critical articles and reviews, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, transmitted in any format or by any meansdigital, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwiseor conveyed via the Internet or a website without written permission of the University of Wisconsin Press. Rights inquiries should be directed to .

Printed in the United States of America

This book may be available in a digital edition.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Noack-Mosse, Eva, 19021990, author. | Doney, Skye, translator. | Ciplijauskait, Birut, translator.

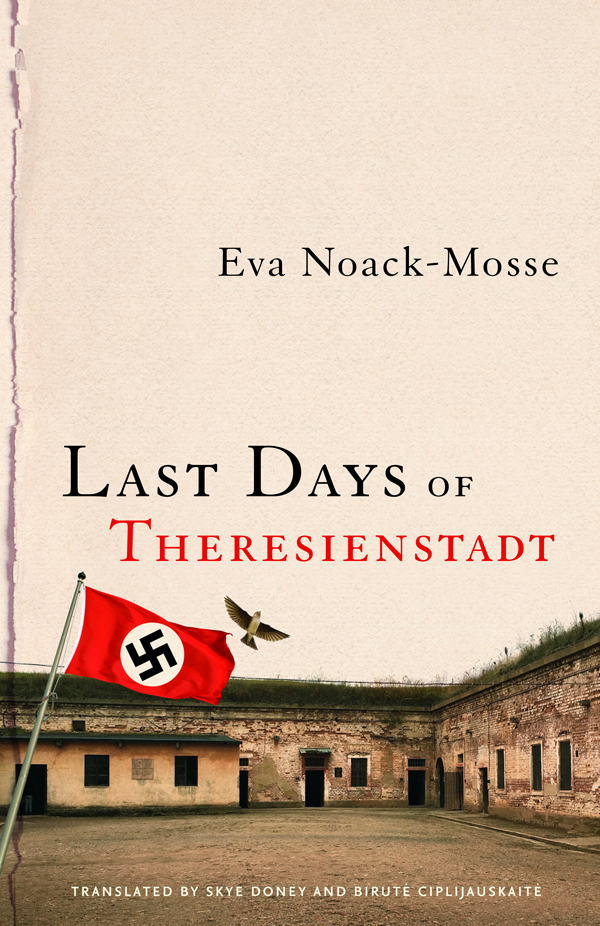

Title: Last days of Theresienstadt / Eva Noack-Mosse; translated by Skye Doney and Birut Ciplijauskait.

Other titles: George L. Mosse series in modern European cultural and intellectual history.

Description: Madison, Wisconsin: The University of Wisconsin Press, [2018] | Series: George L. Mosse series in modern European cultural and intellectual history | Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018013230 | ISBN 9780299319601 (cloth: alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Noack-Mosse, Eva, 19021990. | Theresienstadt (Concentration camp) | Women concentration camp inmatesCzech RepublicTerezn (steck kraj)Biography. | Concentration campsCzech RepublicTerezn (steck kraj) | World War, 19391945Concentration campsCzech RepublicTerezn (steck kraj)Personal narratives. | Holocaust, Jewish (19391945)Czech RepublicTerezn (steck kraj)Personal narratives. | LCGFT: Diaries.

Classification: LCC D805.5.T54 N63 2018 | DDC 940.53/1853716dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018013230

ISBN-13: 978-0-299-31968-7 (electronic)

Illustrations

Foreword

Mark Roseman

The decision to publish this edition of Eva Noack-Mosses Theresienstadt diary is a timely one. While a number of historians of womens experience in the Holocaust have made use of the German manuscript, currently available online from the Center for Jewish History in New York, an English translation has long been a desideratum. Noack-Mosses account offers us insights into a group that has still attracted far too little attention among scholars of Nazi Germany and the Holocaust, namely, Jews in what was in Nazi parlance a privileged mixed marriage. She also writes about a cluster of deportations that we still know very little aboutthe striking transfers of mixed-marriage Jews from the Reich into Theresienstadt in February 1945. She adds a new voice in describing that strange combination of concentration camp and ghetto that was Theresienstadt, new not least because she experienced such a distinctive phase of its existence. Her chronicle captures not only the last months of the ghettos life under Nazi rule but also the weeks after liberation. The account introduces us to a robust, courageous personality, one imbued with the virtues of acculturated and educated German Jewish women of the time but complemented by her own insight, humor, and charm, who offers an unforgettable portrait of strength and optimism in a time of enormous challenges. At the same time, Noack-Mosses diary is not always an easy source to interpret. Part of what makes it so interesting, in fact, is the intriguing question it raises about where to draw the dividing line between memoir and diary, a question of importance for approaching other Holocaust sources too.

Eva Mosse, who was thirty years old when the Nazis came to power, would undoubtedly have made strenuous efforts to leave Germany before the war (and would otherwise have been most unlikely to survive)had she not married a non-Jew, Moritz Noack, in 1934. The opening sections of this diary highlight the peculiar situation in which Jews in mixed marriages found themselves in Nazi Germany. The Nuremberg Laws of 1935 banned interracial marriage, but for various reasons the regime shrank back from targeting already married couples. As a result, and particularly after 1938, Jews in mixed marriages would find themselves protected from measures aimed at their fellow religionists (or those whose descent marked them in Nazi eyes as Jewish). At first sight, this protection is unexpected. There is nothing in Nazi antisemitic thinking that would lead one to think the regime would treat such couples leniently; indeed, one might expect the reverse, since the Nazis saw the greatest threat to Germany as emanating from Jews who had managed to insinuate themselves into Aryan society. But Hitler was also strategic. He was aware that in order to minimize the risk of reaction from non-Jews to anti-Jewish measures he had first to increase Jews isolation. A steady stream of regulations in the 1930s destroyed the basis for social, cultural, and increasingly also professional interaction between Jews and Gentiles. However, existing marriages remained one point of contact between Gentile and Jewish society that the regime hesitated to target directly (though in 1938, by legalizing divorce on racial grounds, it did make it easier for Aryans to discard their Jewish spouses).

This hesitation became very evident in the weeks after Kristallnacht, when new regulations allowed Jews to be forcibly removed from their apartments and concentrated in so-called Jew houses. Jews in mixed marriages, or at least privileged mixed marriages, defined as marriages where the male partner was non-Jewish or where there were children who counted as mixed race, were explicitly exempt from these regulations. Married to a non-Jewish man, Moritz, Eva Noack-Mosse thus counted as privileged. When, as she recounts, antisemitic neighbors sought to have her and Moritz evicted, her landlords had a clear legal basis on which to resist the pressure and in fact get rid of the complainants. In the massive expropriation of Jewish assets that took place in 1939, couples with a non-Jewish male partner were not as hard hit as others, since the husbands assets were not liable to confiscation. When the Jewish star was introduced in September 1941, the Jewish spouses inprivileged marriages were not forced to wear itwhich is why Noack-Mosse was so struck by having to wear one in Theresienstadt. Even Jews in the comparatively small number of mixed marriages not deemed to be privileged were generally excluded from deportationsthough they were exposed to most other anti-Jewish measures. By September 1944, more than 85 percent of the just over fourteen thousand Jews still living in Germany proper were intermarried.