For Hester, and for all children

There are stars that twinkle in the sky although they burned out long ago and people who bring light to the world although they are no longer with us their light shines especially bright in the darkness of night they show the way for us all Hannah Senesh (19211944)*

IN MEMORIAM Hans Krsa (18991944) was the composer of the childrens opera Brundibr , which was a light in the darkness for the children of Theresienstadt. It will always keep alive the memory of the children who were killed in the Holocaust and their hope for the victory of good over evil. Hana Epstein (Holubika)

Eva Fischl (Fika)

Ruth Gutmann

Irena Grnfeld

Marta Kende

Anna Lindt (Lenka)

Hana Lissau

Olga Lwy (Olile)

Zdenka Lwy

Ruth Meisl

Helena Mendl

Maria Mhlstein

Bohumila Polek (Milka)

Ruth Popper (Poppinka)

Ruth Schchter (Zajek)

Pavla Seiner

Alice Sittig (Didi)

Erika Strnsk

Jiinka Steiner

Emma Taub (Muka)

The Girls of Room 28 who did not survive

Da Bloch

Hana Brady

Petr Ginz

Jana Gintz

Harm Hachenburg

Eli Mhlstein

Pita Mhlstein

Honza Treichlinger and all the other murdered children of Theresienstadt

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

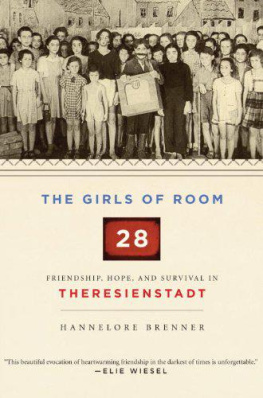

Anna Hanusov-Flachov and Helga Pollak Kinsky With the end of the war, those of us girls of Room 28 who had survived were scattered throughout the world; only a few of us were in contact in the decades following the Holocaust. We did not know what had become of most of our friends. It took almost half a century for us to find one another again. In October 1991, after the Berlin Wall came down, a few of us met in Prague for the first time since we had lost touch. We came from everywherefrom Israel, the United States, Russia, England, Sweden, Germany, Austria, and Czechoslovakia. It was an unforgettable moment. Gathered together in the lobby of an international hotel, we laughed and wept and spun in circles of joy as bystanders looked on in amazement. We were all surprised to find that our feelings had stayed the same as they were back then in the Girls Home in the Theresienstadt concentration camp. We felt like a family all over again and understood each other marvelously. Since that day we have been seeing one another regularly. Our great fortune at being together reminded us of all the girls and boys, caretakers, teachers, and doctors who did not survive, and we very much desired to rescue from oblivion those who had lost their lives in the German camps. That was the first impulse for this book. And then, in Prague, we became acquainted with Hannelore Brenner, and we were set to move ahead. We all agreed to meet at our favorite place, Spindlermhle, in the Giant Mountains. This book is the result.

CHAPTER ONE

Spindlermhle, Czech Republic, Autumn 2000

E very fall since the mid-1990s a group of extraordinary women gathers at Spindlermhle, a little Czech resort just below the headwaters of the Elbe, in the Giant Mountains. For a few days, the atmosphere in this small town is filled with the sounds of their joyous reunion, with songs and laughter, but also with the sad memories of their childhood, more than half a century ago.

The women are in their seventies, and they come from all parts of the globe. The shared vacation, which arose spontaneously out of their pleasure at having found one another again after so many years, quickly developed a momentum of its own, attracting more participants with each passing year. Soon the reunions became a cherished tradition. And while the women enjoy their time together, their hearts are both saddened by the approaching farewells and hopeful as they contemplate future reunions.

This annual meeting has come to represent the high point of their year. With bracing breezes blowing through its forests and the sparkling Elbe River rushing by, Spindlermhle radiates enchantment. The women feel rejuvenated as they hike up the mountains or stroll along the rushing stream. They bask in the happiness of being together. Their happiness is palpable to outsiders, who might well wonder what invisible tie binds them. The women themselves would offer a simple answer: We feel like sisters, like a family. Were happy when we are together.

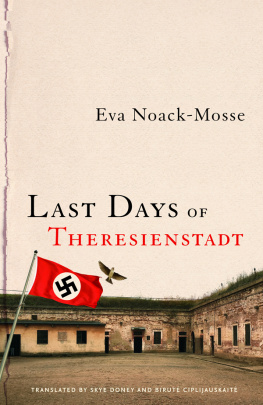

Indeed, the women are like sisters, bound by a special fate: Between 1942 and 1944, when they were twelve to fourteen years old, they lived in Room 28, Girls Home, L 410, Theresienstadt, a fortress town near Prague. They were prisoners of the ghetto, a small group of the 75,666 Jews from the so-called Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia who, with the incursion of German troops into their country, lost their homes, their property, and their freedom.

In Room 28, their paths crossed with those of about fifty other girls. They spent their lives, day and night, together in the closest of quarters thirty girls at any given time confined to approximately 325 square feet. They slept on narrow two-and three-bed wooden bunks, ate their meager rations together, and listened as their counselors read to them when evening fell. Once the lights were out, they would talk about their experiences and share their thoughts and dreams, their worries and their fears.

Time and again, some of the girls would suddenly be torn from their midst and forced to join one of the dreaded transports to the East. New girls would arrive in Room 28 and grow accustomed to this community that had been created by force. New friendships formed, only to be torn asunder again by the next transportsthe word itself a metaphor for the constant fear that dominated their daily lives. Under the increasing pressure of these threatening events, the girls would cling together all the more tightly. And then, in the fall of 1944, a devastating wave of transports carried off almost all the girls and boys, putting an end to the childrens homes and to Room 28.

It was at that time that Eva Fischl wrote in the album of her friend Flaka, as Anna Flach was lovingly nicknamed by her friends: When the day comes that you are back in Brno and you are eating a fish, remember that in Theresienstadt there was also a little fish. Your Eva Fischlov. Fiku. And with a few pencil strokes she added a picture of a fish. Little Ruth Schchter, whom everyone called Zajek (Rabbit), dedicated these words to her: Dont forget the girl who wrote this, and lovingly stuck by you. Your; and here she drew a mother rabbit with seven bunnies, followed by: Dear Flaka: Will you always remember who lay beside you? And was your good friend????????

At first glance, Anna Flachs little album isnt much different from the kind that many girls keep at that age. Here, too, one finds aphorisms like this one from Goethe: Relish your good moods, for they are rare. And dedications from friends and relatives: All the best for your future. Your Aunt Ella in Vienna. July 23, 1940. And a steady stream of pictures and sketches: colorful flowers, a squirrel, a girl peeking through a keyhole, a puppy, an idyllic village street. Only gradually does it dawn on us that this little book, with its crumbling yellowed pages, tells a totally different story from that of most other albums that survive solely for nostalgias sake, like my own. It is obvious that other powers kept this book alive. In it are the living memoirs of the murdered girls from Room 28 and the sorrow of their unfulfilled hopes and dreams. In Flakas imagination these youngsters live on as they were thenlovable, talented, full of fantasy, some calm and thoughtful, others athletic and vivacious. Flaka and her friends keep asking themselves: What would have become of them? Of Lenka, who wrote such wonderful poems? Of Fika, who came up with witty sketches and loved the stage? Of Helena, with her talent for drawing and painting? Of Maria, with her beautiful voice? Of Muka, Olile, Zdenka, Pavla, Hana, Poppinka, and sweet little Zajek, who was so helpless and in need of protection?

Next page