Lafayette seems to have spelled his name both La Fayette and Lafayette; the latter usage is, however, almost constant after 1789. The author has followed local usage, starting with La Fayette, then switching to the compound form after 1789, but always leaving the spelling uncorrected in all documents, memoirs, and letters quoted in the text.

The author has also respected Lafayettes spelling in English, along with his often faulty grammar and Gallicisms, except in rare cases where they obscured meaning. Whenever Lafayette wrote to an English-speaking correspondent, he used English; his letters to French recipients have been translated into English by the author.

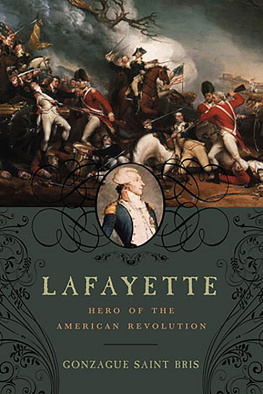

There was no need to mention his name, at first, in the United States: to all the Patriots, he was simply the Marquis, as if there had been no other on the surface of the earth; but soon they couldnt get enough of it. There were Lafayette streets, Lafayette counties, Fayettevilles . He was a hero, the Frenchman who came to fight for the United States, a man who neither feared danger nor sought advancement but selflessly gave of himself that the fledgling country might live, and offered so potent an example that soon all the might of France followed him.

As time passed, those feelings grew even stronger. When Gilbert Lafayette returned to the United States in 1824, he was greeted everywhere by wildly enthusiastic crowds and given a large grant of money and land by an otherwise parsimonious Congress. Then, almost a century later, when the United States went to the aid of France, there was the Lafayette Escadrille and General John Pershings famous (if probably apocryphal) Lafayette, we are here,

Today, still, Lafayettes name is taught to schoolchildren across the country as that of a man who loved liberty so truly and so well that he unselfishly dedicated himself to its cause. Of course, few wonder what happened to him after 1781: having helped bring about the victory at Yorktown, he returned home to France and the great epic was over. Except that the young Hero of Two Worlds, as the French called him, after being acclaimed almost as wildly in Paris as he had been on the other side of the Atlantic, lived on for fifty-three more years, during which time he helped dethrone two kings and an emperor. And while in America he is still an unsullied hero, in his own country , Lafayette is often considered a fool or a traitor or both.

Today, as in 1792, the French quickly judge a man by his political stance, and the political extremists often speak loudest. Although Lafayette in his old age claimed he had always been a republican , his opposition to the Jacobins and the abolition of the monarchy in 1792 still rankle among those who exalt Robespierres achievements; while to those who loathe the Revolution, either because they consider themselves part of the elite, or because, for them, history has stood still since Napoleon, Lafayette, much like Franklin D. Roosevelt in America in the 1930s, is considered a traitor to his class. Indeed, this curious attitude, adopted by Lafayettes own descendants through most of the nineteenth century, survives to this very day.

If one were to read most of the words published in France about Lafayette, one would have to conclude that this selfless genius was a popularity-mad fiend; that this steadiest of liberals was a nincompoop swayed by every political breeze; that this brilliant young leader was stupid, awkward, dull, and incompetent. Surely, then, Lafayette must have been a trial to his family and friends. In fact, nothing could be more wrong: T his unfaithful but loving husband, this kind father, this good and true friend was adored by all who knew him well. No one was ever happier or more cherished in his domestic circle, more willing to help the unfortunate, more respected by all those who loved liberty. When the people of France rose, in 1830, against a tyrannical king, they turned instantly to Lafayette: H e was a man they could trust, a man incapable of fraud and deceit, a man, finally, utterly devoid of personal ambition. And all over Europe, it was to Lafayette that the oppressed looked for help - Italian liberals, Spanish constitutionalists, Polish freedom fighters. All came to the man who stood uniquely for democracy and justice.

Surely, then, the reactionaries who mock him are wrong. But are they entirely so? For Lafayette is also the man who, during the French Revolution, constantly found himself doing things he disliked to retain his popularity; the man who, all through his life, demanded a return to the unworkable Constitution of 1791; the man, finally, who set up a new king, Louis Philippe, and a new rgime, only to denounce both, in bitterness and impotence.

In an age when both left and right tend toward an extreme view of the world, it is not surprising to see Lafayette either traduced or ignored: N o one likes a true liberal. Still, Lafayette is far more complex - and his positions were often far more ambiguous - than has been supposed. His successes, like his failures, are not without reference to our own situation. Perhaps we still have something to learn from the Hero of Two Worlds.

T he author wishes to express his gratitude to the New York Public Library, as always an incomparable help to research; to the Bibliothque Nationale, Paris; to the Archives Nationales, Paris; to the Archives du ministre des affaires trangres, Paris; and especially to Mme Chantal de Tourtier-Bonazzi, the curator in chief of the Archives Nationales for sharing her extensive knowledge of Lafayette documentation. He also owes thanks to Elisa Petrini for her painstaking and highly effective work in clarifying the manuscript.

Anyone interested in Lafayette must also acknowledge the immense contribution made by Louis R. Gottschalk in his volumes covering Lafayettes life from his birth to October 1789. His work remains a monument of thoroughness and scholarship.

The chateau of Chavaniac, with its round medieval towers crowned with pointed slate roofs and modern central wing pierced by wide windows, was a typical aristocratic dwelling: I t retained some parts of the fortress it had once been but was improved in the new, more comfortable style, which had been in vogue for a century and a half. Without being really grand - it had a few more than twenty rooms - or really glamorous, for its owners were far from rich, it accurately reflected the state of France in 1757: O lder parts coexisted, often uneasily, with modern thought. And much the way the building towered over the hamlet clustered near its moat, so did the aristocracy dominate the Third Estate, the nine-tenths of the nation that was neither clerical nor noble.

In many ways, though, Chavaniac was unusually primitive. The Auvergne in which it stood was one of the most backward, most isolated provinces in France. It was also sparsely populated, so the castle and its village seemed almost lost in the empty countryside. There were no paved roads going past it, just ruts that became impassable whenever it rained hard. There were no public monuments, no city gates, no prosperous houses, just a grouping of thatch-roofed huts surrounded by filth. No one cleaned up after the pigs and chickens, and their offal stank as soon as the weather got warm.