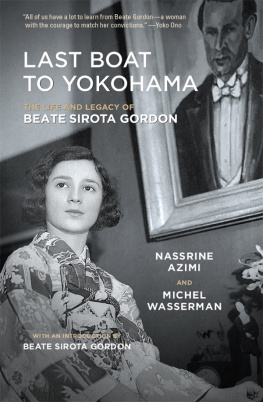

Last Boat

to Yokohama

THE LIFE AND LEGACY OF

BEATE SIROTA GORDON

Nassrine Azimi & Michel Wasserman

WITH A FOREWORD BY

BEATE SIROTA GORDON

THREE ROOMS PRESS

NEW YORK

Last Boat to Yokohama: The Life and Legacy of Beate Sirota Gordon

by Nassrine Azimi and Michel Wasserman

Copyright 2015 by Nassrine Azimi and Michel Wasserman

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. For permissions, please write to address below or email . Any members of education institutions wishing to photocopy or electronically reproduce part or all of the work for classroom use, or publishers who would like to obtain permission to include the work in an anthology, should send their inquiries to Three Rooms Press, 561 Hudson Street, #33, New York NY 10014

ISBN: 978-1-941110-19-5 (ebook)

Library of Congress Control Number: 2014951136

COVER AND INTERIOR DESIGN:

KG Design International

www.katgeorges.com

DISTRIBUTED BY:

PGW/Perseus

www.pgw.com

Three Rooms Press

New York, NY

www.threeroomspress.com

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

My gratitude to my mother Azar J. Azimi, for her love and gentle presence.

And to Chang Li Lin, Susan Dewhirst, and Kristin Newton, for their friendship and generous advice.

Nassrine Azimi

In Memoriam:

Joseph Gordon

(19192012)

and

Beate Sirota Gordon

(19232012)

Beate Sirota Gordon in the auditorium of the New York Asia Society (1987) (photo Mark Stern)

Foreword

by Beate Sirota Gordon

THIS BOOK IS ABOUT CROSS-CULTURAL EXCHANGE as my father, Leo Sirota, and I experienced it. It recounts my fathers work as one of the first European professors of piano at the Imperial Academy of Music in Tokyo (as it was called in the 1930s). It also recounts my own experiences as Performing Arts Director of Japan Society and Asia Society, bringing traditional, folk, and modern performing arts from Asia to the United States from 1960 to 1992. In between, it describes some of my experience and work as a member of General Douglas MacArthurs staff in post-war Japan, as a participant in the drafting of the Japanese constitution. I hope this book succeeds in conveying to future generations the imperatives of universal human rightsincluding and especially womens rightsand the transformative power of the arts to encourage our nobler instincts.

Leo Sirota was a child prodigy from Kiev who moved to Vienna to study with Ferruccio Busoni. Looking at newspaper clippings of that time, it seems as if he had played in every major city in Europe. It was a hectic schedule and often took him away from his wife and child. His move in 1929 to Japan, with its leisurely pace, was therefore a dramatic change from the European milieu he had known (and must have seemed in many respects like being in an oasis). He taught at the Imperial Academy of Tokyo and privately, as well as concertizing in the Far East. In Japan, his concerts were sold out, and his teaching schedule at the Academy and to private students at his home was full. He also performed extensively on radio. His name became legendary. He was a true cultural pioneer. When a student mentioned that he was going to perform in a small provincial town, and therefore wouldnt have to practice very much, my father replied that, on the contrary, he would have to practice so much that he could penetrate the ignorance of his rural public with his brilliant technique and deep feeling for the music.

I started out as a monitor of Tokyo radio broadcasts for the CBS Listening Post in San Francisco, in the summer of 1942. This turned into the Foreign Broadcast Intelligence Service of the Federal Communications Commission. I translated broadcasts from Japanese, German, French, Russian, and Spanish. In 1944, I joined the Office of War Information, as a writer and translator into Japanese of its propaganda broadcasts to Japan. In 1945, I moved to New York City and became an editorial researcher for TIME magazine. After the end of the war, in December 1945, I arrived in Japan to work as a research expert, for the Government Section of the GHQ SCAP (General Headquarters: Supreme Commander Allied Powers). I did research on women in politics and minor political parties, and worked on the political and economic purges, in addition to writing the womens rights article in the new Constitution of Japan. It was through my work in drafting the Constitution of Japan in 1946 that I first had the opportunity to introduce concepts from the West (though not necessarily from the United States) to Japan. I realized from reading so many constitutions how important it was to include human rights in this new constitution. In the nine days we worked on this document, we were exhilarated to be able to plant the seeds of democracy in Japan. I was thinking about the many Japanese women I knew, who did not have any rights at all under the old Meiji Constitution. I think most of the work we did then remains quite relevant today, as much for Japanese women as for women in other countries. I did my best to convince the Steering Committee to also include social welfare rights. I did not succeed. However, I did get approval for basic human rights.

I LEFT JAPAN FOR THE UNITED States in 1947 and married my coworker in GHQ, Lt. Joseph Gordon, in 1948. In 1954, I was named Education Director of Japan Society in New York City. Four years later, I became Japan Societys Director of Performing Arts. In 1970, I started working as Director of Performing Arts of Asia Society until I retired in 1991. Since 1995, I have been giving lectures on the constitution of Japan and on cultural exchange between Japan and the US. In 1997, my book The Only Woman in the Room was published.

What my father did parallels in some ways what I did later on in my career, but in the opposite direction. In his case, he brought West to East; in my case, I brought East to West. My late husband pointed out that this cultural exchange should not be too difficult a task, since all people have so much in common. We all have two hands and two feet, and one head. We all laugh at humor, we all cry when we are sad, we all want our children to succeed. In other words, we have many similarities to build on, and that was what we had to do. In my work I encountered many examples of the cultural similarities among different peoples. I was astounded when I saw martial arts exercises in Purulia, India, that I had learned as a student at the German School in Japan. I found a dance step similar to ballets bourre in Chinas Peking Opera. I found drums and flutes all over Asia, very much like their Western counterparts. At the beginning, I brought performing arts from Asia which were easy to communicate to a Western audience. I had excellent visual aids such as brochures, posters, and photographs, which helped in my efforts to make people appreciate the performance. But most importantly I brought the best performers who knew how to communicate their art. Of course, I also had difficulties, but fortunately I had learned from my father how to deal with such situationscalmly and patiently. Some performers wanted to bring flashy costumes to the US, thinking this would impress a Western audience. They feared that authenticity was too drab! It took a lot of persuading to convince them otherwise.

In the end, my husband was right. It is not that difficult to introduce one culture to another. But it can only be done by presenting the best of the alien culture, by explaining it and by demonstrating and highlighting that which we all have in common. My father did it, I did it.

Next page