A Pioneer

in Yokohama

A Dutchmans Adventures

in the New Treaty Port

C. T. A SSENDELFT DE C ONINGH

A Pioneer

in Yokohama

A Dutchmans Adventures

in the New Treaty Port

From Ontmoetingen ter Zee en te Land

Edited and Translated,

with an Introduction, by

M ARTHA C HAIKLIN

Hackett Publishing Company, Inc.

Indianapolis/Cambridge

Copyright 2012 by Hackett Publishing Company, Inc.

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

15 14 13 12 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

For further information, please address

Hackett Publishing Company, Inc.

P.O. Box 44937

Indianapolis, Indiana 46244-0937

www.hackettpublishing.com

Interior design by Elizabeth L. Wilson

Composition by Innodata-Isogen, Inc.

Printed at Data Reproductions Corporation

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Assendelft de Coningh, C. T. van (Cornelis Theodoor), 18211890.

[Ontmoetingen ter zee en te land. Volume 2. English]

A pioneer in Yokohama : a Dutchmans adventures in the new treaty port ; from Ontmoetingen ter zee en te land / C.T. Assendelft de Coningh ; edited and translated, with an introduction, by Martha Chaiklin.

p. cm.

Translation of 2nd volume of memoir entitled Ontmoetingen ter zee en te land [Adventures at sea and on land], published in 1879 by W.C. De Graaff, Haarlem, Netherlands.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-60384-836-7 (paper)ISBN 978-1-60384-837-4 (cloth)

1. Assendelft de Coningh, C. T. van (Cornelis Theodoor), 18211890. 2. DutchJapanYokohama-shiBiography. 3. MerchantsJapanYokohama-shiBiography. 4. Yokohama-shi (Japan)Biography. 5. Yokohama-shi (Japan)Description and travel. 6. Yokohama-shi (Japan)History19th century. 7. Yokohama-shi (Japan)Social life and customs19th century. 8. NetherlandsRelationsJapan. 9. JapanRelationsNetherlands. I. Chaiklin, Martha, 1960 II. Title.

DS897.Y69D82713 2012

952.1364031092dc23

[B] 2012020501

ePub ISBN: 978-1-60384-907-4

Although the author of this work had literary aspirations, its value to twenty-first century readers is historical. C. T. Assendelft de Coningh offers a unique account of a time period that is as fascinating as it is poorly documented. For this reason, I have kept the translation fairly literal. Place names and Japanese words are transcribed as in the original manuscript. Edo, the original name for Tokyo, is thus variously transcribed as Jeddo or Jedo. De Coningh, like many Dutch people, had a wide knowledge of other languages that he inserts frequently into the text; to turn all of the foreign phrases in his manuscript into English would alter his voice. English words in De Coninghs original manuscript are here shown in quotes. Likewise, De Coninghs footnotes are denoted with an asterisk, while mine are numbered.

I would like to take this opportunity to thank the many friends and some total strangers whose expertise I called on to untangle this idiosyncratic text:

First must be Marten Brienen because he called dibs on first. Simon J. Bytheway reassured me several times that this was a worthwhile project. In addition to Marten, many people answered my very odd questions out of pure altruism. These included John Lundstrom, Rudger van Dijk, Isabel van Daalen, Tim Couch, and Jeff Crowell. Other people assisted in various ways, including Margarita Winkel, James Hommes, Christopher Neander, and Tarik Allen. Some of the research was conducted with financial assistance from the Fulbright Foundation and the University of Pittsburgh. If Ive forgotten to thank anyone for their help with this project, I hope they will believe Ive done so only as a result of my poor record keeping and not because Im ungrateful. I am also indebted to Rick Todhunter, Christina Kowalewski, and everyone at Hackett Publishing Company for giving this project a home. Finally I wish to thank my parents, Harris and Sharon, my sons, Samuel and David, and my friends Laura Mitchell and Kerry Ward. You are my rocks in the typhoon of life.

Despite all this help, all the mistakes are mine and mine alone.

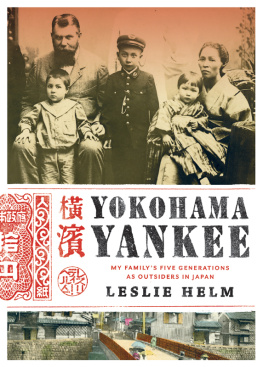

C. T. Assendelft de Coningh, ca. 1850. Courtesy of Reinoud van Assendelft de Coningh.

Threatened by the activities of Western missionaries, the Japanese military bureaucracy known as the Tokugawa Shogunate expelled all Westerners, save for the Dutch, from the country by 1639. The shogunateformed in 1603 after more than a century of civil war fought along quasi-feudal lineschose to impose this isolationism as a defense against a perceived conflict of loyalties engendered by conversions to Catholicism. To the Shogun, such demands for alliance with Rome conflicted with the oaths of allegiance Japanese warlords were required to make to the shogunate, and so threatened to undermine Japanese sovereignty and stability. Moreover, the conversion of various Japanese leaders to Christianity seemed to endanger the Shoguns hard-won political unity.

In the 215 years that followed, Japan remained closed to any overtures made by Western countries. But the Japanese tolerated employees of the Dutch East India Company because the Company was a secular institution more interested in making a profit than in spreading religious doctrine. Moreover, the Company had made a number of concessions to the Shogunate in order to establish a monopoly on direct trade with Japan. They agreed to reside only on Deshima (or as De Coningh spells it, Decima), a small artificial island in the harbor at Nagasaki; restrict the number of traders working in Japan; prohibit the presence of women and churches; and submit to the confiscation of any religious materials while in port. Even with their monopoly secured, however, the once promising Dutch trade with Japan eventually shrank to a mere trickle of money and goods.

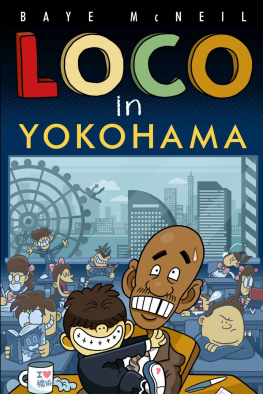

Then, in 1850, the United States governmentinspired by the doctrine of Manifest Destiny, effectively banned from China, and desiring trade (especially whaling) and trans-Pacific sea routesdecided to open Japan. Through gunboat diplomacy, Commodore Mathew Perry was able to extract from the shogunate a simple supply treaty, the Treaty of Kanagawa in 1854; American Consul Townsend Harris then negotiated the treaties that opened Japanese ports to free trade in 1859. Because the Dutch political stance was staunchly free market, their official representatives were actively employed as middlemen in negotiating terms between the Japanese and Americans, thus giving them a unique perspective on one of the most important events in world history. A unique middleman of a different sort, merchant and sea captain Cornelis Theodoor Assendelft de Coningh witnessed life in Japan both before and immediately after the opening and left us a vivid, detailed, and lively account of his time there.

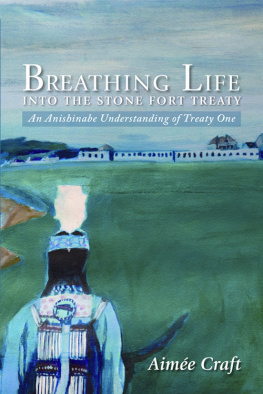

The Assendelft de Coningh coat of arms. The black eagle was from the De Coningh Family, the silver horse from the Assendelfts. Other maternal lineage was represented by the red star on gold ground (Van Carlingen) and crown over two salmon (Storm). This combined arms dates from the mid-eighteenth century. A. A. Vorsterman van Oijen, Stam- en wapenboek van aanzienlijke Nederlandsche familin, met genealogische en heraldische aanteekeningen, Part 1, plate 20. Image courtesy of Walter Andreas Groen.

Who was C. T. Assendelft de Coningh?

Cornelis Theodoor Assendelft de ConinghCees to his friendswas born in Arnhem, a city located in the East Netherlands, on March 5, 1821. He was probably named after his paternal grandmother, Cornelia Theodora van der Houven. Though most of the men in his family were merchants connected to both the Dutch East and West India Companies since at least the early eighteenth century, his father Arie served in the

Next page