To Nigel,

who has supported this project throughout

Contents

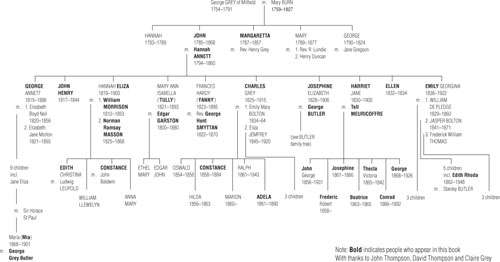

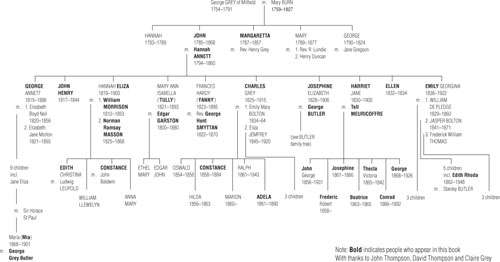

THE GREY FAMILY

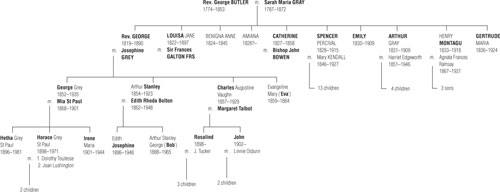

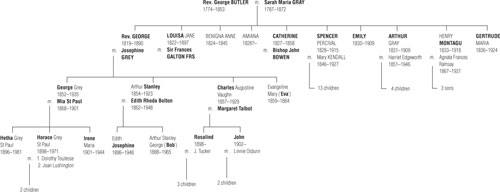

THE BUTLER FAMILY

I first heard about Josephine Butler when I was an undergraduate history student, and I began to research her writings in 1998 when I was a university teacher of religious and womens history. I was astonished by the power of her conviction and her personality, the range of her ambition and the extent of her achievements. I wanted to understand her, and I found that task to be long and complex so long, indeed, that I put it aside several times in order to complete other books. Since I started my research, other books about Josephine Butler have been published, and yet it remains true that her name is not well known to the British public but it should be. She was once described as the most distinguished Englishwoman of the nineteenth century. She was the leader of a national womens political campaign in Victorian England, at a time when women did not have the vote, and succeeded in repealing a law to which she and her followers strongly objected but which public opinion generally supported.

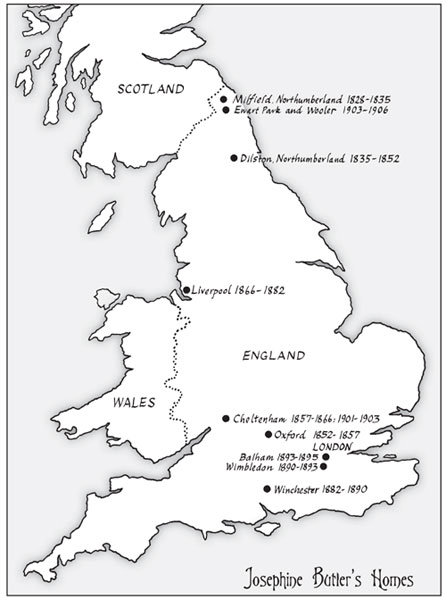

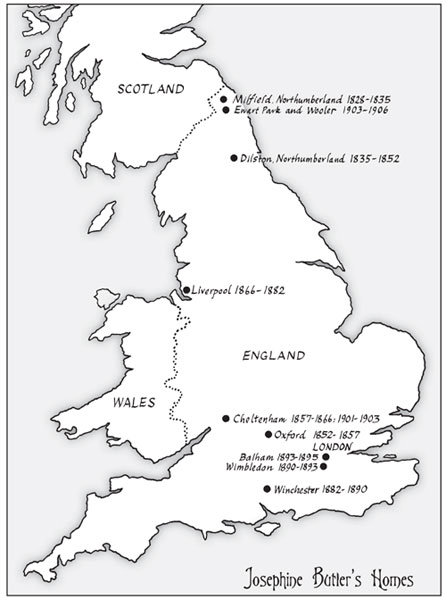

Josephine Butlers life spans the Victorian age born in 1828, she was 9 when Victoria came to the throne, and died five years after the Queen, in 1906. She was tall and beautiful, with thick lustrous hair which she wore long, in ringlets tied with ribbon or secured with a plait. She was slim, and always dressed with care, choosing tactile fabrics like lace and damask, set off by dramatic beads and earrings. She played the piano with true skill and sensitivity, and loved animals, especially dogs and horses. She came from a comfortable family home in the countryside, and was a devoted daughter and sister.

She was happily married to a husband who adored her and they had four children. But at the age of 40, Josephine became obsessed with the needs of women who were completely unlike herself. While living in Liverpool, she began to care for imprisoned and ill prostitutes, even inviting some to live in her own home. After the Contagious Diseases Acts were passed, which allowed these women to be sexually assaulted by police surgeons on a regular basis, she went into battle with Parliament, the police and the judges to change the law.

This battle consumed her home life, and undermined her physical and emotional health. Many times she collapsed and was confined to bed for weeks, but she kept the campaign going and secured the change in the law. The Ladies National Association for the Repeal of the Contagious Diseases Acts, which she led, was the first national womens organisation to score such a triumph in England. After this triumph she did not retire, but until the end of her life carried on trying to help abused women.

Why is Josephine Butler not as famous as Victorian heroines like Florence Nightingale? She achieved as much as Nightingale, probably more. But she was never celebrated by her country, never became a national heroine. Indeed, to many she was the reverse of a heroine, because she fought for womens rights, at a time when (with the single exception of Queen Victoria) men had all the power. Even worse, she fought for fallen women, who were regarded as subhuman by polite society. Prostitutes, she was told, were a class of sinners whom she had better have left to themselves since they were the authors of their own destruction. Josephine Butler never gave up, never backed down and forced society to face the sordid details of the abuse she was fighting. No wonder she was unpopular. Some of that rejection, that unpopularity, seems to have clung to her memory ever since.

This book aims to explain Josephine Butlers complex personality, motivated as she was by both feminism and her deep Evangelical Christian faith. The best way to understand this is through an account of her life and her relationships with her family, her supporters and her God. As a professional historian, I have sought to contextualise her campaigns with Interludes between the chapters explaining the historical background. Other Interludes explore her most important writings.

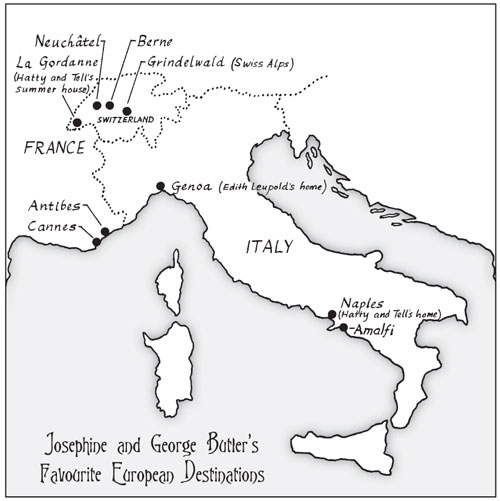

Josephine Butlers dramatic life story is far more sexually graphic than any Victorian novel. She went into brothels, prisons and the lock hospitals where women were examined and treated against their will. She stood up to cruel and coldly calculating authority figures such as the Superintendent of the Morals Police in Paris, the Minister of Justice in Rome and the Public Prosecutor in Brussels. It is also a great love story the marriage of Josephine and George Butler was blissfully happy and an invaluable source of support to her.

She chose a life which was a crucifixion is the verdict of one contemporary. Yet her achievements had lasting impact. Her name deserves to be remembered by all who value womens struggles to improve their lives.

PROLOGUE

T he following story, in her own words, illustrates Josephine Butlers character. In 1872 she and her friends were trying to stop the election of a candidate they detested, a man who supported the ill-treatment of prostitutes and had pimps among his supporters. The scene of this tense by-election was Pontefract in West Yorkshire, where large crowds had gathered and passions had been roused on both sides by fervent speeches. The fact that women were among the campaigners enraged men who thought they had no business becoming involved. The welfare of prostitutes was, in any case, a topic which respectable women should never speak about.

Josephine was undaunted by this, and indeed determined to find as many public platforms as possible. She decided to stage a parallel meeting to that of the candidate she opposed, Mr Childers:

On a certain afternoon, when Mr Childers was again to address a large meeting from the window of a house, I and my lady friends determined to hold a meeting at the same hour, thinking we should be unmolested. We had to go all over the town before we found someone bold enough to let us a place to meet in. At last we found a kind of large hayloft over an empty room on the outskirts of the town. You could only ascend to it by means of a kind of ladder, leading through a trapdoor in the floor. However, the place was large enough to hold a good meeting, and was soon filled.

the women were listening to our words with increasing determination never to forsake the good cause, when a smell of burning was perceived, smoke began to curl up through the floor, and a threatening noise was heard below at the door. The bundles of straw beneath had been set on fire

Then, to our horror, looking down the room to the trap-door entrance, we saw appearing head after head of men with countenances full of fury; man after man came in, until they crowded the place. There was no possible exit for us, the windows being too high above the ground, and we women were gathered into one end of the room like a flock of sheep surrounded by wolves

Since the women were trapped, all they could do was stand firm in the face of the shouting, swearing thugs who were advancing on them. Some were obviously pimps. Josephine and her friend Charlotte Wilson were their targets:

Next page