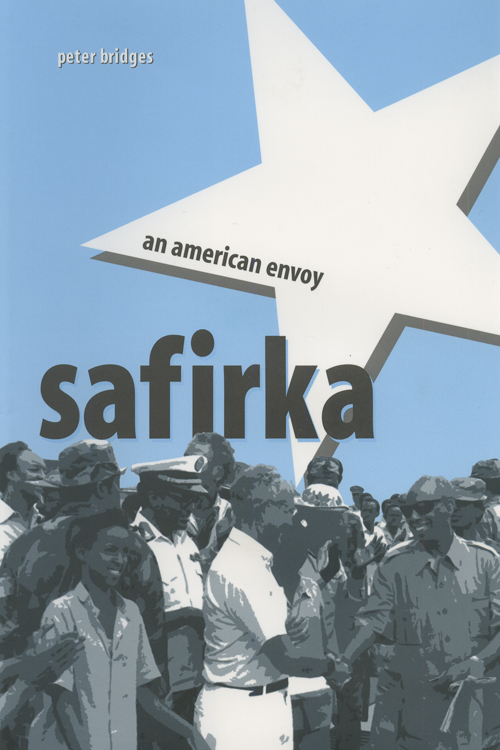

safirka

An American Envoy

Peter Bridges

The Kent State University Press

Kent, Ohio, and London

2000 by The Kent State University Press, Kent, Ohio 44242

All rights reserved

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 99-055501

ISBN 0-87338-658-2

Manufactured in the United States of America

06 05 04 03 02 01 00 5 4 3 2 1

Portions of this work appeared in slightly different form in Diplomacy & Statecraft (9:2, July 1998), Michigan Quarterly Review (37:1, Winter 1998), and the Virginia Quarterly Review (73:3, Summer 1997; 76:1, Winter 2000).

The lines by Andrew Marvell are from Upon Appleton House, reprinted in Andrew Marvell: Selected Poems, ed. Fred Marnau (London: Grey Walls Press, 1948).

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Bridges, Peter, 1932

Safirka: an American envoy / Peter Bridges.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-87338-658-2 (cloth: alk. paper)

1. Bridges, Peter, 1932 2. AmbassadorsUnited StatesBiography.

3. AmbassadorsSomaliaBiography. 4. United StatesForeign relationsSomalia. 5. SomaliaForeign relationsUnited States. 6. SomaliaPolitics and government1960-1991. I. Title.

E840.8.B75 A3 2000

327.730092dc21

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication are available.

This book is dedicated to my fellow travelers

Mary Jane, David, Elizabeth, Mary, and Andrew.

SafirAmbassador

SafirkaThe Ambassador

Waxaan ahay safirka mareykankaI am the American Ambassador

Somali phrase book

Why should, of all things, man, unruld,

Such unproportioned dwellings build?

The beasts are by their denns exprest,

And birds contrive an equal nest;

The low-roofd tortoises do dwell

In cases fit of tortoise-shell:

No creature loves an empty space;

Their bodies measure out their place.

But he, superfluously spread,

Demands more room alive than dead.

Andrew Marvell

contents

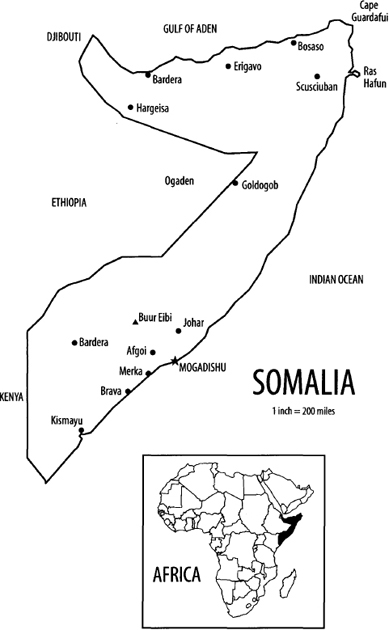

In spite of the tragic recent history of Somalia, there is a dearth of books about that country and its people. The horrors of the Somali civil war were extensively covered, at least as long as they continued, by world media. The massive intervention by the United States and by the United Nations in the early 1990s has been described in several published works. But what happened before that in Somalia? What comes next in a Somalia that heads the list of failed states? The country has fallen out of the headlines, but its millions of likable and intelligent humans still wantand deservea decent place in the world. Can they have any hope of this in a region still prey to strife and famine?

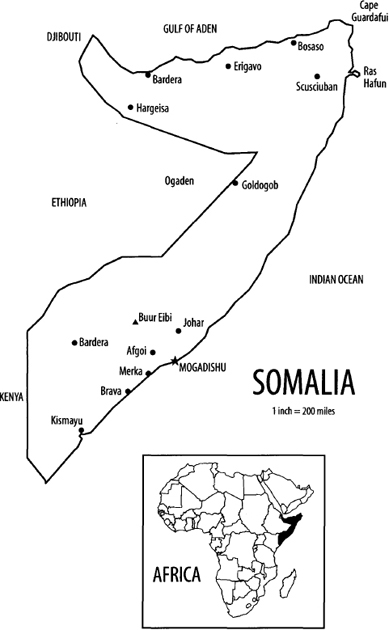

This book recounts my experiences as a career officer of the American Foreign Service, as ambassador to Somalia in 1984-86 and during the years before I went to Africa. Our Foreign Service includes many experienced Africanists, but I was not one of these; I was experienced in diplomacy, but before I went to Mogadishu I had traveled only briefly in Africa. What follows, then, does not claim to be the commentary of a lifelong expert on Africa but simply an objective account by a man who came to love Somalia, but not its dictatorial president; who studied carefully that countrys long and fascinating past and its appalling present; who did what he thought right both for American interests and for Somalia, sometimes on instructions from Washington and sometimes without them.

I have tried to avoid a dry, diplomatic account. I want to convey to readers what it is like to spend three decades in the Foreign Service: what it is like to be a young vice consul in Panama, a political officer in Moscow, a senior officer in Washington, an ambassador in Africa. It is not just what you tell the countrys president but what you think to yourself; it is not just what you report to Washington but what your senses tell you as you run along a Somali beach at glorious dawnor when you see emaciated infants dying in a dusty refugee camp. This ambassador got out of Somalia before its final collapse, but as long as he lives the tragedy and beauty of that country will stay with him, and so will the question whether America might have pursued a better policy in Somalia and elsewhere in postcolonial Africa. The horrors of Somalias civil war and the problems of Americas African policy are the subjects, almost inevitably, of the concluding part of this book.

There is a Somali proverb that goes, Run iyo ilkaba waa la caddeeyaa. In English, that would be Both truth and teeth get polished. Readers may decide for themselves whether polishing was applied to the facts that follow.

It was May in Rome, a pleasant season. I sat in my office in the Palazzo Margherita, an oversized, high-ceilinged room that had once been a queen mothers bedroom. I wished that it were Sunday and that my wife and I were making our way toward the top of some mountain in the Apennines, Monte Semprevisa, perhaps, or Monte Gennaro. The intercom buzzed, and my secretarythat marvelous lady from Boston, Maria Lo Contesaid that I had a call from Robert Oakley in Washington. Bob Oakley was our ambassador to Somalia; he was in Washington, I knew, for a few days consultation. We had agreed by cable that on his way eastward back to Mogadishu he would stop in Rome for lunch with people from the Italian foreign ministry. We and the Italians both had major interests in Somalia. Our interest was largely strategic, a result of the Cold War. Theirs was in good part historical; much of Somalia had been an Italian colony. We were both major donors of aid to Somalia, and we often compared notes on aid and other questions. I had done so as a political officer in the Rome embassy in the late 1960s, and I did so now as the number-two in that embassy, together with Bob Oakley whenever he passed through Rome.

Oakley was calling to say that he was going to be a few days late leaving Washington. He wondered if I could put off for a week the date for our luncheonand of course I could. Oakley went on to say that he would soon be leaving his post. He was being transferred back to Washington, where he was to head the State Departments Office for Combating Terrorism. A big, hard job, I said; congratulations. Whos going to replace you in Somalia?

I dont think theyve given that any thought yet, he said. Why, would you be interested?

My question had come from simple curiosity, and I had not expected his question in return. I thought for a minute. Yes, I said, Id be interested.

Good, said Oakley. Let me just tell a couple of people here. See you soon.

He hung up, and after a bit Maria came in and found me staring out the window. Spring fever, Peter? she asked. Not quite. What had I put myself in for?

The year was 1984, and my wife and I had been in Romeour second time therefor two and a half years. I was the deputy chief of mission (DCM in Foreign Service lingo) in the big Rome embassy, with the diplomatic title of minister. It was the biggest overseas job, and the most interesting, that I had had in twenty-seven years as a Foreign Service officer. An American television network had recently made a film, called The Deputy, that was supposed to be about the DCM in Rome. I laughed when I saw it. It showed correctly that we had a magnificent embassybefore the United States bought it (for a bargain price), our office building had been the palace of Italys Queen Mother, Margherita. But the TV film did not begin to convey what the DCM did to earn his pay.