Contents

Guide

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

To my family

And in memory of my parents and grandparents

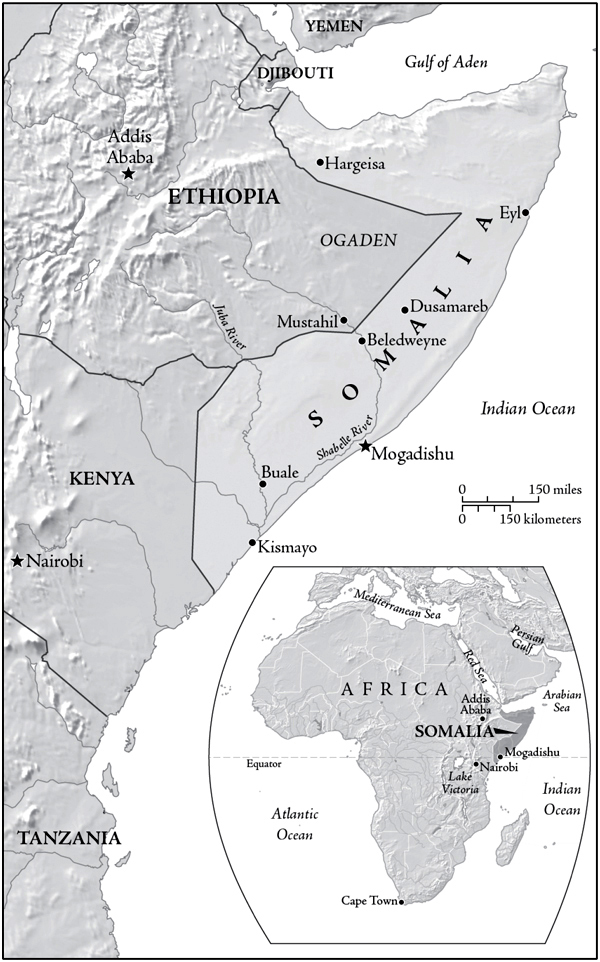

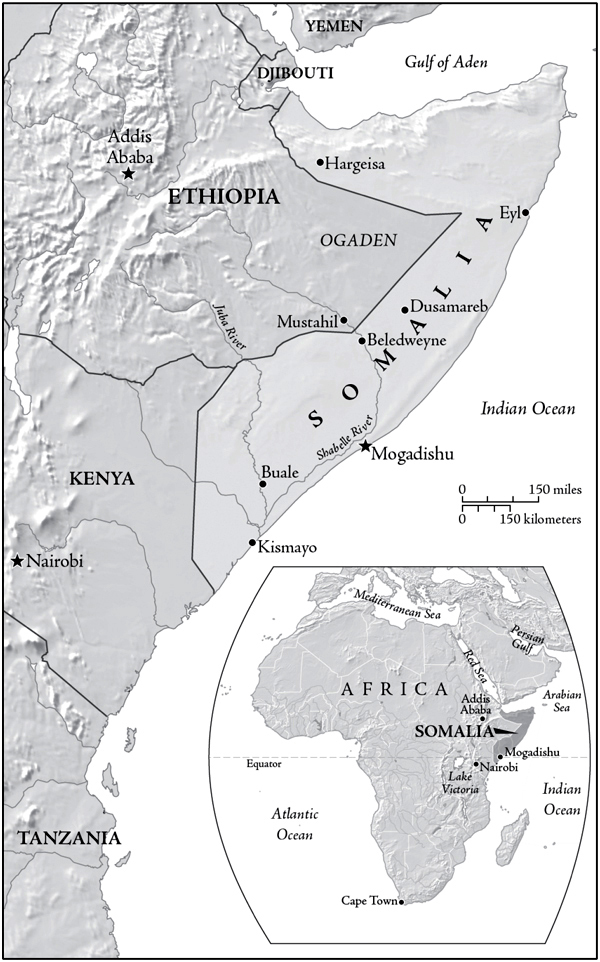

Map of Africa and Somalia. MAP BY PAUL PUGLIESE

Were safe in here. Surely.

MOHAMUD TARZAN NUR

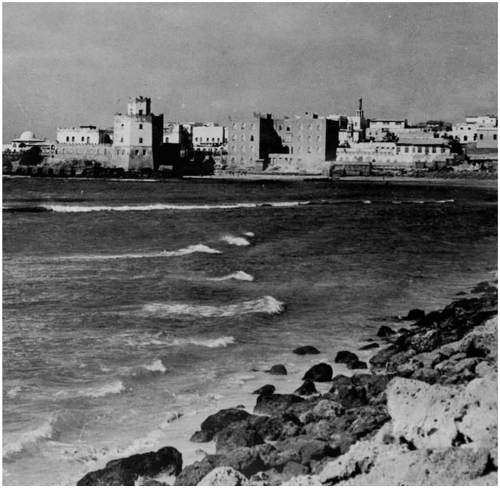

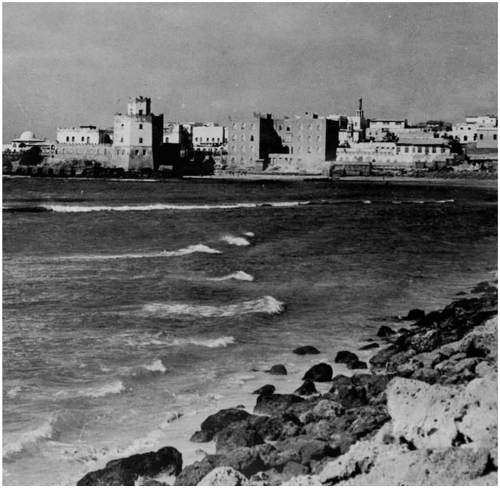

Mogadishu, 1960s. OFFICIAL MOGADISHU GUIDEBOOK, 1971

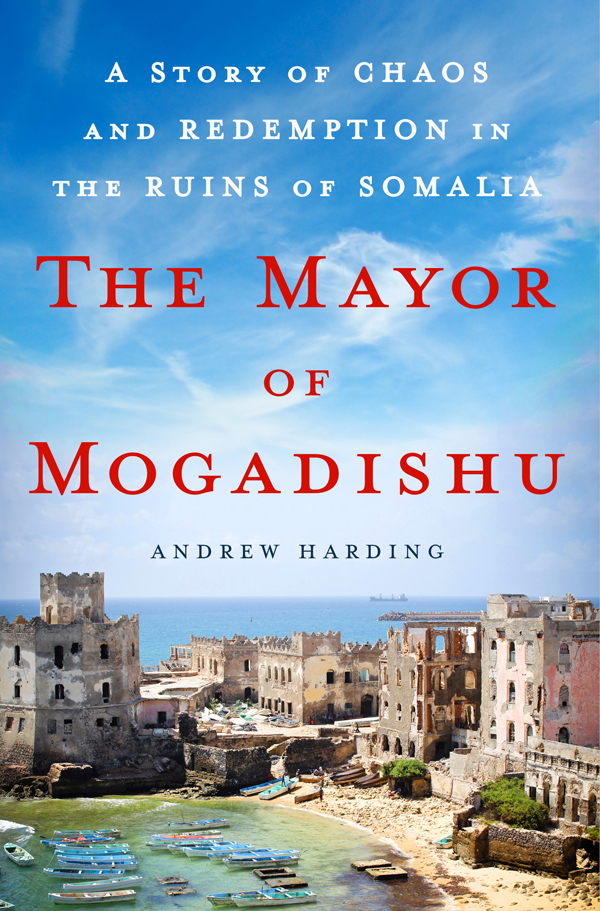

I MAGINE, FOR A MOMENT, THAT youre floating in the cold silence of space, somewhere over the equator, perhaps five thousand miles above the earth. From this height you can see the whole of Africa spread out below you. Pale yellow at the top and bottom. A stripe of avocado green across the middle.

At first glance, the continent resembles nothing in particular.

But if you tilt your head to the right, the shapeless lump below is suddenly transformed into an elegant horses head, leaning in from the left, and bowing down in a docile manner to sip the waters of the Antarctic Ocean.

The dark blotch of Lake Victoria is the horses right eye. Cape Town sits placidly on the bottom lip, and the place were interested inthe place were now racing towardis the horses perky right ear as it juts out and up into the Indian Ocean. From this height the ear, better known as the Horn of Africa, looks almost pink.

As we slip down, a thousand miles above the earth now, we glide toward the northeast, over Mount Kenya and Mount Kilimanjarofrom this height, just white pimples in the savannah. A straight, white coastline appears on the right.

Were over Somalia. Green patches in the south, then a vast, smudged expanse of grays and curdled yellows, with pink and red dabs, and the tiniest veins of dark green.

Now Mogadishu is directly beneath us. Somalias capital is just a dull smear on the coastline from this height. But were sinking faster, and swinging out over the bright blue water to approach the city like the commercial airlines still dokeeping away from the shore until the very last minute to avoid rockets and gunfire.

And then suddenly the city takes shape before us in three dimensions.

The name itself seems forbidding. Like Stalingrad, Kabul, Grozny, and, these days, Syrias Homs, Mogadishu conjures up lurid images of destruction.

But Mogadishu covers even more territory. It has become a bloated clich, not just of war but of famine and piracy, terrorism, warlords, anarchy, exodus All the worst headlines of our time invoked by one lilting, gently poetic, four-syllable word.

And yet today, as we swoop down toward the city center, Mogadishu looks unexpectedly, impossibly, undeniably pretty. A sandy, sunny seaside picture postcard of a city perched on a hill beside a turquoise sea.

Two curving harbor walls reach out into the Indian Ocean like crab claws. The airport runway emerges from the gruff, white waves to the south, to point like a guidebooks arrow toward the citys heart. Theres the beautiful old stone lighthouse, the outline of the cathedral, the fish market and a cluster of handsome old buildings around it, then a handful of taller buildings halfway up a gentle, dune-like hill, and the parliament at the top. And theres Lido beach further north, almost at low tide now, and starting to fill up with young bathers, some just visible either in groups on the sand or leaping into the surf in bright orange lifejackets, rented from tiny stalls on the rocky shoreline.

At first, its hard to see the ruins. The cathedral, for example, seems determined to hide the fact that its just a roofless shell, one of its twin towers missing. But as we glide inland and up toward the parliament, the rest of the city, tucked behind the first ridge like a guilty secret, comes into view.

The land dips behind the parliament, and we can see a makeshift camp of ragged tents, and beyond it, the slump of a shallow valley where the buildings seem to huddle before rising again toward the Bakara market. An experienced eye might notice the absence of greenery. Where are the trees that once shaded so many streets in this neighborhood? And here, in the middle of the slump, the fierce sunlight ripples sharply along a jagged line of rooftops. Its another clue. Like a bandage on a healing wound, the shiny corrugated iron roofs are evidence of the repair work now underway, as families try to move back into the ruins of what was, until recently, Mogadishus frontlinea scar that split the city in two.

This aerial view is appropriately perplexing. These are edgy, beguiling, bewildering times for Mogadishu, and indeed for the entire country. There is smug talk of corners being turned, signs of a failed nation clawing its way back toward viability, of the diaspora returning after decades in exile, businesses thriving, and stereotypes being shattered. Perhaps the worst is finally over. And if Somalia can breed optimism, what lessons might it hold for those now trying to fix Syria, Iraq, Yemen, and other broken states?

And yet below us, on the dusty streets of Mogadishu, the same beasts still prowl. Terror, corruption, clan conflict, extremism, and, chasing at their tails, the lingering fear that Somalia is merely flirting with stability. That it will soon slide back into old habits. That the only lesson it can teach us is what not to do.

Its almost exactly noon on a hot, cloudless Friday. And suddenly our attention is jerked away from that sunlit line of corrugated roofs. On what now looks like the highest point in the whole city, a large cloud of black smoke is rising like a balloon into the humid air.

It is Friday, February 21, 2014, and in a country where the percussion of violencegunshots, rockets, mortars, grenades, bombshas, over the decades, become embedded in peoples minds as the background music of an ordinary day, a particularly loud and brazen attack is beginning.

* * *

A DEEP, SHARP, BOOM rolls across the contours of the city.

A car bomb has just been detonated by a suicide attacker outside the half-renovated northern gate of Villa Somalia, the hilltop seat of the countrys government. Seconds later, a second car explodes nearby. The echoes of the two blasts mingle and separate, like thunder, across Mogadishu.

The explosions have entirely shredded two cars and torn a hole in the compounds wall below a new, half-built watchtower. Seven gunmen, dressed to look more or less like the official security guards patrolling the area, are rushing inside.

Villa Somalia is a fortress. But the attackers surely have inside knowledge. Theyve picked a weak point. At first they meet no resistance as they run up a wide, empty avenue along the outer wall of a house now occupied by Somalias new president.

Ahead of them, other large buildings are half-hidden behind trees. Theres the prime ministers residence, and the speaker of parliaments. Villa Somalia is an odditya swaggering Italian colonial palace, now caught somewhere between a luxury gated compound and a dilapidated college campus. It is home to the latest in a succession of fragile new Somali governments, some of whose authority has extended no further than the walls of Villa Somalia itself.