DEDICATION

Alice Ann (Rozelle) Hough

1939-2010

For my late sister, Alice Ann, who suffered more, forgave the most, and gave to her own children a parents love she herself had never known.

Table of Contents

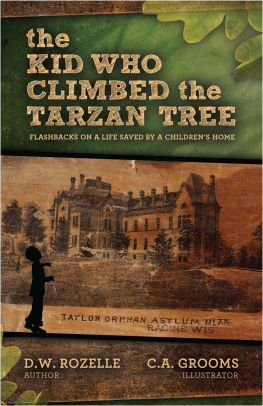

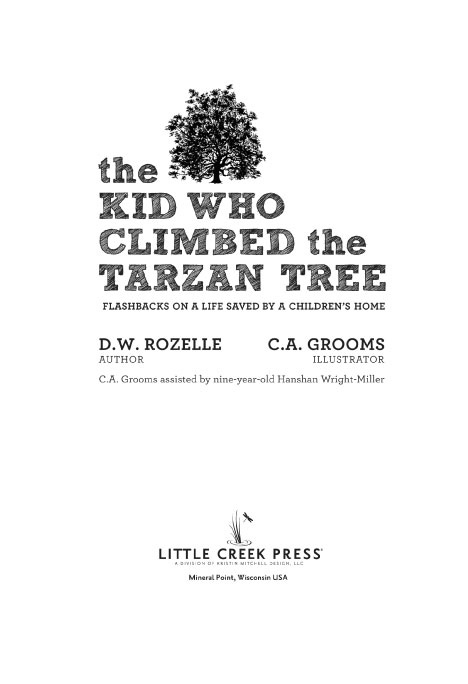

O n July 6, 1944, at ages six and five respectively, David and Alice Rozelle were placed at Taylor Childrens Home in Racine, Wisconsin. Their mother, Dorothy Rozelle, had contracted tuberculosis, necessitating her confinement in a Milwaukee-area sanitarium.

Initially the intent had been to return the children to their mothers care following her recovery. But following her release from Muirdale Sanitarium in 1945, Dorothys predisposition to emotional instability, alcohol abuse and joblessness quickened. Her former husband, Chester Rozelle, had retreated from family involvement following the couples divorce in 1941. By 1942 he had disappeared as a presence in the lives of his children.

As a result, Taylor Home became the Rozelle childrens caretaker until September 1, 1949, when they were relocated to a foster home in rural Racine County, Wisconsin. This is David Rozelles memoir of his nearly six years as a kid from the Home. It is also his belated tribute to the progressive philosophy and humane staff of the now-vanished Taylor Childrens Home.

The only reason for time is so that everything doesnt happen at once.

Albert Einstein

In which lost children, long dead, play in the ruins of their Home.

Dedicated with ceremony in 1872, demolished with none in 1972, Taylor Orphan Asylum disappeared without a trace of historical reverence or regret. Its fate has become an all too familiar spectacle of our time: todays bulldozers wantonly pulverizing yesterdays progress.

So it was for this century-old progressive sanctuary for children. The reforms of its past were ground into the debris of our presentout of sight, out of mind and, ultimately, out of memory.

The history of Taylor Homeas those of us who lived there called it in the 1940scries out for its emulation, not liquidation. During its one hundred years of existence, the Homes principles and practices gave enlightened refuge to scores and scores of indigent boys and girls, among them the author of this book.

The building itself stood like a magical Arthurian fortress on acres of beautiful Wisconsin countryside just south of Racine, Wisconsin. Its yellow brick, neo-Gothic exterior climbed three stories high, tall arched windows casting huge swaths of natural light into over eighty rooms.

At the very least, Taylor Orphan Asylum deserved historic preservation as a monument to its selfless founders, Isaac and Emmerline Taylor. Thanks to the bold beneficence of this nineteenth century childless couple, hundreds of downtrodden children found validation in the home these two had endowed with not only their wealth but also the humane bylaws they prescribed as its talisman.

But there is no monument. There is only a vanishing vision to be conjureda vision of ghostly throngs of boys and girls playing among broken bricks and shattered glass within rooms without walls or ceilings, deliverance or song.

JULY 6, 1944

In which my mouth drops at my first sight of the Home.

On that day, my first sight of it astonished me. Racines busy Taylor Avenue, a major thoroughfare, abruptly yielded to a road flanked by country pathways leading to nowhere, as far as I could tell.

And immediately there it was, visible through the car window to my left, set back to the east among aging oak treesan ornate edifice of Victorian architecture worthy of a prince and his Snow White. We had crossed an invisible borderline dividing Racines urban from its pastoral, dividing my present from my future. There it was. Taylor Orphan Asylum.

Gargantuan, constructed from pyramids of cream-colored bricks, it sprawled in nineteenth century Baroque splendor. It ascended three gracious Gothic stories with stately windows tall and arched, a stained-glass chapel snug against its north walls, and high, stone chimneys amidst pointed dormers rising from higgledy-piggledy mansard roofs. Magnificent.

And in photograph and memory, it still strikes me as magnificent: a rooted refuge fit for the happy childhoods denied to both 19th century English orphan Isaac Taylor and his more illustrious contemporary in childhood deprivation, the author Charles Dickens.

It was to be my home for nearly six years. It was a sunny summers morning, July 6, 1944.

In which a Kentucky belle and her English orphan husband imagine an asylum for luckless children.

They had turned out in portrait, in their best attire, to welcome me as, at six years of age, I stepped for the first time into the grand reception hall of Taylor Childrens Home. I undoubtedly gazed upward in bewilderment at the stolid likenesses of these rosy-cheeked personages, serenely attired in the black formal wear of their time.

The gazes of these twoIsaac and Emmerline Taylor, founders of Taylor Orphan Asylumwere decidedly not directed at me, but toward each other. Their half-length portraits, painted in rich oils and framed in gold, hung on opposite walls, directly across from each other in an entrance hall that spoke silently of their benevolence.

Isaac Taylor, born in 1810 in Englands Yorkshire County, had known firsthand the plight of children in hard times. Orphaned at an early age, he had been marked by the harshness of a childhood in an English poorhouse. Released at last at age eighteen he worked his way to America in 1828, making his way to Cleveland, Ohio, where he first exhibited the unusual coupling of a Midas touch with a heart of gold.

Taylor worked and scraped to buy a horse or two, and soon became a prospering livery keeper in Cleveland. In the meantime his heart had won the heart of young Emmerline Martin. They married in 1835.

The marriage produced children. But in an ironic reversal of the misfortune of Isaacs childhood, the Taylor children died before their parents.

In 1842undoubtedly sensing opportunity and perhaps in flight from the pain of the death of their childrenthey moved to Racine, Wisconsin, a small but growing port city on the western shore of Lake Michigan. There, Emmerline set up household, while Isaac headed north along the lake to Manitowoc County, where he invested in pine lands, saw mills, and real estate before returning to Racine. Midas had become a Wisconsin lumber baron.

The fortune which the threadbare Yorkshire orphan amassed in America was enormous for its time. His and his wifes worth at the time of his death amounted to half a million dollars.

During the short months before Isaac Taylors death, with the knowledge that both he and Emmerline were gravely ill, they discussed the disposition of their wealth.

Isaac died in 1865. During the few months remaining in her life, Emmerline formulated a will that embodied her late husbands desire to found an orphanage. Emmerline died in 1866. The Taylors left no heirs apparent.

Apparent now, howeverone hundred and fifty years after their deathsis that the beneficiaries of the Taylors last will and testament were multitudes of children in the direst straits. I am one. We are the heirs of Emmerline and Isaac Taylor, founders of Taylor Orphan Asylum.