Miscellaneous illustrations appear throughout the book, along with a photo gallery.

Preface

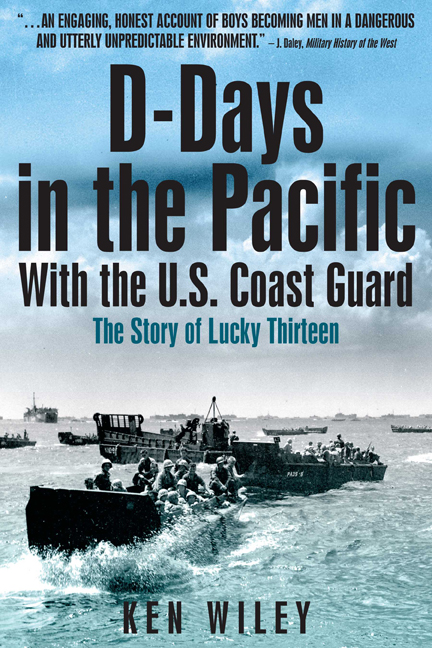

The Last Seven Miles

This story is about the U.S. Coast Guards role in World War II, as told from the perspective of a teenage boy who played a part in that great global struggle. It is also about an unheralded boat that played an insignificant and yet very important role in Americas response to restoring freedom to a part of the world enslaved by an evil tyranny. Lucky 13my boatwas a weapon specifically designed and mass produced in the United States to bridge the 6,000-mile ocean gap and carry the war to the shores of the enemy. The Higgins boats were lowered from troop ships with one mission: to carry the infantry and equipment the last seven miles of the long and perilous journey onto the beaches of enemy-held islands.

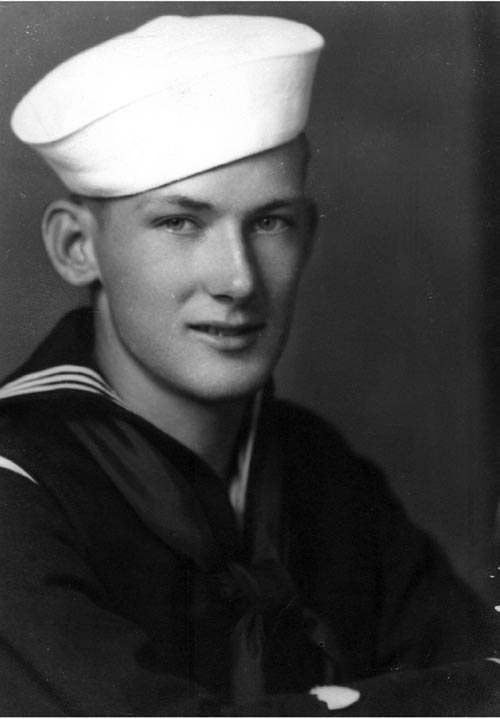

I grew up in the U.S. Coast Guard. Although I was only a kid of seventeen when I enlisted, I was a man when I left the service at twenty. You grew up quick in those days and under the circumstances so many of us experienced. I spent six short weeks in Boot Camp in St Augustine, Florida, where I saw my first ocean; nine weeks in Landing Craft School with the Marines at Camp Lejuene, North Carolina, where I saw and was given my first landing craft and on to a waiting Attack Transport, and where I was hoisted aboard my first ship as a Coxn of an LCVP (Higgins boat). Six months after I joined the Coast Guard I was heading for Kwajalien in the Marshall Islandsmy first invasion in the Pacific theater of war.

I was one of five brothers who served in the military during WWII. We all volunteered. One of us did not come back. The three older boys were in the Army Air Corps, one younger brother was in the Army, and I served as the only sailor in the family with the unheralded amphibious forces that island-hopped its bloody way to Japan. The environment of the world, the times, the war, and most of all the shaping of the minds of the 15 million young people in uniform is the key to understanding how it was back then. Most of us were teenagers. We couldnt legally drink or vote. We were the children of the 1930s and we carried our experiences from childhood and the Great Depression into the Great War of the 1940s.

On December 7, 1941, the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, where they destroyed a number of our capital warships and killed thousands of men. We were not at war when they attacked, and there was no advance warning. By the spring of 1942, the Japanese had conquered the Philippines, Singapore, much of Southeast Asia, Guam, Wake Island, and New Guinea. In less than four months they had effectively built a wall around the vast central and southwest Pacific ocean. They had killed, driven out, or captured Allied forces in order to do so. Imperial Japan was well positioned for further conquests. After Pearl Harbor, American isolation was no longer an option. Our choices were limited to fighting for our freedom and utterly defeating our enemies, or surrendering to them. There was no middle ground.

On the other side of the world in Europe, Nazi Germany had enslaved France, Poland, Czechoslovakia, Austria, Romania, Holland, Belgium, Norway, Finland, Greece, and Ethiopia. Most of western Russia had also fallen to invading Axis forces. England, driven off the European mainland in 1940, was locked in a death struggle to stave off a German invasion of its homeland. Would it survive long enough to turn the tide with the help of American troops and equipment? No one knew the answer to that question. The Free World had reached its nadir.

The Japanese intended to take all of Burma, India, Australia, Midway, the Aleutians, and Hawaii before forcing us to surrender to avoid an invasion of our western states. Japan and Germany were allied in their war against the Western democracies. Japan had nine million men in the military, twice as many fighting ships and aircraft carriers as we did and perhaps more importantly, a home field advantage. Our troops numbered fewer than one million at the beginning of the war. After losing most of our battleships and fighter aircraft at Pearl Harbor, the United States Navy was hard pressed to carry the war against its Pacific enemy.

We had to do the impossible, and do it immediately: carry the war into Japanese waters while assisting England in defeating Germany thousands of miles away. The specter of a two-front war was a daunting one, but the alternative was unthinkable. In order to stop Japan, we had to move our troops and equipment 6,000 miles across the ocean in ships we didnt have to fight an enemy already firmly entrenched on scores of islands with air fields, supported by a powerful navy several times the size of our own battered fleet.

And we did it.

D-Days In The Pacific is the story of how we achieved this remarkable feat, as told through the eyes of a teenager in command of his own boat.

Acknowledgements

For D-Days in the Pacific, the list of contributors is long because it spans a half-century of my life. It begins in the first third of the last century with family, followed by my friends, my shipmates, and business associates. Many do not realize the contribution they supplied. The greatest help came from those who were honestly critical of my effort, but gave me encouragement along the way. My greatest fear is that I overlooked someone. If I did, and you dont find your name here, please know I appreciate your efforts.

First, I want to extend thanks to David Farnsworth of Casemate Publishing for taking a chance on an unheralded author because the humane nature of this book and its illustrations tell a story that needed to be told.