FOREWORD

T o be openly proper and conventional yet also openly daring is a way of being that was seldom available to women in the past. Some who did pull off this trick without being either aristocratic or rich were Americans on the frontier. Hannah Breece was one of these women.

To her great-nephews and great-nieces, of whom I was one, she had the glamour of a storybook heroine. She camped out with Indians! She held a hundred wild dogs at bay by herself and escaped them! She traveled in a kayak wearing bear intestines! A bear almost ate her right from her bed, and this time the dogs saved her!

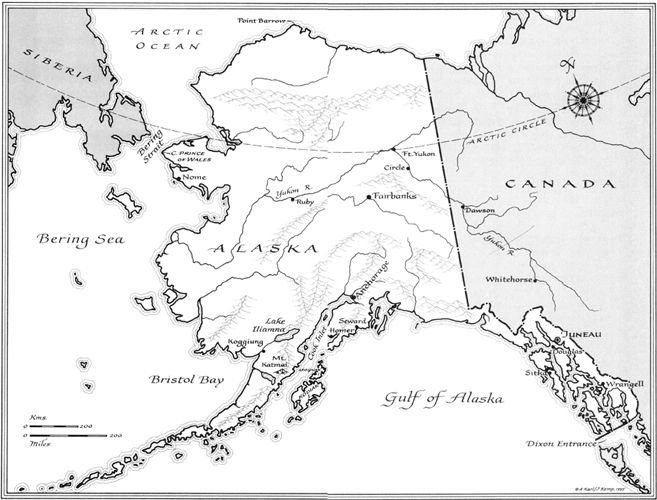

Hannah Breece was no rash or spry young thing in a band of spry young things when she experienced exotic perils. She was a middle-aged woman essentially on her own. Her job was serious and responsible: teaching Aleute, Kenais, Athabaskans, Eskimos and people of mixed native and European blood in Alaska from 1904 to 1918. She was forty-five years old when she went to Alaska and fifty-nine when she completed her assignments there, a fact to remember when we observe her, in her memoir of those years, scaling cliffs, falling through ice or outracing a forest fire. That was part of the daring. She did those things encumbered by long and voluminous skirts and petticoats. That was part of the propriety.

While her memoir is not a diary, it is diary-like in its mingling of domestic matters, work, public events and chance encounters. At the time of which she writes, all Alaska had fewer than 65,000 persons, and for some of those years closer to 55,000, both native and white, but that small population assayed high in outre or otherwise extraordinary characters who come matter-of-factly into her story: gold prospectors and fur traders; tribal chiefs and wise men; ladies in black silk and dressy hats meandering among the stumps and briars of primitive Seward; bounders who took off in boats after fathering children; Russian Orthodox priests; tellers of strange tales.

The self-portrait that emerges from her memoir jibes exactly with my memory of her when she was elderly. In personality and character she much resembled the fictional Jessica Fletcher portrayed by Angela Lansbury in the television series Murder, She Wrote. That is, she was forthright and spontaneous but with wondrous funds of self-control; she did not shrink from making judgments but was so intuitively sympathetic in most instances that her judgments could be taken in good part. She was inexhaustibly interested in the ordinaryor better yet, extraordinaryminutiae of daily life. While she was not one who used charm in a conscious way to get what she wantedshe was anything but manipulative people liked being around her, in part because of her resourcefulness and dependability and in part because she was good, lively company. She even looked somewhat like Angela Lansbury with her soft, rounded cheeks, regular features and intelligent, engaged eyes. However she was not elegant, although she could have been had she so chosen.

Some of her stories have resonances for us she could not have imagined. The story of Gregory echoes against Lenin's tomb with its lines of visitors gazing at a preserved corpse. The tribulations of the Russian bishop, who was too liberal, and Miss Vonderfour, who fell out of favor with the Czarina, merge into those of other dissidents under other regimes. Now and again she relates bits of short stories for which only the reader can try to supply missing parts. How in the world did penniless Mrs. Miller get from Wales to the Klondike, and whatever possessed her to acquire that awful husband? Hannah is not telling, either because she did not know or, more likely, because the facts would have reflected badly on Mrs. Miller. What is one to make of the deplorable Reindeer Man? What I made of him was an uprooted fellow, not too bright, who dreamed of a coquettish woman at his beck and call and conned distant bureaucracies into collaborating with his fantasy. Imagine his horror when solid, middle-aged Miss Breece materialized in the wilderness and (I am looking at this through his eyes) brazenly commandeered all the men in sight to do her bidding.

In some waysthis was part of the propriety againshe was formal, hewing to the etiquette of her time. For example, she did not address even old and good friends by their first names, nor did they address her as Hannah. She was Miss Breece. Her Alaskan pupils and their parents and fellow villagers addressed her as Teacher, much as we would say Professor or Doctor. Her letters found in government archives are often in pencil on lined schoolchildren's notebook paper, but even so not informal; they begin, Sir: I have the honor to address you and those she received start with Madam:

But in other ways she was radicalthis was part of the daring. She was inventive with teaching methods and projects. She had to be; often enough, at the time pupils entered school, she and they had no language in common. Sometimes her pupils' opportunities for schooling were so short that at the same time she was teaching them, she was devising ways for them to continue by teaching each other. We catch her, in 1911, pre-inventing on a small scale a 1930s New Dealtype work-relief program when she had to contend, on her own responsibility, with how to dispense famine relief without doing the recipients harm.

Her memoir shows her as always consistent in some of her enthusiasms: championship of women and pride in women's accomplishments; the desirability of good, homemade bread; appreciation of the natural environment and concern for its preservation; scorn for superstition. She herself was devoutly religious and respected others' piety. But she drew a fine and severe line between what she deemed religious beliefs and what she deemed superstition, and this did not necessarily accord with other folks' fine lines between the two.

Although she worked closely with missionaries in several assignments and civic efforts, her attitudes were in some respects subtly different from missionaries' preoccupations. For instance, she enjoyed and appreciated love of finery, whether it was manifested in ancient costumes of feathers and fish skins, the embroidered robes of a bishop, beaded belts and moccasins, the draping of wedding veils, or her own handsome fur boots trimmed in beaver. The silk and satin party dresses that Athabaskan women made for themselves would doubtless have fallen, from a missionary viewpoint, into the category of what the Episcopal archdeacon of the Yukon called glittering trash. But to admiring Miss Breece they were evidence that the women had an excellent sense of style and were natural-born dressmakers.

In one of her causes it is fair to say she was fanatic. She was an implacable, relentless prohibitionist. She became so, she once told me, by having seen the effects of alcohol on families and communities while on earlier teaching assignments on Indian reservations in the Rocky Mountains. She pronounced alcohol the curse of the north and at one point in her memoir we see her, like a Carry Nation, personally dumping a barrel of home brew down a riverbank.