Yu Hua - China in Ten Words

Here you can read online Yu Hua - China in Ten Words full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2011, publisher: Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, genre: Non-fiction. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:China in Ten Words

- Author:

- Publisher:Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group

- Genre:

- Year:2011

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

China in Ten Words: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "China in Ten Words" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

China in Ten Words — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "China in Ten Words" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Also by Yu Hua

Brothers Cries in the Drizzle Chronicle of a Blood Merchant To Live The Past and the Punishments

Translation copyright 2011 by Yu Hua

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Pantheon Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. This work, originally written in Chinese, was first published in France as La Chine en Dix Mots by Actes Sud, Arles, France, in 2010. French translation copyright 2010 by Actes Sud. A Chinese edition of this work was published in Taiwan as Shige cihui li de Zhongguo by Rye Field Publications, Taipei. Copyright 2011 by Yu Hua.

Pantheon Books and colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

A portion of this work was originally published in different form in

The New York Times .

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Yu, Hua, [date]

[Shige cihui zhong de zhongguo. English]

China in ten words / Yu Hua; translated from the Chinese by Allan H. Barr.

p. cm.

eISBN: 978-0-307-90693-9

I. Barr, Allan Hepburn. II. Title.

PL 2928.h78s5513 2011 985.185207dc22 2011010320

www.pantheonbooks.com

Jacket design by Peter Mendelsund, Brian Barth, and Linda Huang

v3.1

contents

introduction

I n 1978 I got my first jobas a small-town dentist in south China. This mostly involved pulling teeth, but as the youngest staff member I was given another task as well. Every summer, with a straw hat on my head and a medical case on my back, I would shuttle back and forth between the towns factories and kindergartens, administering vaccinations to workers and children.

China during the Mao era was a poor country, but it had a strong public health network that provided free immunizations to its citizens. That was where I came in. In those days there were no disposable needles and syringes; we had to reuse ours again and again. Sterilization too was primitive: The needles and syringes would be washed, wrapped separately in gauze, and placed in aluminum lunch boxes laid in a large wok on top of a briquette stove. Water was added to the wok, and the needles and syringes were then steamed for two hours, as you would steam buns.

On my first day of giving injections I went to a factory. The workers rolled up their sleeves and waited in line, baring their arms to me one after anotherand offering up a tiny piece of red flesh, too. Because the needles had been used multiple times, almost every one of them had a barbed tip. You could stick a needle into someones arm easily enough, but when you extracted it, you would pull out a tiny piece of flesh along with it. For the workers the pain was bearable, although they would grit their teeth or perhaps let out a groan or two. I paid them no mind, for the workers had had to put up with barbed needles year after year and should be used to it by now, I thought. But the next day, when I went to a kindergarten to give shots to children from the ages of three through six, it was a different story. Every last one of them burst out weeping and wailing. Because their skin was so tender, the needles would snag bigger shreds of flesh than they had from the workers, and the childrens wounds bled more profusely. I still remember how the children were all sobbing uncontrollably; the ones who had yet to be inoculated were crying even louder than those who had already had their shots. The pain that the children saw others suffering, it seemed to me, affected them even more intensely than the pain they themselves experienced, because it made their fear all the more acute.

This scene left me shocked and shaken. When I got back to the hospital, I did not clean the instruments right away. Instead, I got hold of a grindstone and ground all the needles until they were completely straight and the points were sharp. But these old needles were so prone to metal fatigue that after two or three more uses they would acquire barbs again, so grinding the needles became a regular part of my routine, and the more I sharpened, the shorter they got. That summer it was always dark by the time I left the hospital, with fingers blistered by my labors at the grindstone.

Later, whenever I recalled this episode, I was guilt-stricken that Id had to see the childrens reaction to realize how much the factory workers must have suffered. If, before I had given shots to others, I had pricked my own arm with a barbed needle and pulled out a blood-stained shred of my own flesh, then I would have known how painful it was long before I heard the childrens wails.

This remorse left a profound mark, and it has stayed with me through all my years as an author. It is when the suffering of others becomes part of my own experience that I truly know what it is to live and what it is to write. Nothing in the world, perhaps, is so likely to forge a connection between people as pain, because the connection that comes from that source comes from deep in the heart. So when in this book I write of Chinas pain, I am registering my pain too, because Chinas pain is mine.

T he arrow hits the target, leaving the string, Dante wrote, and by inverting cause and effect he impresses on us how quickly an action can happen. In Chinas breathtaking changes during the past thirty years we likewise find a pattern of development where the relationship between cause and effect is turned on its head. Practically every day we find ourselves surrounded by consequences, but seldom do we trace these outcomes back to their roots. The result is that conflicts and problemswhich have sprouted everywhere like weeds during these past decadesare concealed amid the complacency generated by our rapid economic advances. My task here is to reverse normal procedure: to start from the effects that seem so glorious and search for their causes, whatever discomfort that may entail.

We survive in adversity and perish in ease and comfort. Such were the words of the Confucian philosopher Mencius, citing six worthies in antiquity who suffered untold hardship before achieving greatness. Man is bound to make mistakes, he believed, and it is in the unceasing correction of his errors that human progress lies. Viewed in this light, he suggested, adversity has a way of enhancing our endurance, while ease and comfort tend to hasten our demisewhether as individuals or as a nation. When I write in these pages of personal pain and of Chinas pain, it is with that same conviction that we survive in adversity. So in this quest to follow things back to their source, we cannot help but stumble upon one misfortune after another.

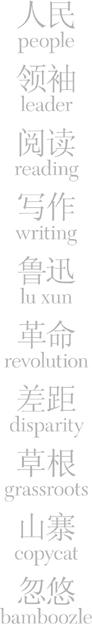

If I were to try to attend to each and every aspect of modern China, there would be no end to this endeavor, and the book would go on longer than The Thousand and One Nights . So I limit myself to just ten words. But this tiny lexicon gives me ten pairs of eyes with which to scan the contemporary Chinese scene from different vantage points.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «China in Ten Words»

Look at similar books to China in Ten Words. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book China in Ten Words and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.