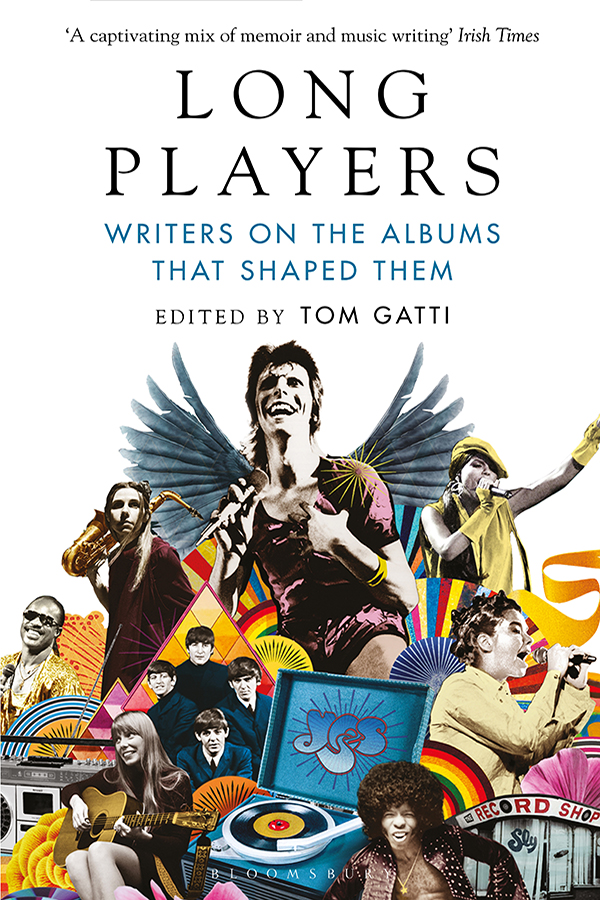

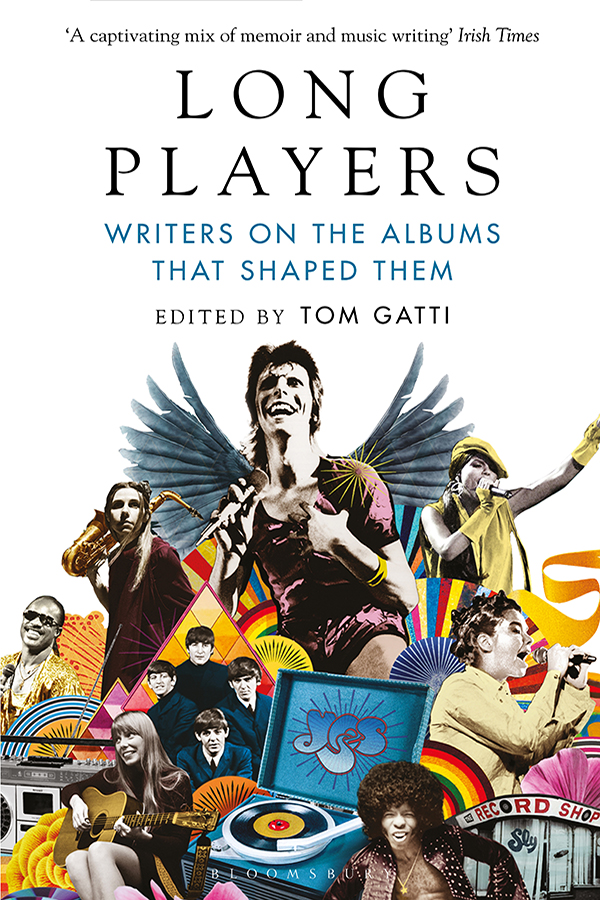

TOM GATTI works at the New Statesman, where Long Players began life as a feature. He joined the magazine in 2013 as culture editor; before that he was Saturday Review editor at The Times, where he also wrote book reviews, features and interviews. From 1995 to the present, he has listened to Radioheads The Bends more times than is strictly necessary.

BLOOMSBURY PUBLISHING

Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

50 Bedford Square, London, WC1B 3DP, UK

29 Earlsfort Terrace, Dublin 2, Ireland

BLOOMSBURY, BLOOMSBURY PUBLISHING and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

First published in Great Britain 2021

This edition published 2022

Introduction copyright Tom Gatti, 2021

Individual chapters copyright the Contributors, 2021

(further details can be found on pp. )

Tom Gatti and the Contributors have asserted their right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as Author of this work

For legal purposes the constitute an extension of this copyright page

Quotation from A Natural Disaster by Anathema reproduced with permission. Lyrics written by D. Cavanagh, published by Concord Music.

Quotation from Roundabout by Yes used by permission of Hal Leonard Europe Limited. Words & Music by Steve Howe & Jon Anderson, Copyright 1980 Universal Music Publishing Limited. All Rights Reserved. International Copyright Secured.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers

Bloomsbury Publishing Plc does not have any control over, or responsibility for, any third-party websites referred to or in this book. All internet addresses given in this book were correct at the time of going to press. The author and publisher regret any inconvenience caused if addresses have changed or sites have ceased to exist, but can accept no responsibility for any such changes

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: HB: 978-1-5266-2578-6; PB: 978-1-5266-2576-2; EBOOK: 978-1-5266-2577-9; EPDF: 978-1-5266-4459-6

To find out more about our authors and books visit www.bloomsbury.com and sign up for our newsletters

Contents

When I discovered the album, it was a form already past its prime. Michael Jacksons Thriller was released in November 1982, a few months after my first birthday. By the end of 1983, it had sold 22 million copies worldwide. Until then, no album by a solo artist had sold more than 12 million. Issued at the end of the vinyl era, it was the last album to truly conquer the world.

Not that I knew any of that when, aged seven, I pulled the record from the shelf and lay on my stomach on the carpet of our suburban sitting room. The poise of the 24-year-old Jackson, reclining in his white suit with its faintly otherworldly glow, was impressive enough. But flipping open the gatefold revealed a tiger cub on Jacksons knee a delightful surprise, and considering that my favourite piece of vinyl up to this point had been the soundtrack of The Jungle Book , subconsciously reassuring. Pulling out the inner sleeve, I was met with a dense grid of lyrics. As the hyperactive drum track and propulsive bass of Wanna Be Startin Somethin kicked in, I read along, appreciative of Jacksons habit of thorough and accurate transcription (every yeah, yeah is present and correct), perplexed by the language (who is a vegetable and why?) and intrigued by the weird line drawings. (One depicted Michael and another chap Paul McCartney, I later discovered each wearing matching tank tops and pulling the arm of an Olive Oyl-like figure, as if about to tear her in two; the other showed Michael and his paramour on a sofa, encircled by a pair of werewolf arms extending from the television screen.)

I didnt know that this was an album but it seemed to me an object full of rich meanings, a text to be deciphered, and a sound-world in which to lose myself. A year or so and many listens later, I went to a disco at my primary school and brought Thriller to lend to the DJ (misunderstanding the process, or simply not having much faith in his record collection). He humoured me, obligingly giving Billie Jean a spin and when he returned the album, he generously slipped something in the sleeve: his own 7-inch of Smooth Criminal. On the reverse of the sleeve was an inset image of Michael in a black leather jacket adorned with buckles and zips, and the fateful words: Also available: Michael Jacksons LP Bad . The golden age of the LP might have been over, but for me it had just begun.

*

The gramophone record, made of heavy, brittle shellac and spinning at 78 revolutions per minute (rpm), dominated recorded music for fifty years. Emile Berliner, a German who had emigrated to the US just before the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War,

Through the thirties and forties, the holy grail for the record companies was a format with extended listening time: a long player. A 33 rpm vinyl disc was produced as early as 1932, but it took another sixteen years for the materials to be perfected and, crucially, a length

It would be two decades before a new generation of musicians figured out how to turn this format, designed to carry The Mikado and South Pacific , into a modern work of art a marvel for the baby boomer generation. Initially, albums were synonymous with grown-up music: classical and jazz for the musos; soundtracks and comedy recordings for those in search of light entertainment. The rise of rock and roll in the fifties and beat music in the early sixties was driven by singles, disseminated through the radio and jukeboxes and bought with pocket money or Saturday-job cash on 45 rpm 7-inch records. Albums were a by-product, a commercial afterthought stuffed with filler and sold only to fans who were sufficiently devoted or wealthy: Phil Spector, the producer most responsible for shaping the sound of the early sixties, memorably described LPs as two hits and ten pieces of junk.

But by 1965, this had begun to change. In that year the Beatles released their sixth album, Rubber Soul a mature, experimental and ambitious record, containing no cover versions and very little filler (unfortunately Ringos country number What Goes On prevents it being certified padding-free). The bands American record label Capitol did not release any singles in advance, giving the album the air of an unusually coherent artistic work. Listeners agreed. John Cale and Lou Reed were galvanised by Rubber Soul in their newly christened group the Velvet Underground; Pet Sounds .

Considering Spectors views on the album form, its ironic that Wilsons LP, released in May 1966, was partly an attempt to sustain his version of Spectors Wall of Sound approach over a whole record. It wasnt really a song concept album, or lyrically a concept album, Wilson later said; it was really a production concept album. The result was Sgt. Peppers Lonely Hearts Club Band .

If Pet Sounds and rocks first double albums Bob Dylans Blonde on Blonde and Freak Out! by the Mothers It was twenty years ago today, McCartney told us, that Sgt. Pepper taught the band to play; it had also been twenty years since the long player was born. The technology developed to contain a Beethoven symphony had spawned an entirely new form.

In 1969, just two years after Sgt. Pepper s release, albums outsold singles for the first time in Britain. The tables had turned: the 7-inch discs that had powered pop musics rise were now seen as commercial and disposable. As Bob Stanley points out in Yeah Yeah Yeah: The Story of Modern Pop ,The following year, album releases included Carole Kings Tapestry , Marvin Gayes Whats Going On and Joni Mitchells Blue .

Next page