Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC 29403

www.historypress.net

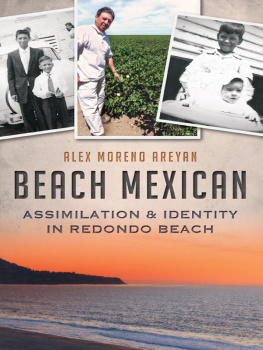

Copyright 2013 by Alex Moreno Areyan

All rights reserved

First published 2013

e-book edition 2013

Manufactured in the United States

ISBN 978.1.61423.984.0

Library of Congress CIP data applied for.

print edition ISBN 978.1.60949.661.6

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

This book is dedicated to my wife, Linda, and my children, Damian, Analisa and Ryan, for insisting I write it; all my family memberspast, present and future; and James Michael Areyan. James, I hope this book will help you understand your roots.

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

My love and gratitude to my beautiful, generous wife, Linda, for her countless hours of moral and editorial support. Her meticulous editing of multiple drafts honed my ideas and played a crucial role in completing this book. Not every writer has the privilege of having an in-house editor. She continues being mi rayo de luz (the sunshine of my life).

I am indebted to Carmen Contreras Hernandez, who has allowed me to use her term Beach Mexican for the title of this book. I am also grateful that she shared with me her encyclopedic knowledge of the Mexican American history of Redondo Beach and Hermosa Beach.

A very special thank-you to Dr. Francisco Jimenez at Santa Clara University, who provided me with my original inspiration for this book after I read his two moving books: The Circuit: Stories from the Life of a Migrant Child and Breaking Through.

My heartfelt thanks to my editor, Jerry Roberts, whom I have come to admire and trust for his unfailingly wise and incisive editorial judgment. He has been a calm reservoir of support during every step of this book. Even the title of Beach Mexican did not deter him from supporting my story.

Another person who stood by me and offered support in my moments of anxiety is my good friend columnist Don Lechman. Don made me believe in myself and this project, and he continues to support my efforts to be a writer.

An affectionate thank-you to our friends and traveling companions Bob and Maria Boiles and Steve and Joyce Lepore for their good-natured ribbing and support. Bob is still waiting for me to write a book about old white guys in Aerospace.

This book would not have been possible without the help, generosity and support of the following friends and family: Cindy Aragon; Herminda Banda; Porfiria Banda; Joe Chavez; Robert Flores; Virginia Banda Flores; Alex Flores; Nieves and Calistro Gonzalez; Margie Hart; Pat Havens and Carolyn Valdez Phillips of the Strathearn Museum in Simi Valley, California; Scott Irving Harrison; Sydne Yanko Jongbloed; Albert Juarez; Peter Serrato; Ronnie Serrato; Tere Serrato; Norm and Sally Marshall; Linda Fincham Waite; and Tom Volpi.

I received support and assistance from so many people that it is impossible to mention everyone by name. To those who I may have overlookedI apologize and assure you that any oversight is unintentional.

INTRODUCTION

My cultural assimilation experience in the South Bay was shaped by what I believe was a number of distinctive factors. Growing up in the 1950s, the Mexican American population of Redondo Beach, California, never exceeded 5 percent of the citys approximate population of forty-five thousand, with the citys core being Anglo-American. Within the section of the city known as North Redondo, the number of Mexican American families was relatively small when compared to the nearby communities of Wilmington and San Pedro, which had much larger Mexican American barrios or neighborhoods. This meant that assimilation of the Mexican American community into the majority Anglo culture was somewhat different. For example, North Redondos Mexican American section was composed of about sixty families, surrounded by the larger, dominant Anglo community and culture. Because of our smaller numbers, and despite the fact that we had been raised in our parents Mexican or Mexican American cultures, we had to assimilate into the Anglo culture quickly in order to fit in. To do this, it became important to rapidly adapt and incorporate the English language and culture into the Spanish language and culture in our formative years and into adulthood.

The dominant Anglo culture created informal yet strong peer and social pressure to conform to the dominant culture. Because the Mexican American neighborhood in North Redondo was much smaller than other places such as East Los Angeles, the assimilation experience was different. My old neighborhood did not have many of the cultural identifiers of a typical barrioschools with large Mexican American enrollments, ethnic community halls, clubs or small neighborhood stores with Spanish signage and advertisingthat strengthen ethnic ties and identity but sometimes slow assimilation. What North Redondo had was something of an ethnic scattering of Mexican American residents. What the neighborhood did have, in many cases, were bilingual parents who, despite knowing two languages, tended to have their children grow up speaking English as their first language. Many children had a working understanding of Spanish but never learned to speak more than a few Spanish words themselves. Some parents would tell their grown children that their insistence on having them speak English exclusively was a way to protect them from the discrimination they had experienced while speaking Spanish at school in their youth. Regrettably, this encouraged an environment wherein only when absolutely necessary would children acknowledge their Mexican heritage. Indeed, they would sometimes claim to be descendants of more culturally acceptable groups such as European Spanish, Spanish/French or other combinations.

In my case, because I am the son of a Mexican immigrant who spoke no English and a first-generation Mexican American mother, I was predisposed to inherit my fathers language, values, customs and traditions. For the first five years of my life, I thought and lived in a Spanish-speaking, Mexican American world. It was not until I entered elementary school that the gradual and sometimes awkward process of my assimilation into the dominant American culture began. Prior to elementary school, I needed English only to communicate my needs to the Good Humor ice cream and the Helms Bakery truck drivers who trolled through the old neighborhood.

Originally, the concept of this book centered on describing my early childhood social assimilation experiences up to my high school years. However, in an effort to show that assimilation continues into higher education, I have included a chapter covering this period.

This book chronicles what it was like for a Mexican American male growing up in an area known by local residents as the South Bayan area generally perceived as middle class and, in some cases, financially affluent. There are exceptions to this perception, however, as will be explained in this book. My assimilation experiences include a distressing eight-year period during elementary school and high school in which I joined my family journeying as migrant workers across the great central valley of California and later in the San Fernando Valley.

Next page