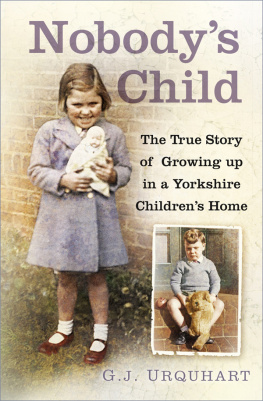

The terrifying story of life in a children's home, and a little girl's struggle to survive

This eBook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author's and publisher's rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

Sue Martin has asserted her right to be identified as the author of this Work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

This electronic book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher's prior consent in any form other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser

The Random House Group Limited Reg. No. 954009

Addresses for companies within the Random House Group can be found at www.randomhouse.co.uk

To buy books by your favourite authors and register for offers visit www.rbooks.co.uk

Preface

I wish to make it absolutely clear to readers that this is a story of what I suffered in what was then called 'Dr Barnardo's Homes' from 1944-1957. The perpetrators of the horrors I write about must be long dead and, with them, the sort of behaviour I experienced. That said, even though there were appalling Homes, there were also wonderful places run by caring, lovely people, dedicated to the welfare of the children in their charge. It was my misfortune to spend most of my time in the former and all too little time in the latter; just long enough to discover the positive experience that I was to miss out on.

Barnardo's, as it is now called, closed the last of its Homes over twenty years ago. I am glad to say that Barnardo's is, today, a very different organisation from the one I experienced all that time ago.

Prologue

My very first memory is of me, a tiny girl, standing between the knees of a man. He was wearing thick dark trousers, which felt rough against my skin; so it wasn't an entirely comfortable place to be, but I do remember feeling blissfully safe and secure. We were in a kitchen; there was a black range, a door so laden with coats on hooks that they seemed to defy gravity, and in front of me was a window. In the middle of the room a woman worked at a table; my fascination centred on the drawer she occasionally opened. The open and shut movement changed the underside of the table completely, showing bits not previously visible.

Throughout a frequently sad childhood, I comforted myself with this treasured picture, yet for years I reflected on the reality of the scene. Was I really standing by my dad before he died? Was the woman my mother, who abandoned five of us to our fate in care so shamelessly soon after the early death of our father? Was it an enduring memory of a warm, happy family life or the dream of an imaginative little girl who wished so much that it was real? Placed in Dr Barnardo's Homes at two and a half years old, without even the comfort of a doll or teddy bear at bedtime, this picture had been mine to hold on to.

When I left the Homes in 1957, fourteen years later, I described this memory to my maternal grandmother; I even drew a sketch for her. She said that it was indeed my father. In her estimation, I must have been between 18 months and two years old, and everything I told her about this scene was exactly right. The range was lit only during the winter months; by the following summer my dad had died and we left that house. However sad the circumstances it was a thrill to know my memory had been a reality.

Our personality is largely formed in infancy and a little beyond, by the extremes we see and hear; the gloriously happy and the heartbreakingly sad. We remain unaffected by the mundane and the mediocre the everyday experiences. War-torn countries and disaster areas produce traumatised children because of these extremes; horrific events mean they cannot properly develop or control their emotions. With insufficient kindness to create a balance, these children struggle and flounder, their personal horrors lasting a lifetime.

My time in Barnardo's was deeply traumatic, most especially in my formative years. Lesbian paedophilia is rarely discussed; however, my personal experience of shocking assaults carried out by certain of the all-female care staff, accounts for its existence. Aside from this horrific exploitation of power, too many of the staff frequently resorted to wanton bullying and gratuitous punishment in their desire for controlled discipline. Although impossible to ignore, I tried hard to develop a strong mind and body to cope with this misery. I decided when very young to make it a battle; my survival instinct took over, the staff became my enemies; I would not allow myself to be beaten down. Once they realised that I would not play by their rules, they sank to even greater depths of degradation and humiliation. Sometimes this proved to be a challenge almost beyond my own endurance; so I struggled harder and tried to remain undaunted. Determined to beat them, and, when older, driven by the utter misery of some of the other children treated similarly, I used my natural physical and mental strength to my advantage; the rest was sheer guile. Although my childhood journey was fraught with fear and pain, I faced it with fortitude and hope. That hope and the strong determination never to give in that was the success of my childhood. No Way Home is my account of that journey.

1

It has been many years since I left Dr Barnardo's Homes, but the first memories have not been dimmed. I was almost three years old and had just been placed in a cot; it must have been bedtime. Barnardo's seemed to have children leave and arrive in new Homes in the evening time. Perhaps I had travelled throughout the day and now awaited the next unknown in this completely strange environment.

My father had died at only 32 years old, of tuberculosis. This was my first night in the Homes away from my young widowed mother, and my five brothers and sisters.

Feeling tiny in this massive high-ceilinged room, I looked around. To my left was a large window; by sitting up at full stretch I could see outside. The sky was still a rich deep blue with soft fluffy clouds barely moving across my line of vision; silhouetted against this backdrop I could just see the tops of the tall trees. Turning away and feeling completely bewildered about where I was, I looked into the room; there were many more cots like mine lined up along the walls with other children lying in them.

In the far right corner were three or four women wearing identical green dresses with white aprons and caps. They were deep in conversation and did not seem to be aware of me sitting up. I stared at them hard, hoping one would look towards me, but no one did. For some reason I was too scared to call out and disturb them.