Contents

Guide

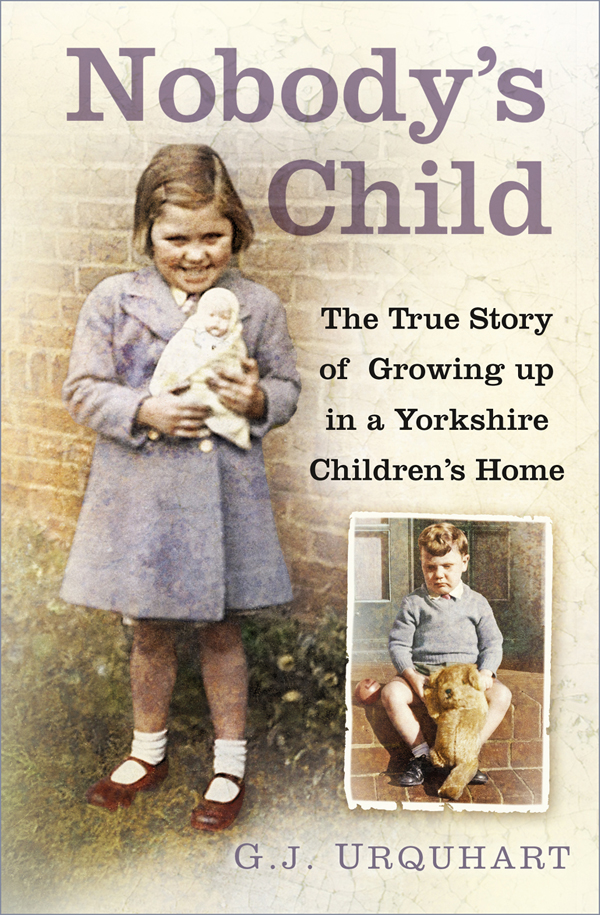

For Robert, David, Moira, Jamie, Eleanor and Ivan, with all my love.

First published 2020

The History Press

97 St Georges Place,

Cheltenham, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

G.J. Urquhart 2020

The right of G.J Urquhart to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7509 9646 4

Typesetting and origination by Typoglyphix, Burton-on-Trent

Printed and bound in Britain by TJ International Ltd.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

Prior to the Second World War, orphans and other children who were lacking parental care frequently ended up in long-term residential care provided by charities or religious organisations. In addition, children who were destitute might find themselves in the care of county and borough councils who, in 1930, had taken over the responsibilities of the former workhouse authorities, together with their stock of institutional accommodation, much of which dated from Victorian times.

In 1945, the government appointed a committee, chaired by Miss Myra Curtis, to consider how best to make provision for children who, for whatever reason, were deprived of a normal home life or parental care. The committees report recommended that for such children the best option was adoption, the next best being fostering, with institutional care the least favoured.

The reports proposals formed the basis of the 1948 Children Act, which gave local authorities the primary responsibility for providing care and supervision for any deprived child. To fulfil this broader remit, local authorities were required to appoint a Childrens Committee and Childrens Officer to put the new approach into action. However, the limited supply of suitable adoptive and foster parents meant that residential care often in rundown buildings continued to play an important role.

It was into this fledgling system that three-year-old Gloria Urquhart was thrust in February 1950 when, after the loss of her mother, she was placed in the care of Leeds City Councils childrens department. Her memoir provides a unique insiders view of this important, though rather neglected period when the modern-day care system was still finding its feet. Much more than this, though, her vivid and extraordinarily detailed memories of the people and places she encountered make compelling reading. Her life in the councils various homes veered between violent abuse and warmth and kindness, while a taste of life outside came via a weekend aunt and uncle scheme, eventually leading to a long-term foster placement.

But at the heart of Glorias chronicle is her determination to track down her birth family, especially her baby brother, Kevin a journey whose twists and turns, joys and heartbreaks, battles with officials, and the ultimate triumph of her indomitable spirit that makes this book so captivating and moving. When I first read Glorias manuscript, I found it almost unputdownable. She is a wonderful writer and her story is one that will stay with you for a long time.

Peter Higginbotham

childrenshomes.org.uk

One

IDENTITY

Your mother is dead and in a box with a lid on. You are not wanted! shouted the woman who was stripping off my clothes.

I was so scared. If my mother was in a box, would a lid be put on this thing I was standing in? Would I soon be dead?

In reality, I had just been plunged into a large, white porcelain bath of hot soapy water and my hair covered with the foulest smelling cream, which quickly took away the terrible itching that made me scratch. I had never had a bath before. Whenever washing had been considered necessary, I was bodily lifted into the sink and scrubbed with a rough facecloth lathered with yellowish soap. Standing there in my birthday suit, I could look out over greying net curtains and watch other children playing in the street.

This new experience of a bath was so frightening. Crying was rewarded with hard slaps on my bare, wet legs that hurt terribly and left large red marks. Relieved to be physically pulled out of the bath still alive, I searched for my own clothes.

They are in the dustbin! yelled the woman. More tears, more slaps. I only wanted my own clothes! But I was forced to put on the ones provided. I was given a pair of black, ugly and very heavy shoes. I could not fasten the laces and was slapped again and told, You will soon learn.

Where are my own shoes with the buttons? I can fasten them, I cried, as I tried desperately to tuck the leather laces into the shoes given to me. I stumbled down the stairs behind the awful woman.

Surely all would be well soon. After all, I had just left my father and my baby brother, Kevin in the hall downstairs. Despite the fact that Kevin had recently started to walk, he was on this occasion wrapped in a dirty shawl and firmly held in my fathers arms. The woman who opened the door to us had told me to give Kevin a big cuddle and my daddy a kiss. I loved cuddling baby Kevin and had gladly held his tiny body against mine before being hauled off to the bathroom.

Returning to the hall, I was horrified to find no one there. I screamed and screamed as I realised I was now alone. I received such a beating from the woman who had bathed me. When the beatings ceased and I stopped crying, I was told, You are not wanted. I could not understand what she was saying. Who didnt want me? The woman said, From now on you will live here with the other children.

Broken hearted, I searched the building looking for my little brother and listened for his cry. All I could hear was the sound of lots of childrens voices, who seemed to be coming from everywhere and were heading towards a room just off the hall. A very skinny girl with dark hair and broken teeth dragged me along to a huge dining room at the end of the long, musty smelling corridor. I was told to sit next to another girl, who dug me in my ribs and warned me in a brusque voice, Shut up and eat, or you will go to bed hungry.

My salty tears trickled down into the corners of my mouth, adding some flavour to the otherwise bland food, which I was now forced to consume. That night, I slept fitfully in the strange bed, surrounded by the curled-up bodies of other girls who would wake in the morning and usher me along to the row of white stone handwash basins lining the ablution room wall. I was given a toothbrush and an enamelled pint pot already bearing a sticker with my name on. At least I had my own brush!

When it came to clothing, I joined the queue at the communal clothing store cupboard. After much searching, second-hand knickers, a liberty bodice and dress were hastily handed down to me. Again, I cried as I waited for the next instruction. An older girl took hold of my hand and gently squeezed it in a reassuring manner, which gave me a little comfort. I followed her into the dining room and began to eat the breakfast I was given.