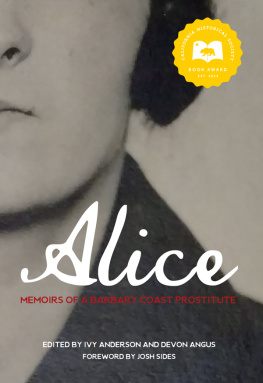

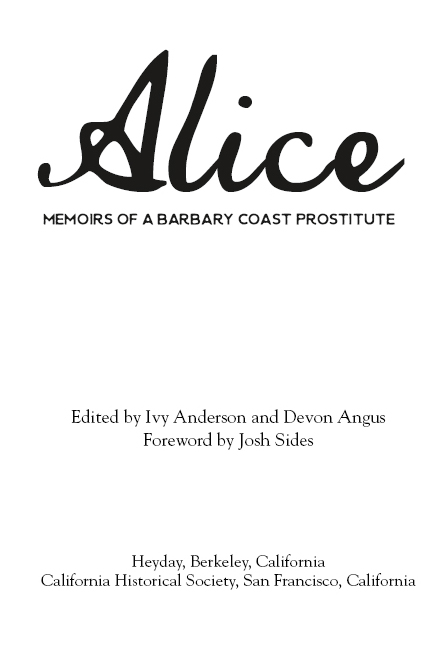

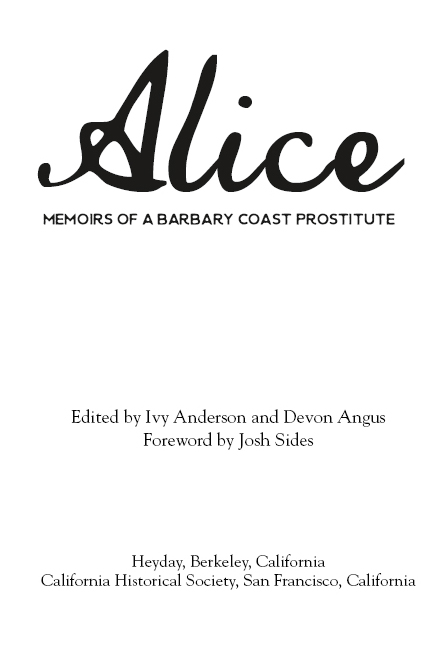

2016 by Ivy Anderson and Devon Angus

All rights reserved. No portion of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from Heyday.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Smith, Alice (Prostitute), author. | Anderson, Ivy, 1990- editor. | Angus, Devon, editor.

Title: Alice : memoirs of a Barbary Coast prostitute / edited by Ivy Anderson and Devon Angus.

Other titles: Bulletin (San Francisco, Calif. : 1895) | Voice from the underworld.

Description: Berkeley, California : Heyday ; San Francisco, California : California Historical Society, [2016] | Includes bibliographical references. | Originally published in 1913 in the San Francisco Bulletin as a serialized memoir entititled "A voice from the underworld".

Identifiers: LCCN 2016029378 (print) | LCCN 2016034563 (ebook) | ISBN 9781597143615 (pbk. : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781597143769 (e-pub) | ISBN 9781597143776 (amazon kindle)

Subjects: LCSH: Smith, Alice (Prostitute) | ProstitutesCaliforniaSan FranciscoBiography. | ProstitutesCaliforniaSan FranciscoSocial conditions20th century. | ProstitutionCaliforniaSan FranciscoHistory20th century.

Classification: LCC HQ146.S4 S65 2016 (print) | LCC HQ146.S4 (ebook) | DDC 306.74090794dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016029378

Cover photo courtesy of the San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library.

Book Design: Ashley Ingram

Printed in East Peoria, IL, by Versa Press, Inc.

Alice: Memoirs of a Barbary Coast Prostitute was published by

Heyday and the California Historical Society. Orders, inquiries, and correspondence should be addressed to:

Heyday

P.O. Box 9145, Berkeley, CA 94709

(510) 549-3564, Fax (510) 549-1889

www.heydaybooks.com

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

We dedicate this work to all of the current and former sex workers we have spoken with who have supported and shaped this project, and to the sex worker rights organizations that continue to bring their struggle to the national and international stage.

Contents

A Voice from the Underworld

Part I

Foreword

Historical scholarship takes many forms. From writing articles, monographs, and multivolume books to curating museum exhibitions and leading historical tours, the practice of revealing history is multifaceted, painstaking, and almost always illuminating. And for Ivy Anderson and Devon Angus, it is also exciting, for they found what so many historians seek in vain: a long-forgotten, almost indescribably rich primary document that has never been reprinted until nowin this case a serialized memoir of sorts titled A Voice from the Underworld. In Alice: Memoirs of a Barbary Coast Prostitute, Anderson and Angus have not only resurrected A Voice from the Underworld but also provided, in the form of an expansive introduction, a broad context for the narrative. Students and scholars of California, the Progressive era, and sexuality are in their debt.

A Voice from the Underworldoriginally published in Fremont Olders San Francisco Bulletin in 1913is a firstperson account by a prostitute named Alice Smith. That Smith was possibly not a real person but rather a composite of many working-class women and prostitutes in San Francisco at the time does nothing to diminish the power of the narrative (which was almost certainly ghostwritten by Bulletin staff). In fact, as Anderson and Angus suggest, it was the very amalgamated nature of the Alice Smith narrativewhich touches on countless aspects of the working-class experience that probably wouldnt have arisen in an account by a single individualthat encouraged so many prostitutes to respond to the narrative by writing their own letters to the Bulletin, some of which were published alongside installments of A Voice from the Underworld. According to Anderson and Angus, the Bulletin received more than four thousand letters in response to Alices story, many of which came from women, and from working-class women in particular. Above all, Alice and these women wanted to be heard.

And what they said was worth hearing. Among the details most notable to a modern reader is that both Alice and her many respondents spoke eloquently about issues that would not become popular causes until the arrival of second-wave feminism in the 1960s and the sex workers rights movement of the 1970s. Further, the interplay between the Voice narrative and the letters to the Bulletinabundantly detailed in the following pagesreveals that prostitutes were generally not the social misfits Progressive-era reformers often portrayed them to be. True, they were considered by decent society to be of compromised morality, but in turn-of-the-century San Francisco they also fulfilled a role that was more or less accepted as a necessary evil. Even then, however, it was a hard life and not one many women would choose if they could afford to do otherwise. The plight of single, working-class women of that time was essentially this: they lived in a society that simultaneously denied them livable wages for legitimate work while also circumscribing, criminalizing, and moralizing against sex work. When one goes to bed hungry many times, one prostitute wrote in to the Bulletin, the demarcation between right and wrong becomes much less in evidence and it requires some rubbing of the eyes to distinguish it at all.

Once a womans reputation was tarnished by sex work, it became nearly impossible to escape the stigma of the profession and the social alienation it engendered. Often, the only way out of this quagmire was through marriage, although more than one respondent shared the view that seeking remuneration through a loveless marriage was essentially legal prostitution. Morality, wrote fabled anarchist Emma Goldman, compels a woman to sell herself as a sex commodity for a dollar per, out of wedlock, or for fifteen dollars a week, in the sacred fold of matrimony. Alice and her respondents detailed the ways in which, for single, working-class women, prostitution was less a moral failing than it was a social inevitability.

But it was the official closure of San Franciscos vice district, the Barbary Coast, in 1917 that was the most detrimental to the well-being of the citys prostitutes. Evicting at least fourteen hundred sex workers, the closure marked the end of the sanctioned brothel (although some, like those of the legendary Sally Stanford, continued into the 1940s). A triumph for moral reformers, the end of the Barbary Coast was disastrous for sex workers because it directly endangered their safety, and sometimes their lives. Without romanticizing the brothel, Alice and her respondents generally agreed that the institution generated a sisterhood of women watching out for one anothers safety, whereas streetwalking, by contrast, offered no such safety, and more than its share of danger.

Although Alice was not particularly political, she and many of her respondents gave voice to a viciously marginalized segment of American society. In doing so they participated in something truly groundbreaking, and the fact that they did it through the Bulletin, whose readership was already at 45,000 at the turn of the century, meant they reached a large number of people from a broad cross-section of the community. Most importantly, they called on society to recognize their common humanity. Cant people understand, Alice asked, that they are all responsible for each other in lots of ways? It was the question of her time and may just be the question of ours.

Next page