Gucci. A successful dynasty as recounted by a real Gucci

by Patrizia Gucci

All photographs published in this book come from Patrizia Guccis private collection. The publisher remains available for any iconographic sources not identified.

Publishing director: Jason R. Forbus

Graphic design and layout by Sara Calmosi

ISBN 978-88-3346-907-2

Published by Ali Ribelli Edizioni, Gaeta 2021

Series Memoir

Italian edition published by Mondadori Libri S.p.a., Milano

Any reproduction of this book is strictly forbidden, even partially, with means of any kind, without the clear authorisation of the Editor.

To my family.

Foreword

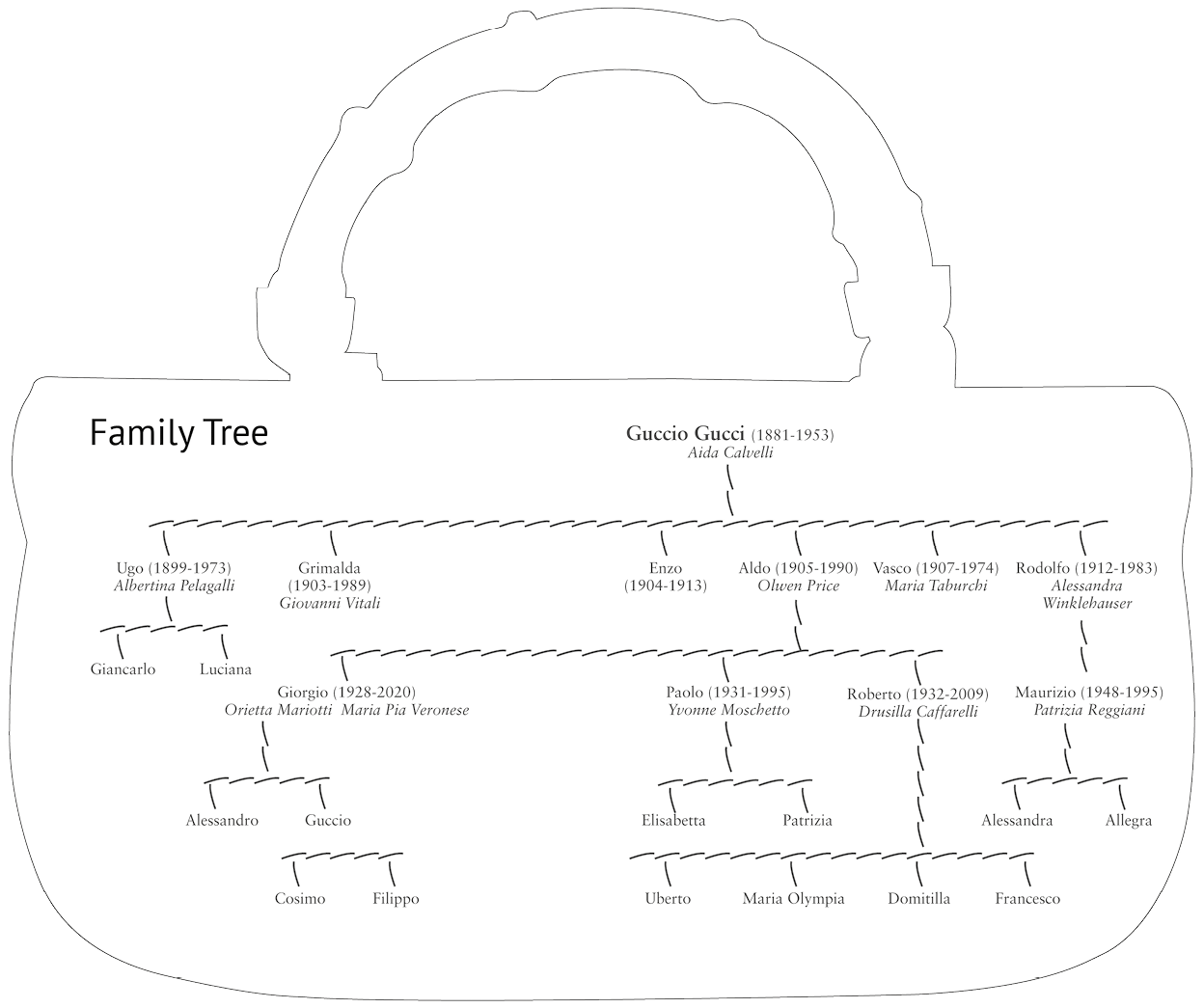

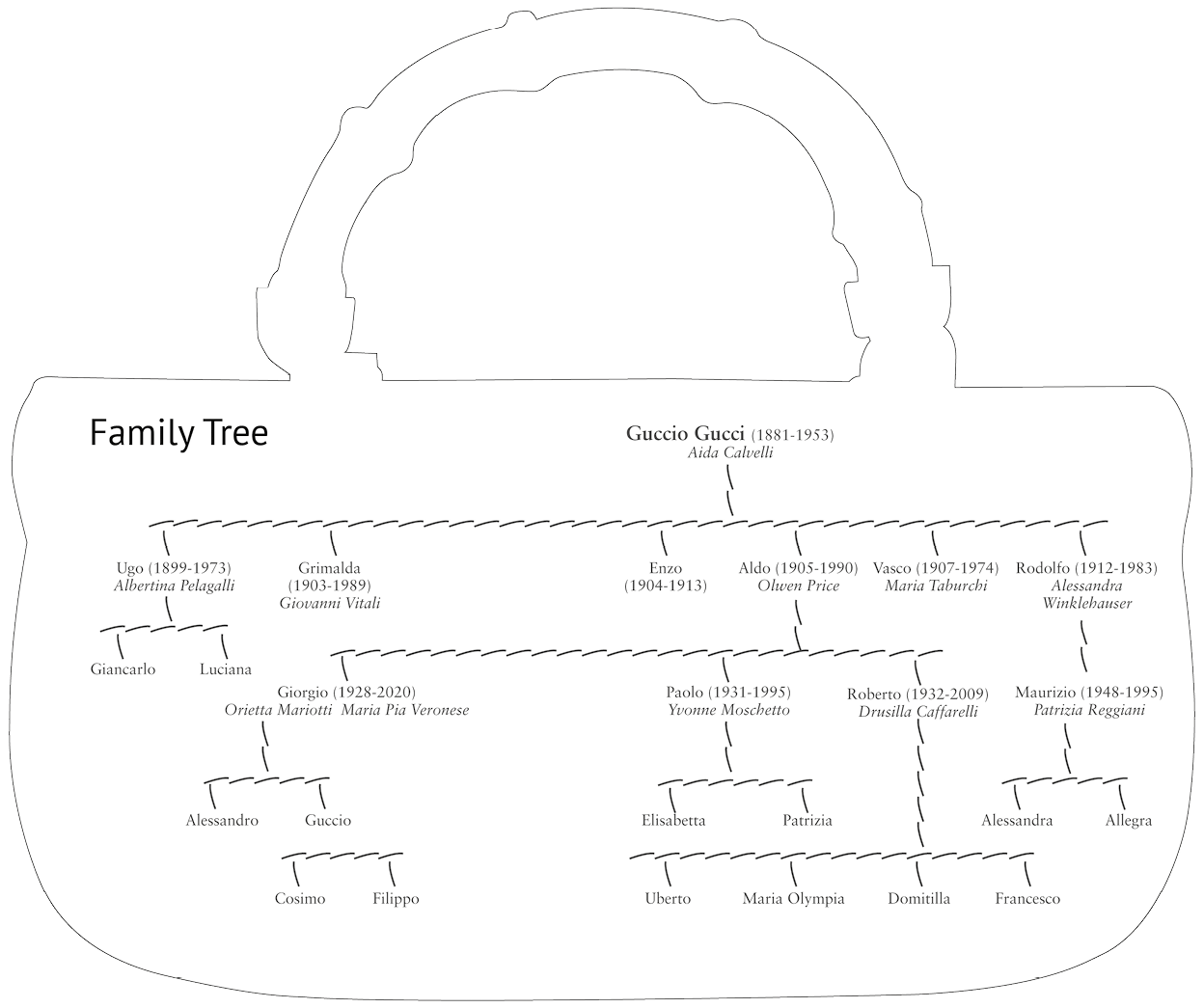

M y name is Patrizia Gucci. The company bearing my surname was created in Florence by my great grandfather, Guccio, at the beginning of 1900s when it was just a small workshop.

Today, the company is a multinational but that Gucci has nothing to do with us. The last time I entered a Gucci shop, nobody even recognised me and a wound in my heart opened once again.

This is why I want to tell my story, to bear witness to the history of my family.

But let me start first of all with another loss.

My father Paolo

T he memory of my father waving goodbye to me at London Airport is still engraved in my mind.

It was autumn 1995. After my fathers last visit to our home in Florence, I was returning after having accompanied him back to England, where he lived. I watched his hand move as if he wanted to brush away the life that was slipping away from him the life he would no longer live. For he died two weeks later.

How many times have I recalled that gesture that pains me so deeply to this day? It was the beginning and perhaps the end of a very long chain of events and inner searching, evidence of an intense relationship between a father and his daughter.

A few days earlier, my father had come to Florence from Sussex, where he was living with a new female companion. He had come to see my mother, Yvonne, just three months after his last visit. Though separated, they often met up and called each other. During the last telephone call, my mother had detected a strange tone in his voice. I, too, was shocked when I first saw him he had lost a lot of weight and was quite pale.

My mother immediately gathered a team of doctors and made appointments for tests at the hospital. That night, Paolo slept alongside her and, holding her hand, confessed that she was the only woman he had ever really loved. The diagnosis given by the doctors was alarming: Hepatitis C, last stage. The only cure was a transplant that would have to be done in England, at Kings Hospital, the best in the field. However, the danger was that he might suffer kidney failure after surgery.

My father did not appear particularly alarmed when he heard the news. He had been suffering from liver problems for some time, even though he played them down. The day before leaving for England, he left some shirts to be laundered with my mother, saying he would collect them on his next visit. He hugged me tightly, as he had never done before, and even complimented me, saying how elegant I was also something that had never happened before. It was most unusual behaviour for him.

The following day, he and I drove to the Florence airport. We were flying together to London then I would fly straight back to Italy. I helped him pack his suitcase then we tended to the waxbills, tropical red and orange birds that he was temporarily keeping in my mothers garden. My father had always had a great passion for animals and, true to his grand ways, he had just bought fifty of these passerines. He wanted to take the whole lot back with him to England but I managed to convince him to take only two, which we placed in a shoebox with holes in the lid.

Sensing he was truly unwell, I could barely hold back my tears. Yet, nothing seemed to suggest that deep inside he knew his time was drawing near. It was clear to me that he had accepted his fate. I later came to know that his doctors had given him a device that he was to have on him at all times, as it which alert him with a beep when an organ became available for a transplant. Yet, he cast the device aside, not wanting the operation out of fear that he would have to spend the rest of his life as an invalid.

Faced with losing him, I realised how much I loved him but also how much he had caused me to suffer. Although we had always had a complicated relationship, I felt I wanted to help him and ease his suffering now that we were spending our last moments together. But I didnt know how.

We left my mothers house on the hill of Poggio Imperiale, where my parents had lived together so many years and which now brought back a wave of memories.

Built in the 1960s, the house had been painstakingly designed, with large fireplaces and English-style windows looking out onto the garden. The top floor consisted of an attic and a large terrace, where my sister and I had spent much of our time so much so that it had gradually become our special realm. It had a park that had been designed by a famous Florentine landscapist, who had a knack for making the most sophisticated garden look natural. There were sycamores, Tuscan pines, red hibiscus and iris of all colours, including the very rare black variety.

Our journey to London was not easy. We needed a wheelchair to take my father up to the plane. I walked beside him carrying his grey raincoat over my left arm, holding the shoebox with the birds in my right, making sure it would not be spotted. I made light conversation with my father but kept a watchful eye on the customs officials, fearing they would notice my compromising baggage.

In those moments, I mentally pictured the entire course of our life together: the pleasant times and the disappointments, the reprimands and the praise. It hurt me deeply to see him so tired and resigned to his fate.

For many years, since the early 1980s, my father had chosen to live in his beloved England, where he devoted himself to breeding the horses he most adored Arabians. In Rusper, Sussex, he searched for and found a large estate with a manor house that he restored with style and elegance. On the property, he built a magnificent stable for his horses. Music was always played in the stable, as he was convinced that it cheered up the animals. Each horse had its own blanket with its name and Stable PG embroidered on it. The saddles too were original creations, with the dominant colours always being red and black.

Although he was now living in England, my father often came to Florence for business and also to get back in touch with his Italian side, which deep down he missed. He longed for Tuscan food and so off we would go to Trattoria Omero a must whenever he would visit. There we would gorge on typical Tuscan fare: pappardelle with hare sauce, penne strascicate or fried rabbit with courgette. It was always lovely to have lunch with him finally, he would devote some time to me. Not to mention, he had those funny Anglo-Tuscan ways that so amused me. Even his way of dressing was totally original. I remember him wearing a yellow tie with an emerald green jacket, colours only he could wear.

When he was in Italy, he felt British and speaking a mixture of English and Italian would criticise the shortcomings of Italians. Yet, when in Britain, he felt Italian and loved upsetting the phlegmatic British in his rapid-fire English and with the jaw-dropping speed at which we so recklessly drove.