Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

To Tim and Sibella, who showed me what an art world is

The three young artists hatched their plan, out of the blue, at an overpacked caf in the Left-Bank quarter of Montparnasse. In the torrid mid-July, in the too-warm wool suits of the early 1880s, they all hankered to escape the hot pavements of Paris and its rowdy Bastille Day crowds. Their ringleader, the rising star American painter John Singer Sargent, had just hit on the perfect solution. Why not catch one of Baron Rothschilds fast overnight trains to Holland, the land of Johannes Vermeer, Rembrandt van Rijn, and Frans Hals?

Twenty-seven-year-old Sargent, though lanky, dark-bearded, and rather solemna card-carrying workaholicenjoyed a good lark. At the prospect, his sedate surface broke. He flashed a little of the impudence that most people saw chiefly in his stylish, unconventional paintings.

Sargents friends well understood that his still-water mysteries ran deeper than most people knew. He was deeply passionate about painting. Though an edgily modern artist, he didnt underestimate Old Masters, as the nineteenth century understood them; he didnt consider them pass, stiff, or pedantic. Hed been infatuated, for a while now, with the splendors of Frans Hals. He adored that impudent seventeenth-century portraitist of swaggering, rich-costumed burghers, an artist no one else in Paris seemed to appreciate quite enough. And hed also made a private religion of the seventeenth-century Spanish firebrand Diego Velzquez. Past artistic revolutionaries offered Sargent intriguing keys to painterly secrets as well as a vivid and emancipatory life. He was equally inspired by the bold new Parisian portraiture of the 1880s, of which he was already, at his young age, a leading light.

His friends, drawn to his enigmatic qualitiesand yet kept at bay by themsensed that this sudden trip qualified as personally important to him. It channeled one of his sudden, heartfelt desires.

The diminutive, combustible Paul Csar Helleu especially delighted in Sargents mysteries. He was often to be found smoking a cigarette and lounging in Sargents studio. A slender, animated Breton of twenty-four, Helleu was immediately game to go.

The third conspirator, Albert de Belleroche, hung back a little more. This half-aristocratic, rather elfin Anglo-Belgian, just turning twenty, had only recently come to Paris to study art. He was just finding his feet in the painterly world. But hed gone to quite a bit of trouble to pursue Sargents friendshipwas intrigued by the older mans color-soaked canvases and surging reputation. He also appreciated Sargents habitual good humour and his willingness to undertake activities full of surprises and imprvuthe unexpectedness, now, of this spur-of-the-moment trip.

As the three friends gathered at the great glass portals of the Gare du Nord, nesting their carpetbags together, they paused beside a huge Roman arch of Lutetian limestonecalcaire grossier, the Parisians called it, coarse limestone. But this limestone, from the nearby Oise Valley, actually appeared as smooth as butter and creamy in color, facing many of the public buildings in Paris and lending that great, electric-lit, modern metropolis its luminous, subtly consistent palette of pale gray, pale gold.

Almost everything in Sargents Paris glowed with such visual style. Sargent was immersed in the latest Parisian trends, and his painter comrades were more than willing to follow where he led.

Even among friends, Sargent could be shy, formal, socially awkwardfond of sitting back and obscuring himself in the fog of his endless cigarettes. Yet his little railway junket with his artist chums revealed another Sargent. His companions sparked a species of elation, not to mention at-ease intimacy, that liberated a more spontaneous and less filtered version of the young painter. At the palatial station, on the express train, Sargent flared into enthusiasms, jokes, and confidences. He waxed joyous and daring. He called Helleu Leuleu and Belleroche Baby Milbanka reference to the surname the young painter was using at the time, as well as to his younger age. The young artists buzzed with inside jokes, shoptalk, and art-insider fandom.

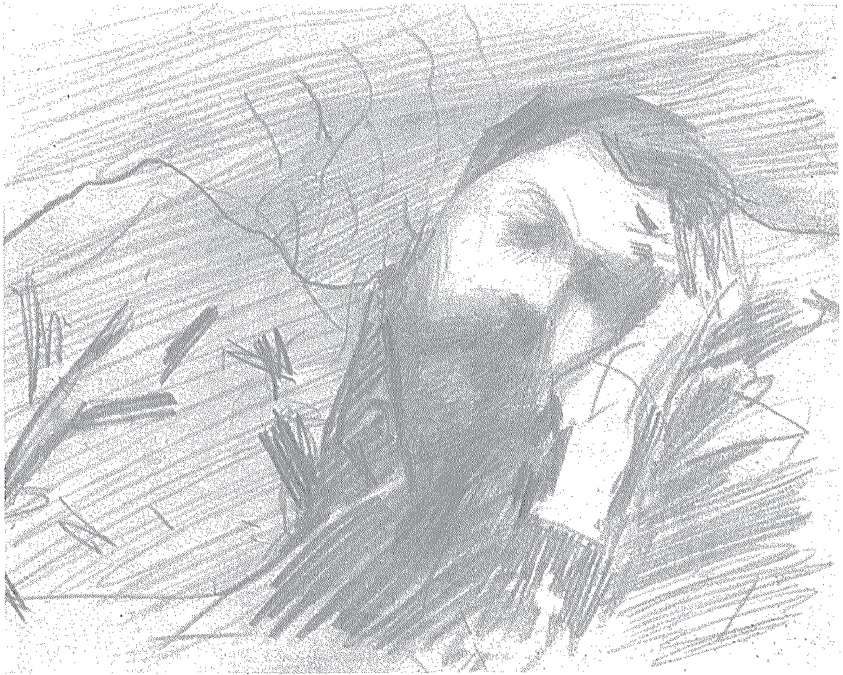

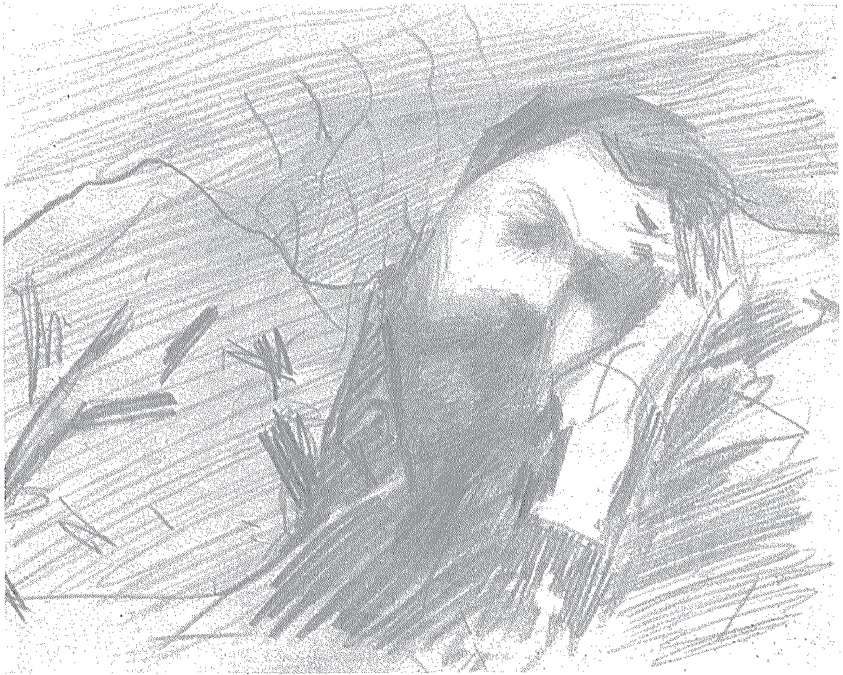

As the train rocked northward, the young men found it hard to sleep. Their overnight in the high-end sleepers called Wagon-Lits, inspired by Pullman cars in the United States, granted them all a whiff of luxury and adventureeven if their cramped, fold-down berths provided a rather coffin-like discomfort. And thats perhaps why, as the last hot light failed across the bleak and stubbly plains of northern France, Albert de Belleroche packed out a pencil and a hand-size notebook and risked a sketch of his drowsing friend.

Belleroches sketch of Sargent, 1882 or 1883

What Belleroche captured, though not obviously striking, spoke volumes. It revealed an off guard, informal Sargent with his left hand pillowed under head, his shoulder bunched up in his jacket, his fingers curled against his forehead. Whats more, though Sargents short beard and mustache remained shadowy, Belleroche rendered his face as handsome and luminous as an angels. Belleroches rather dreamy image, in fact, revealed an intimate and private vision of Sargent that Belleroche wouldnt share with others till decades later, after Sargents death. For this sketch illuminated a side of the two mens life, threaded with private meanings, that few people suspected.

Whats more, Belleroches sketch was actually just the tip of an immense iceberg. In fact, Sargents own renderings of Belleroche were ten times as plentiful. Back at his studio in the boulevard Berthier, Sargent had reeled off many sketches and half-finished canvases of his younger friend. These included moody, lyrical views in charcoal and oils, capturing the young mans delicate features and Cupids-bow lips. Such mementos littered the shelves, tables, and easels of the studio.

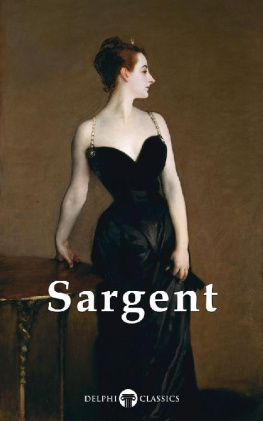

In a mania for sketching his friend, Sargent even considered producing a grand exhibition portrait, with the young man styled as a sort of Velzquez prince, draped languorously over an enormous sword. With the exception of Madame Gautreau, Belleroche later admitted, referring to Sargents infamous Madame X, I do not believe that Sargent ever had so many sittings as for this portrait. Yet Sargent would eventually abandon this princely set piece. Or rather he would alter it, rendering it smaller, more emotive, and more personal.

Sargent with Madame X in his Paris studio, c. 1884

Hed also keep his images of Belleroche quietly in the semiprivacy of his studio. He would never exhibit them in the grand, sunlit halls of the Salon.

Sargents recent and sudden celebrity had first taken wing in another limestone-faced glass greenhouse, some three miles from the Gare du Nordthe so-called Palais de lIndustrie in the Champs-lyses. That great iron-and-glass-vaulted hall, built originally for Louis Napolons 1855 Exposition Universelle, hosted the worlds most prestigious exhibition of paintings, the annual Paris Salon. Sargent had exhibited at the Salon every year since 1877. Merely to have works accepted counted as an honor. But Sargent hadnt just squeezed his canvases into the corners of this massive, world-class exhibition. Hed stolen the spotlight, the limelight, and just about all of the daylight. Hed already won two Salon medals, the maximum number allowed for an artists whole lifetime.