PREVIOUS BOOKS BY DONNA M. LUCEY

Archie and Amlie: Love and Madness in the Gilded Age

Photographing Montana 18941928:

The Life and Work of Evelyn Cameron

I Dwell in Possibility: Women Build a Nation, 16201920

National Geographic Guide to Americas Great Houses (coauthor)

Copyright 2017 by Donna M. Lucey

All rights reserved

First Edition

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.,

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact W. W. Norton Special Sales at specialsales@wwnorton.com or 800-233-4830

Book design by Ellen Cipriano Design

Production manager: Julia Druskin

Jacket design by Jennifer Carrow

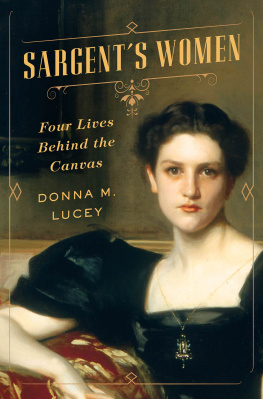

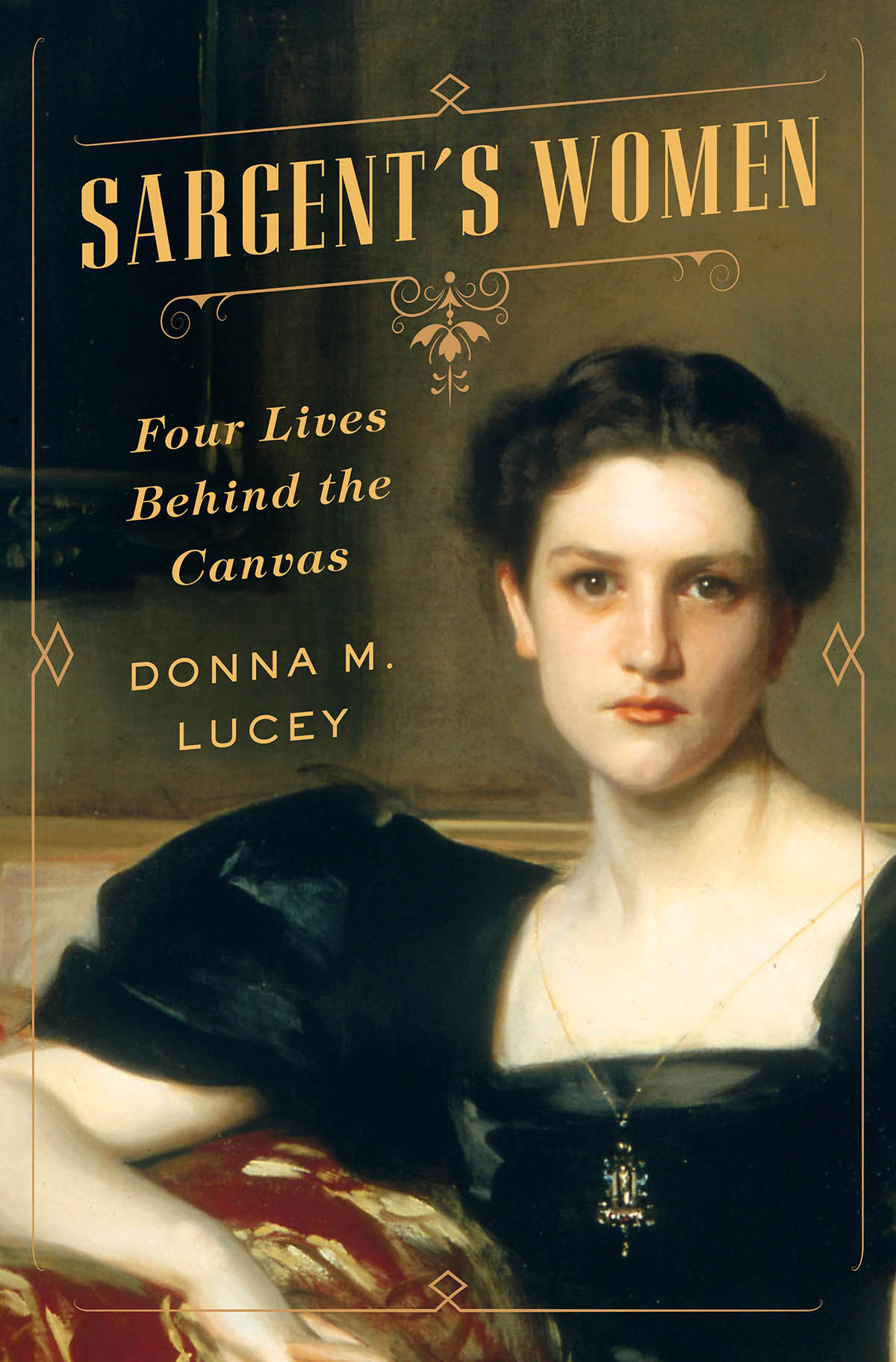

Jacket art: Elizabeth Winthrop Chanler (Mrs. John Jay Chapman) by Sargent,

John Singer (18561925), 1893. Oil on canvas, 49 38 40 12 in. Smithsonian

American Art Museum, Washington, DC / Art Resource, NY

ISBN 978-0-393-07903-6

ISBN 978-0-393-63478-5 (e-book)

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd.

15 Carlisle Street, London W1D 3BS

For Henry the Next,

with all my love

His quarry was a suitable subject, his trophy the creation of a thing of beauty.

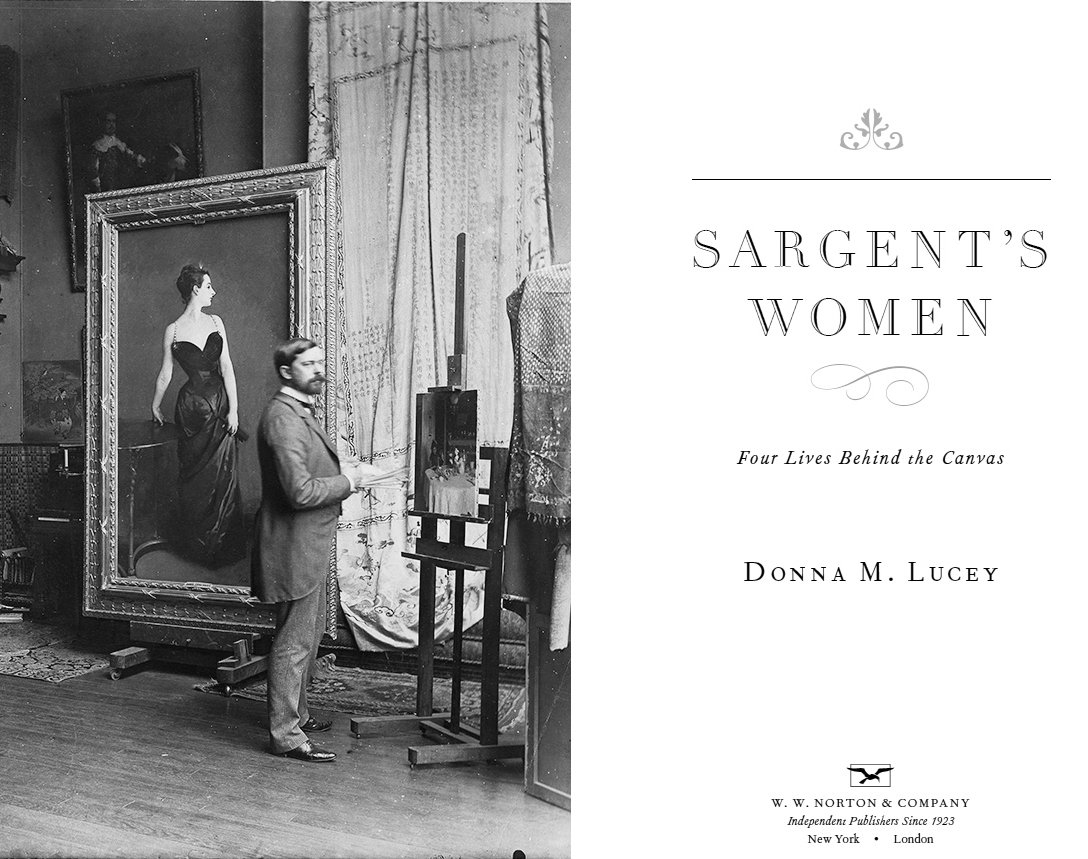

Sir Evan Charteris on his friend John Singer Sargent

CONTENTS

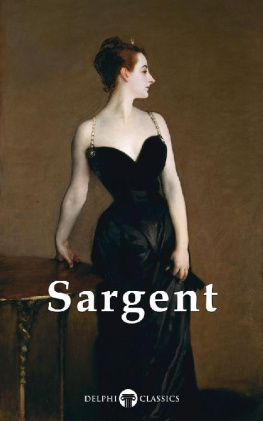

B EAUTIFUL BUT HAUNTING , these women stop you cold, make you stand and wonder: Who were these women? Something in these canvasses guides the eye to detect rustling, restless souls. Elizabeth Chanlers mournful eyes and anxious hands; Sally Fairchilds enigmatically veiled features; Belle Gardners broad shoulders and curving arms that seem to cradle something thats missing; and Elsie Palmers utter strangeness, with her blunt bangs and blank stare. You cannot help but gaze, for these canvasses contain secrets. They are images from a remote age of extraordinary, vanished splendor and they have stories to tell. At this level of art, the artifice falls away and we make a human connectiondirect, startling, unsettling. The master who created these images, John Singer Sargent, confided to an acolyte, Portrait painting, dont you know, is very close quartersa dangerous thing.

The late nineteenth century was the best and worst of timestimes much like our own, floating on a financial boom, reveling in unprecedented excess, heading for panic. Mark Twain dubbed it, sarcastically, the Gilded Age, but in a way its greatest chronicler might have been Sargent. He defined the era in his portraits of the major players.

Massive, wall-filling works made the Sargent myththat he merely slathered on the glamour for ample fees. Indeed, he became the Tiffany of portraiture, a flatterer of Gilded Age vanities; but ever more famous and ever more a creature of the market, Sargent grew to detest portraiture. Still, he was an artist and some sitters truly engaged him. Their portraits leap from the walls, and when we learn their backstories we can see whywe dont get an art history lesson but a secret guide to their emotions. From their eyes, postures, gestures, and clothing Sargent divined their internal landscapes. He could be uncannily clairvoyant in portraits of young women.

During his lifetime Sargent created over nine hundred paintings and countless sketches. So why choose these particular four women? Their portraits captivated me with their aura of intrigue, their hints of deep layers of complexity that suggested fascinating stories behind the canvasses. All of these women inhabited the gilded world. But how did they navigate through it? What choices did they make? What storms did they endure? What passions? I tell the stories of these women in the order of agebeginning with an unformed teenager and ending with a commanding middle-aged woman who is painted again in old age. Their lives played out in different places, some of them expected: the drawing rooms in New York, Boston, London, and the behemoth cottages of Newport; some of them farther afield: a castle in the Rocky Mountains, a patrician beach on the Massachusetts coast, a haunted mansion in the Hudson Valley, a Bohemian art colony in New Hampshire, a medieval, moated manor house in the English countryside, a forbidding school on the cliffs of the Isle of Wight, an ancient hotel in the Cotswolds.

I visited all these places to see where the women lived and where Sargent worked. I clambered up the steep cliffs on the Isle of Wight in search of an old girls school and explored the islands Undercliff. I rummaged through attics. I tracked down local experts who brought me to out-of-the-way places and unlocked doors to show me treasures not open to the public. I encountered a man haunted by living in the house once owned by one of the courageous, but tragic figures explored in the book. Each story became its own rabbit hole, with unexpected twists and turns. Things got very curious indeed.

All these women left voluminous collections of paperssome in archives and libraries, others in private handswhich allow me to tell their stories from the inside out. I felt the joy of holding original letters and leather-bound journals and deciphering handwritten pages. Beautiful crisp stationery and travel journals illustrated by the diarist herself and datelined from exotic locales: the spa at Baden-Baden; the cities of Paris, London, Vienna, Moscow; tiny villages in Burma, India, and Japan; frontier outposts in the American Westits a bit like Gilded Age porn to someone like myself. Theres a tactile pleasure in opening envelopes with traces of sealing wax, and touching the engraved letterheads bearing the address of a grand hotel or a family crest from an ancestral mansion. The ink is sometimes smeared across a page; the handwriting is slanted, or florid, or, in some cases, practically unreadable. The letters and diaries kept by these particular women are an art formwritten in longhand, with literary and artistic references that make modern correspondence pale. Their letters might go on for twenty pages or more, and they would write every day. It was their means of communication, their entertainment in an era before radio, television, and the nonstop cacophony of modern life. Absorbing all of their writing was not a task for the faint of heart, as it took me nearly eight years to read all of my subjects papers and then to try and make sense of it all. Poring over someones private writings is an extremely intimate act. Page after page of personal detail and the minutiae of daily life ushered me into the core of that persons world. And yet, there was always the sense that I was gazing into an inner theater where people were constructing their own characters, pursuing their own elusiveness.

Since any given scrap of paper could prove vital, my job became that of a detective, piecing together tiny bits of information from a variety of sources, not just from letters and diaries but from memoirs, from personal photographs, and ephemera of all sorts: receipts from dressmakers, invitations to balls, menus from fancy dinners, a familys guestbook; and other, more bizarre remnants from a life: a photograph of a dead body, a vial of sand, an envelope marked my curls and inside it a huge clump of auburn hair. Everything offers evidence, clues, to each womans character. Stories emerge; love affairssome secret, some notare revealed; intrigues and jealousies play out; rigid family dynamics come into view. These women were all very richor in one case, had been richso the drama was performed on an operatic scale, abetted by large fortunes and mansions, which doubled as showplaces and as stage sets for titanic family conflicts and tragedies.

Next page