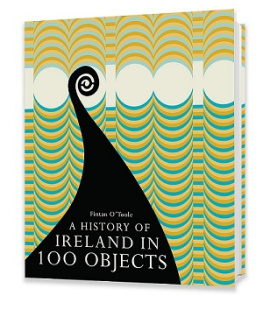

Fintan OToole - White Savage: William Johnson and the Invention of America

Here you can read online Fintan OToole - White Savage: William Johnson and the Invention of America full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: New York, year: 2009, publisher: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, genre: Non-fiction / History. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:White Savage: William Johnson and the Invention of America

- Author:

- Publisher:Farrar, Straus and Giroux

- Genre:

- Year:2009

- City:New York

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

White Savage: William Johnson and the Invention of America: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "White Savage: William Johnson and the Invention of America" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

White Savage: William Johnson and the Invention of America — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "White Savage: William Johnson and the Invention of America" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

Contents

To Clare Connell, as always

This is the first of three loosely related books. Unfolding in three different centuries and telling the stories of people with no direct connection to each other, they are linked only by a set of shared concerns. Broadly speaking, those concerns are with the creation of a modern mythology. I want to explore some of the circumstances that gave rise to Americas myth of itself, and the part played by one particular culture that of Ireland in its creation.

At the start of the twenty-first century, the big issue for people around the world is the process of globalisation. In cultural terms, globalisation is really a fancy name for Americanisation. When the marketing arms of great corporations dream of a world in which the same products and the same advertisements can carry the same freight of meaning and emotion across the globe, what they imagine is a universal America. Much of the power that America enjoys is based on the hard facts of economic and military might. But much of it, too, derives from the potency of the American epic: the conquest of a New World; the triumph of civilisation over savagery; the vestigial glamour of the defeated indigenous peoples; the invention of the white race; the allure of heroic, individualist violence.

There are obvious ways to deal with the overwhelming force of these myths. One is to go with the flow, to accept that these American stories have simply replaced the older narratives that used to underlie other cultures. The other is to retreat into a defensive redoubt of atavism and nostalgia, or, in the extreme, to construct a counter-myth from the materials of an anti-modernist and anti-American backlash. Neither of these options seems to me a good one.

There is a third possibility, though: to remember that the American myth was created by people from a wide variety of other cultures. The vivid rainbow that now spans the globe is made up of colours borrowed from many different palettes. Almost every culture on earth can unweave the rainbow in its own way. The stories that formed the basis for American mythology can be retold from any number of perspectives and, in a sense, be reclaimed by many other countries. The most powerful retellings come from the points of view of Native Americans and of African Americans; but most Asian and European cultures Chinese, Japanese, Vietnamese, Korean, Indian, Jewish, Polish, Italian, Spanish, Portuguese, Scandinavian, French, Dutch, Scottish, Welsh, English, German can follow their own threads, too, and, in the process, help to unravel the myths.

I make no special claims for an Irish perspective, though it does have some advantages. The Irish involvement in the shaping of modern America goes back almost to the beginning of the story, making it possible to take a long view. And that involvement has often had to do with mediating between other cultures. The ambivalence of the Irish situation as colonised people who became colonisers, as savages who came to see themselves as civilisers, and as white people who often appeared to official Anglo-American eyes as virtual blacks, has tended to place the Irish at some interesting crossroads. Remembering how some of them behaved at these intersections may help to unravel, not just some American myths, but some Irish ones too.

History is philosophy drawn from examples.

Dionysius of Halicarnassus

One thing leads to another. Causes have their effects. But the wind blowing on one continent may ultimately be caused by a tiny shift in the air over another. The fall and rise of the wave may be influenced by the unperceived motion of a fish. Events may be connected by broken threads whose traces form strange, irrational patterns. Otherwise, the lives of an old Irishman and a young American Indian woman could not intersect in a way that would be, to both of them, inexplicable.

In January 1763 an obscure old Catholic man died on a quiet farm twenty miles west of Dublin and was buried amid the sonorous cadences of Latin prayers, the opulent aroma of incense and a haze of smoke from guttering candles wafting around his coffin. Christopher Johnson had lived for seventy-nine years in the lush pastures of County Meath, most of them as a tenant of his wifes family. His public insignificance was not entirely a matter of choice. Throughout his adult life, people like him idolaters and potential traitors who looked kindly on the claims of exiled pretenders to the throne of Britain and Ireland were barred by law from public life, the professions and the armed forces. If he had ever aspired to glory, he had soon learned that such foolish dreams were incompatible with his place in history.

When he was still a child, his class of people the respectable, well-to-do native Catholics of Ireland had imagined for a while that their hour had come again, that the accession to the throne of Great Britain and Ireland of their co-religionist King James II heralded their resurrection. In what had seemed an almost miraculous deliverance, a Catholic king had been crowned and their hopes of being saved from oppression had been made flesh. They thought they would rise again and reclaim the lands and status that had been taken from them by the Protestant British colonists who had come to power in Ireland over the course of the seventeenth century. And then James had been deposed in a British coup and replaced by his impeccably Protestant daughter Mary and her husband William of Orange. For the last time, two men who had been crowned King of Britain fought a civil war for the throne, and this time Ireland was the battlefield.

As a little boy, Christopher Johnson had watched his older kinsmen ride out in all their pride and hope to fight in grand battles for King James, one of them on the River Boyne near his home. He had watched them ride back again in tatters from bloody disasters or from captivity, and the Jacobite cause gradually subside into a broken dream. He had learned how to live with the slow death of a defeated culture, how to keep his head down, how to hold his tongue, how to move amid undercurrents, how to survive. That he died at such a late age, and in such comfortable obscurity, was a testament to his mastery of those lessons.

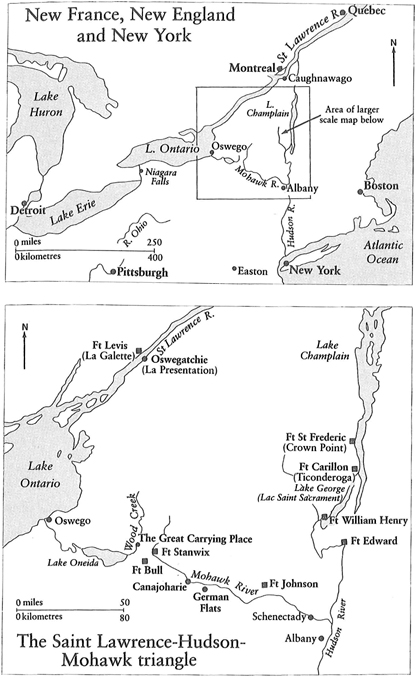

Christopher Johnsons death was of no concern to anyone in Ireland beyond his family and his neighbours; but 2,000 miles away, across the vast Atlantic and through the dense forests of upstate New York, the word spread and was heard with great solemnity. It eventually reached Lake Oneida, about twenty miles north of present-day Syracuse, and the Tuscarora village at Oquaga, which was off the usual track along which messages travelled through the territories of the Iroquois nations.

In early June 1763, after a journey eastwards of about 100 miles, six young warriors from the village arrived at the grand new house of Christopher Johnsons son William about halfway between Albany and Utica, in the present-day city of Johnstown. They were gauche and nervous, hoping that they could remember the proper ceremony that would convey their condolences on the death of Christopher Johnson. Having fortified themselves with a dram of rum and a pipe of tobacco, they formally addressed William Johnson and asked for his forgiveness, as we are but Youngsters, for any mistakes which for want of knowledge we may make.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «White Savage: William Johnson and the Invention of America»

Look at similar books to White Savage: William Johnson and the Invention of America. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book White Savage: William Johnson and the Invention of America and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.