Contents

Landmarks

Print Page List

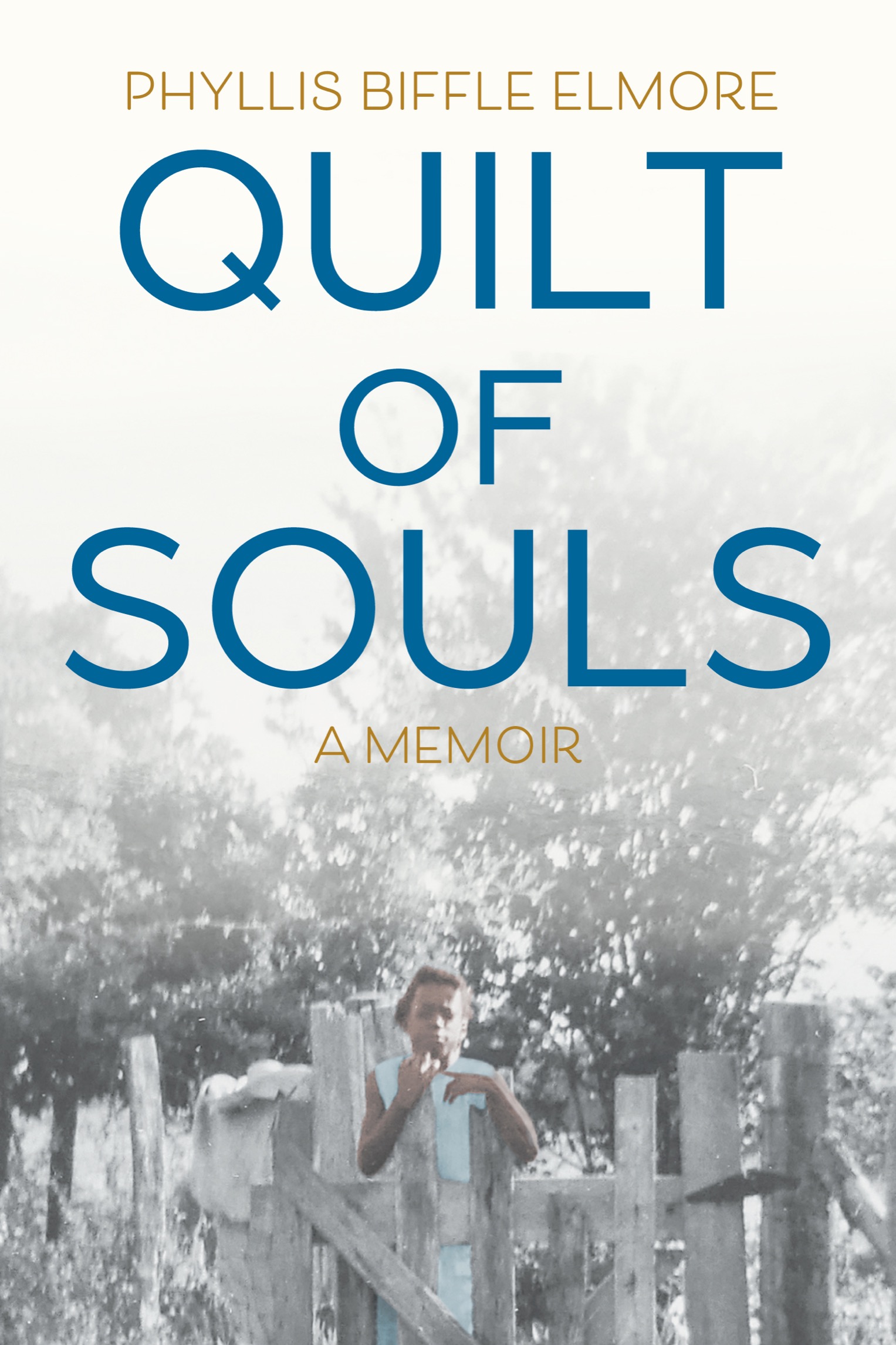

Copyright 2022 by Phyllis Biffle Elmore

All rights reserved, including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form. Charlesbridge and colophon are registered trademarks of Charlesbridge Publishing, Inc.

At the time of publication, all URLs printed in this book were accurate and active. Charlesbridge and the author are not responsible for the content or accessibility of any website.

An Imagine Book

Published by Charlesbridge

9 Galen Street

Watertown, MA 02472

(617) 926-0329

www.imaginebooks.net

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Elmore, Phyllis Biffle, author.

Title: Quilt of souls: a memoir / by Phyllis Biffle Elmore.

Description: [Watertown, Massachusetts]: Charlesbridge Publishing, [2022] | Summary: A memoir of a Detroit child raised in Alabama by her grandmother, whose storytelling and quilt-making open up a world of drama, passion, and African American identity.Provided by publisher.

Identifiers: LCCN 2022002561 (print) | LCCN 2022002562 (ebook) | ISBN 9781623545161 (hardback) | ISBN 9781632892430 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Elmore, Phyllis Biffle. | African American WomenAlabamaBiography. | Grandparent and child.

Classification: LCC E185.97.E47 A3 2022 (print) | LCC E185.97.E47 (ebook) | DDC 305.48/896073092 [B]dc23/eng/20220222

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2022002561

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2022002562

Ebook ISBN9781632892430

Production supervision by Jennifer Most Delaney

Cover design by Nicole Turner

Ebook design adapted from print design by Mira Kennedy

All photographs are included courtesy of the author

a_prh_6.0_141688262_c0_r1

For my grandmother, Lula Young Horn,

and the unsung women of her era

In memory of Rufus Biffle Jr.

and McCullah Biffle

And to Joean Henry, with love

Contents

Introduction

T he day I was taken from my home and driven sixteen hours down a road in a car filled with strangers, to a house in the middle of nowhere, to be delivered to grandparents Id never met, I felt alone, abandoned, angry, and very scared. It was 1957. I was four years old. The stigma of being given away would follow me for years, like a lost puppy nipping at my heels. It took my grandmother Lulas love and a tattered, centuries-old quilt to bring about my healing.

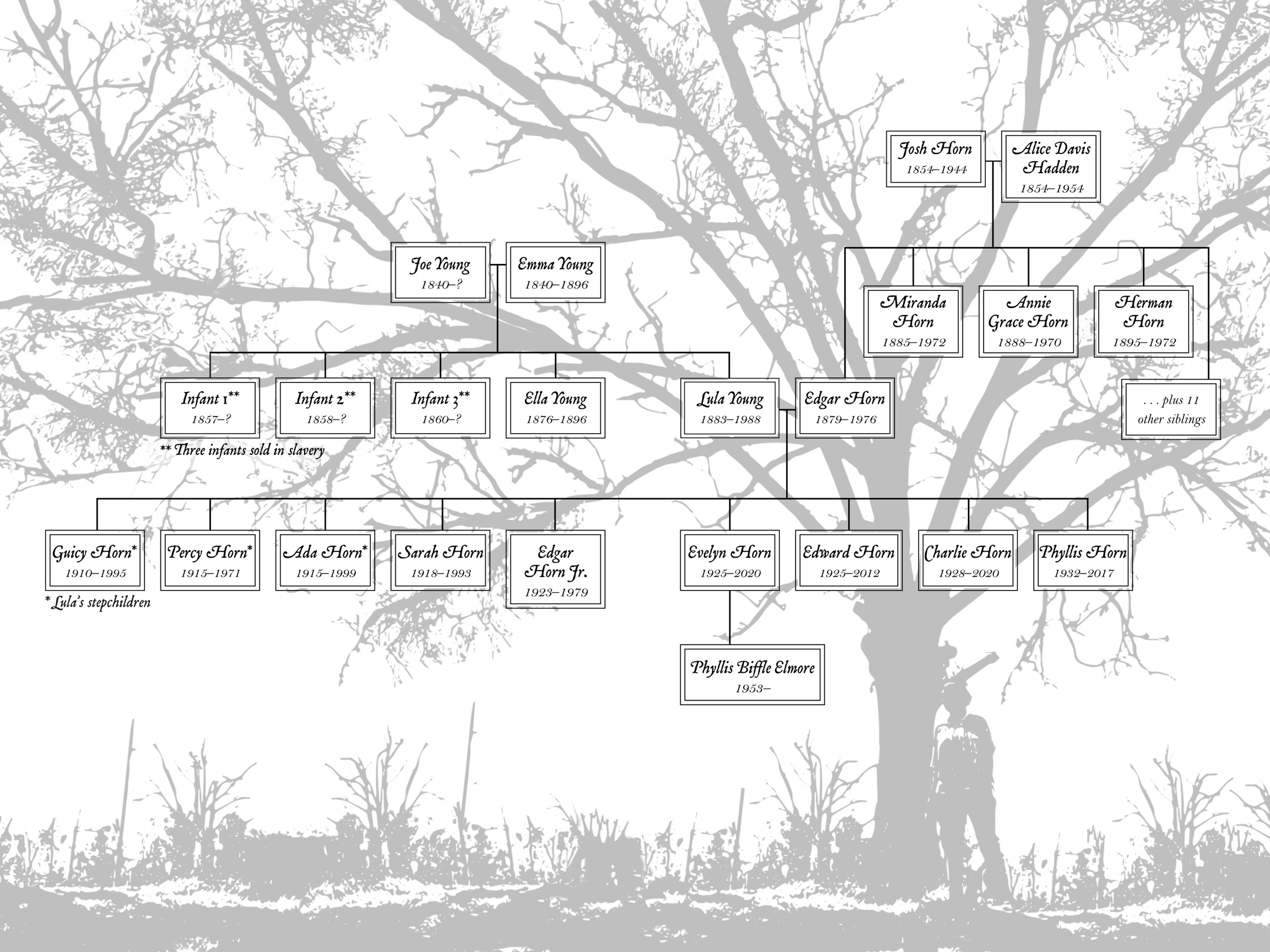

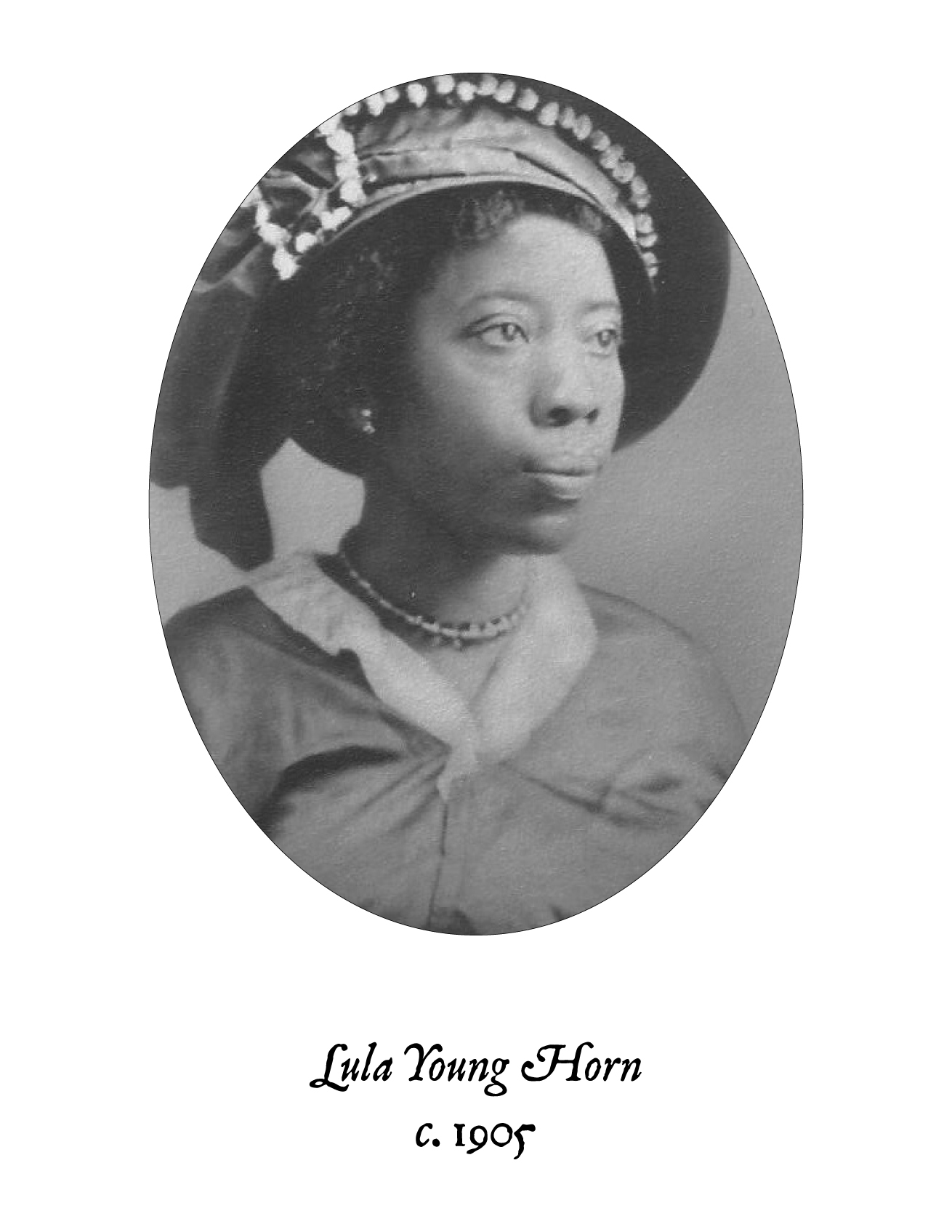

Lula Young Horn was born in the small town of Sandersville, Mississippi, in 1883. She grew up on the Young plantation, in an environment that sat heavy under the shadow of slavery, and she was destined to quilt. In quilting and in life, she was the catalyst of my upbringing. As she worked, she told me stories of the women who wore or were connected to the strips of fabric she wove into the hand-sewn quilts I would later name quilts of souls. It is a powerful title, for her quilts hold the consciousness of a long-ago generation. These women had no voice until my grandma gave them one.

During the nine years I lived in Alabama, many elderly women who resided nearby, born around the time of the Civil War and during the years of Reconstruction, became part of my extended family. They were an extension of my grandmothers life and represented all she believed in. She felt their stories were as relevant as hers, and I connected with these women too. Collectively, they were instrumental in preparing me to overcome so many obstacles. They tilled the soil of my resilience and, along with my grandmother, built within me a solid foundation as I prepared to face an uncertain future.

All these women are embodied inside of me.

African American quilting has long been an enigma for scholars and historians. It is a tradition older than the history of America itself, originating in Africa long before the first ships carrying slaves arrived in the Americas. Before and after the Civil War, African American women used scraps of clothing from white households to make bed coverings for both themselves and their slave-owners. Enslaved women also made quilts that were guides for escaping slaves. These quilts were hung on gates and clotheslines across the South. The patterns embedded in them showed slaves the way to freedom and included stars, railroad tracks, trees, and midnight-blue patches that represented river crossings, all coded symbols pointing the way north.

For many years, Grandma took the clothes of those whod passed on and turned them into quilts, which were both a source of warmth on cold nights and family heirlooms to be preserved for future generations. Many of my grandmothers quilts also used railroad crossing designs, in a wide range of colors. In all likelihood, this pattern was passed down from my great-grandmother, Emma Young, who was born into slavery in Mississippi around 1840.

Ill always be grateful to my grandmother, who gave me the opportunity to listen to her first-person tales of quilting, stories that reached far back into my maternal lineage. Grandmas quilts laid the foundation for future quilters, too, who now use some of the same patterns and skills my grandmother displayed. Quilting has become one of the most popular international hobbies of our time. Modern quilters have established quilt making as an art form, and their work is showcased in museums, quilting shows, and quilting guilds across the country. These new-wave quilts are visual works of art calling for social change, a way to bring attention to racial injustice and to galvanize communities to action. They are not designed to be placed at the foot of a bed or snuggled under on wintry nights. Instead, they have evolved into magnificent pieces of fabric aptly referred to as fiber or textile art.

In many ways, these quilts carry the same messages embedded in those sewn before and during Reconstruction. Current quilters, however, have the freedom to use their quilts as a way of raising awareness of inequality. They can address injustice without fear of reprisal, unlike the women of my grandmothers time. Lula Horns quilts of souls were also art, but she worked in a quieter tradition and a far different atmosphere from the present days.

I may have forgotten the first time I rode a bike, received my first kiss, or got my drivers license, but I will never forget Grandmas quilts of souls stories or the elderly women I met growing up in the rural South. The vast amount of history conveyed to me by my grandma and these women, all of whom were born while the ink was still drying on the Emancipation Proclamation, fascinated and intrigued me. Barefoot, Id run along the sandy roads, under the tall Alabama pines, and return to lie in the cool dirt under my grandparents house and listen to the conversation of the folks gathered in our front yard. Through their colloquy I gained knowledge, strength, purpose, and the grit Id rely on to sustain me in adulthood.