Phyllis Granoff - The Journey: Stories by K.C. Das

Here you can read online Phyllis Granoff - The Journey: Stories by K.C. Das full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2000, publisher: University of Michigan Center for South Asian Studies, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The Journey: Stories by K.C. Das

- Author:

- Publisher:University of Michigan Center for South Asian Studies

- Genre:

- Year:2000

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Journey: Stories by K.C. Das: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Journey: Stories by K.C. Das" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The Journey: Stories by K.C. Das — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Journey: Stories by K.C. Das" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

The Journey: Stories by K.C. Das

Translated by Phyllis Granoff

Michigan Papers on South and Southeast Asia Number 48

THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN CENTERS FOR SOUTH AND SOUTHEAST ASIAN STUDIES

Open access edition funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities/Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book Program.

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 00-102495

ISBN : 0-89148-081-1

Copyright @ 2000

by

Centers for South and Southeast Asian Studies

The University of Michigan

Printed in the United States of America

ISBN 978-0-89148-081-5 (paper)

ISBN 978-0-472-12831-0 (ebook)

ISBN 978-0-472-90231-6 (open access)

The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

This book is dedicated to the memory of all those who lost their lives in the cyclone of 1999 in Orissa and to the courage of those who came to their aid.

All royalties from the sale of this book will go to them.

Contents

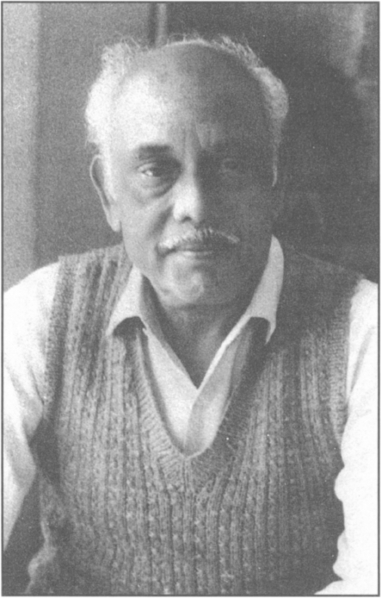

Kishori Charan Das

1

The Setting: Oriya Literature

K ishori Charan Das is deservedly one of the most celebrated writers in India today. He writes primarily in Oriya, the language of his native state of Orissa. Orissa is bordered on the north by Bihar and Bengal and on the south by the state of Andhra Pradesh. To the east is the Bay of Bengal. Orissa is perhaps best known for the famous temples at Bhuvaneshvara, Konarak, and Puri. A 1991 census counted approximately thirty-two million speakers of Oriya.

Historically, writing in vernacular languages in India had posed something of a challenge to the elite and orthodox literary culture of Indias classical language, Sanskrit. Only the so-called heterodox religious groups, the Buddhists and Jains, accepted and encouraged writing in a vernacular language. Both Buddhists and Jains used early vernaculars, called Middle Indic, for religious texts and secular compositions. For all others in early and medieval India, Sanskrit was considered to be the only proper language for the educated and the only language in which to write serious literature or discuss philosophy. The New Indic vernacular literatures, ancestors of todays languages, made their appearance at different times on the subcontinent. Oriya literature is said to have begun in the fifteenth century C.E. with an Oriya version of the great Sanskrit epic, the Mahabharata, by Sarala Das. For the next three hundred years, writing in Oriya was with few exceptions in verse and its subject matter was predominantly religious. In the sixteenth century, the translation of the Mahabharata was followed by a translation into Oriya of the other major Sanskrit epic, the Ramayana, by Balarama Dasa. At about the same time, Jagannatha Dasa rendered the important Sanskrit Vaishnava devotional text, the Bhagavata Purana, into Oriya. Balarama Dasa and Jagannatha Dasa are both known as members of a group of five poets, the Panca Sakha, who espoused a form of the Vaishnava faith that is unique to Orissa. All of these poets wrote about the god Vishnu, specifically in his form as the god Jagannatha, Lord of the World, who resides in the temple at Puri, Orissas most famous pilgrimage site. To this group of five Vaishnava poets are ascribed a number of hymns to Vishnu and a number of short philosophical texts, often abstruse and difficult to understand. The philosophical texts, also in verse, deal with such diverse topics as the creation of the world, the nature of God, and predictions of the future. They also include details about rituals to be performed and mantras to be recited. The Vaishnavism of the Panca Sakha poets was an esoteric tradition that had been heavily influenced by Tantric Buddhism. Its practice centered around yogic control of the breath and recitation of the divine names. Although some of the poetry of the Panca Sakha poets is still widely recited, the transmission of the esoteric teachings has not been maintained.

When we consider the origins of prose writing in Oriya, we are not surprised to find that, as is the case with other vernacular languages in India, prose compositions in Oriya appeared long after the development of its rich poetic tradition. Early prose compositions often imitated the complex syntax and rhetorical devices of the Sanskrit court romance, itself a highly artificial literary creation. Colloquial prose writing had existed in Sanskrit in medieval times and there had been a lively tradition of storytelling in colloquial Sanskrit and Middle Indic, particularly among the Jains. Nonetheless, outside these heterodox circles medieval authors seemed surprisingly reluctant to exploit the potential of the colloquial spoken language as a medium for literary prose. This reluctance carried over into modern times, so much so that historians of modern literatures can often point to a particular author or literary work, usually belonging to the end of the nineteenth century, as the start of a given vernacular prose literature. For Oriya, the founding figure is Fakir Mohan Senapati (1843-1918), who is generally considered to be the father of Oriya prose writing in general and the originator of the Oriya short story.

In their introduction to their translations of some of Fakir Mohans short stories, Leelawati and K. K. Mohapatra discuss his deep commitment to the Oriya language (Fakir Mohan Senapati: Selected Stories [New Delhi: Indus, 1995]). In Fakir Mohans day, there were certain interest groups that wished to convince British administrators that Oriya was nothing more than a dialect of Bengali. Fakir Mohan was determined that Oriya be recognized as a language in its own right, with its own unique creative potential. One of his first steps was to write mathematics, geography, and history textbooks in Oriya for schoolchildren, so that they could learn in their own language and would not have to rely on books written in Bengali. In 1868, he founded a printing establishment for Oriya writing, from which he published an Oriya literary magazine and a newsletter. It would be almost thirty years before he began writing the novels and short stories that today are considered to be the beginnings of Oriya prose literature.

Kishori Charan Das has written a brief history of Oriya prose fiction in his English introduction to a collection of translations of Oriya stories, Beyond the Roots: An Anthology of Oriya Short Stories (Delhi: National Book Trust, 1996). He has also written an essay on the subject in Oriya, Shatabdir Kaladrishti: Kshudragalpa (The Artistic Vision of the Last Century: The Short Story); it was recently published in a festschrift presented to K. C. Das on the occasion of his seventy-fifth birthday (Gadyashilpi Kishoricarana, Abhinandana Grantha [Bhuvaneshvara: Bholanath Press, 1999]). In both of these essays, as he traces the history of the modern Oriya short story, K. C. Das emphasizes the debt that Oriya literature owes to Fakir Mohan. Fakir Mohan was the first to use the everyday language of the village in his stories; his writing also showed a profound consciousness of the role that literature can play as an instrument of social change by exposing injustices in society.

K. C. Das focuses on one story in particular, Rebati, which has been translated by the Mohapatras in their collection of Fakir Mohans stories. Das sees in Fakir Mohan, and particularly in this one story, the promise of much that was to come in Oriya literature. Rebati is a seemingly simple tale of a village girl whose father breaks with tradition and allows her to learn to read and write. The family is wiped out by cholera, leaving only the old grandmother, who hurls abuse at Rebati, blaming her unwomanly desire to be literate for the familys misfortunes. Das considers Rebati a fully developed short story despite the fact that in his estimation it is the first real short story in Oriya. Perhaps its greatest achievement for Das is its tone, at once compassionate and ironic. The story concludes with the ignorant grandmothers imprecations, which Das feels evoke not only sorrow and anger in the reader but also a bitter smile in response to what he calls in English Fakir Mohans black humor. As we shall see, Dass stories often have their own black humor; in many of them, he, too, achieves a striking blend of these two otherwise discordant moods: compassion and irony.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The Journey: Stories by K.C. Das»

Look at similar books to The Journey: Stories by K.C. Das. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Journey: Stories by K.C. Das and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.