Phyllis Granoff received a Ph.D from Harvard University in Sanskrit and Indian Studies and Fine Arts in 1973. She teaches Sanskrit and Indian Religions at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario. Her first book, Philosophy and Argument in Late Vedanta: Sri Harsas Khandanakhandakhadya, was first published by D. Reidel in 1978. She has written extensively on Jain literature, particularly Jain religious biographies. In 1992 she published Speaking of Monks: Religious Biography in India and China, co-authored with her husband Koichi Shinohara (Mosaic Press). She has also translated a collection of short stories by Bibhutibhushan Bandhopadhyaya (A Strange Attachment, Mosaic Press, 1982) from Bengali to English. She currently edits the Journal of Indian Philosophy and continues to work on traditional and modern Indian literature.

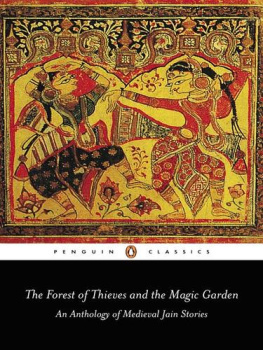

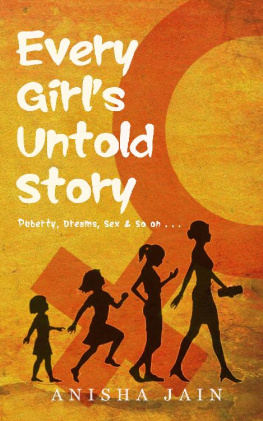

THE FOREST OF THIEVES

AND THE MAGIC GARDEN

An Anthology of Medieval

Jain Stories

Selected, translated and with an introduction by

Phyllis Granoff

PENGUIN BOOKS

In honour of my mother Dorothy Granoff

and

in memory of my mother-in-law Masako Shinohara

CONTENTS

TRANSLATORS NOTE

My chief purpose in translating selections from this rich literature was to bring it to the attention of a new audience, those who knew little or nothing of it before. This led me to several choices in the translations. Firstly, I wanted the result to read as naturally as possible and therefore did not aim for a literal translation. At the same time, I hoped that I might preserve something of the flavor of the original, where those two aims were not entirely incompatible. I occasionally, supplied information in the story that an educated reader of the time might well have been expected to know. For example, when the story said that someone accepted the vows of a householder, I listed the vows individually although they were not listed in the story itself. Occasionally I even supplied a line of context, where a story formed part of a larger unit and the translation began in the middle, so to speak. In other stories I tried to help the reader by providing background information about characters in the story and their relationship to each other. Thus in the section about Rma and Lakmaa, which contains a summary of the Rmyaa plot, I added some identifying marks for the various characters mentioned, explaining who they were and in some cases what they had done. In some instances I did not translate technical terms as technical terms, fearing that the subtleties would be lost on a general reader. For example, I simply glossed the type of knowledge that a demi-god has as supernatural knowledge, rather than supplying a technical term. In other cases, in an effort not to encumber my translations with too many foreign terms, I omitted the names of heavens and different realms of gods and simply translated the basic fact that so-and-so was reborn as a god. I also did not try to standardize terms, but relied more on the flow of the prose.

Where stories contained both verse and prose, I initially tried to retain some of the distinctiveness of the style by indenting what was verse in the original, hoping to indicate in that way that the original combined both poetry and prose. In the final editing, much of this was edited out. In all cases, I gave prose translations of the verses. I laboured to unpack the puns and plays on words that are so important to the traditional Indian poet and writer of prose. Translators over the years have done many different things with these plays on words, which are so easily made in Sanskrit and its closely related vernacular languages and so utterly impossible in English. Some translators choose to render one meaning in the translated text and put the second in footnotes, explaining how the original yields both meanings. I did not want to burden these stories with footnotes, and so I tried to put both meanings into the translation. What is lost, of course, is the playfulness and challenge that these puns bring to a text. These are only some of the choices I eventually made; I hope that the gains in readability will make up for any loss in exactitude.

INTRODUCTION

Blessed One, how can I make my way safely through the forest that is the cycle of rebirths? And once I cross the forest, where will I be? The monk replied, Listen. There are two forests; one is the forest that exists outside us, in nature, and the other is the forest that is within us, the tangle of our thoughts and desires. Let me use the forest that exists in nature as a parable to teach you of that other, equally treacherous forest. Imagine there was a merchant, who wanted to go from one city to another. He announces to all and sundry, I seek someone to accompany me to the city such and such; I will make sure that no harm befalls him on the journey, as long as he follows my advice. When they hear this announcment many merchants hasten to join him. Before they depart, the merchant describes to them the conditions of the road that they must travel. My friends, my travelling companions! he begins. There are two paths to choose from; one is straight, but the other is somewhat tortuous. Believe it or not, it is easier to follow the crooked path; eventually it leads one onto the straight way and to the city we seek. The straight path is harder to travel. Although it leads to the goal more quickly, it is dangerous and arduous. For as soon as one enters the straight path there lie in wait for him terrifying creatures, lions and tigers, that obstruct his way to the city he seeks. They pursue him until he reaches the city that is the object of his desires. They kill the person who steps off the path even for a moment, but they cannot harm the one who keeps to the right road.

Here is the explanation for the parable. The merchant is the Noble Jina, honored by gods and anti-gods, the crest jewel of the universe. His proclamation is his teaching of the Jain doctrine, through various techniques, telling stories that attract the listener to the Jain doctrine and turn the listener away from false doctrines; telling stories that cause the listener to feel disgust for worldly existence and delight in the religious life. The travellers are the souls who set out for the city of Liberation, making their way across the forest of transmigratory existence. The forest is the entire cycle of rebirths, which includes births in hell, as animals, humans and gods. The straight path is the way of the renunciate; the path that is slightly crooked is the way of the lay practitioner. In the end it leads onto the path of renunciation The city that is the object of the travellers desires is the city of peace, of final release, which is devoid of the torments of birth, old age, death, disease, grief and the like. The tigers and lions are the destructive passions such as lust, pride, greed, delusion, and anger, all of which are obstructions to the attainment of Liberation.