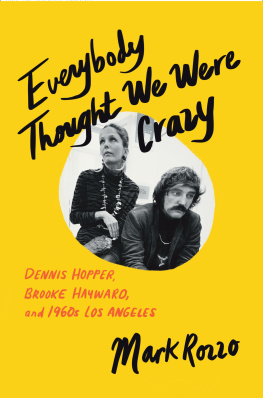

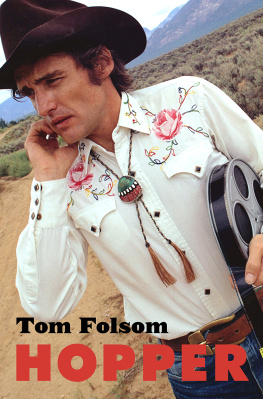

Dennis Hopper/Hopper Art Trust.

For Valeria and Ines and Cecilia

And love comes in at the eye;

Thats all we shall know for truth

Before we grow old and die.

WILLIAM BUTLER YEATS, A DRINKING SONG

Live not for others but affect thyself

from thy enhanced interiorbelieving what thou carry.

MICHAEL M C CLURE, GHOST TANTRA 49

Contents

I n the fall of 1961, Brooke Hayward was coming down with a case of what she called the Transcontinental Blues. The air of Los Angeles turned brittle as the humidity level descended toward zero. The Santa Ana winds were rasping and harsh. A drought made the Santa Monica Mountains and Bel Air canyons tinder dry. It was the season, as Joan Didion would later write, of suicide and divorce and prickly dread.

Pleased though she was about her recent shoot for Life magazine and her first appearance in a feature film, Mad Dog Coll, Brooke felt like an exile. I missed the seasons, New York City, my apartment overlooking the planetarium, the theater, museums, friends, she recalled. In particular, she missed her father, who loathed LA almost as much as he loathed his daughters new husband. He was enraged by the couples move to the West Coast, just as hed been by their hasty wedding in New York three months before. The tense emotional dtente between father and daughter would endure for years. Brooke also missed her little sister. October 18 marked a full year since her death. Now the second anniversary of the death of her mother was approaching, too.

It was just around Halloween that her new husband vanished. Brooke called all over town, but no one had seen him, or, if they had, they werent telling. On the topic of marriage, he had once said, I wont be easy to live with. I go off on strange tangents. Why, I might not even come home for three days. Three days stretched to a week, and there was still no sign of him. It pained Brooke, sitting in their little rental house at the top of Stone Canyon Road in Bel Air, to admit to herself that her father had been rightthis man was pure trouble. She decided to move back to New York with Jeffrey and Willie, her toddler sons from her first marriage, and write this second marriage off. It was a disaster.

Her missing husband was Dennis Hopper, a fellow actor who had become a teenage movie star in the 1950s after he had appeared in Rebel Without a Cause and Giant. Dennis had a reputation for waywardness, and Brooke never would solve the mystery of his whereabouts that week. But one hot night in early November, under a moonless sky and with the Santa Anas whipping through the eucalyptus trees, Dennis slipped back into the house and got into bed next to Brooke. She pretended not to notice. Shed let him have it in the morning.

Brooke never had the chance. That Monday morning, November 6, a fire reared up in a patch of resinous brush north of Mulholland Drive. Driven by fifty-mile-an-hour gusts, the flames refused to be contained. Brooke was readying the boys for school when she saw a pair of fire trucks racing up Stone Canyon Road. While her husband slept, she watched the man across the street run out of his house and stand there, looking up toward Mulholland Drive through binoculars. He started loading his station wagon. Brooke shook Dennis awake. He opened his eyes to find a scene that was already tipping toward chaos.

SHE : Ill come back and get you!

HE : We gotta save something!

Brooke hurried Jeffrey and Willie into the car for their daily ride to the John Thomas Dye School on Chalon Road. They would be safer there. Dennis grabbed a Milton Avery paintinga reclining nude that had belonged to Brookes parentsoff a wall and, as Brooke was about to pull out of the drive, threw it into the car. I thought he was nuts, Brooke remembered.

There was no time to save the Chinese tapestries that Denniss father had given them or the books or the photo albums or the toys. What ensued was a day of surreal hell scenes, as the Bel Air Fire came roaring down the canyon roadsStradella, Roscomare, Stone Canyonon its way to consuming more than six thousand acres in the most destructive conflagration in the regions history. Burning shingles lofted through the air, picture windows crumbled, and carbonized patio furniture floated in swimming pools. Low-flying B-17s buzzed overhead in a rust-orange sky, dropping borate solution. Nearly every fire department in the city was dispatched to Bel Air, as the flames climbed fifty feet and the fire jumped from house to house, from road to road, from canyon to canyon. It swept across Bel Air and Brentwood, incinerating everything in its path at a rate of thirteen acres per minute, reaching as far west as Topanga Canyon. The fire departments official report described it as a hurricane of fire.

The familys accounts of that traumatic morning are a Gordian knot of conflicting recollections, oft-told stories, and smeared impressions formed amid the chaos that was building on Stone Canyon Road. In the course of the day, Brooke drove through corridors of flame to retrieve the boys and return to Stone Canyon, while Dennis set out on foot, pulling obstinant neighbors out of their burning houses as he made his way down the hill toward Sunset Boulevard. When Brooke made it back to Stone Canyon, she found the scorched street closed to traffic. Her husband was nowhere in sight.

In Nathanael Wests novel The Day of the Locust, a painter toils day and night on an apocalyptic canvas called The Burning of Los Angeles. The Bel Air Fire made that cataclysmic vision real. It was responsible for the most devastating property losses in California since the 1906 San Francisco earthquake. And it was responsible for the destruction of Brooke and Denniss house at the top of Stone Canyon, among the first of nearly five hundred houses to burn that day.

IF YOU WERE A BELIEVER in omens, it was not the most auspicious beginning for a marriage. But Brooke Hayward and Dennis Hopper, one an ingenue on the upswing and the other a self-sabotaging hard case, were soon to become, as one chronicler noted, the coolest kids in Hollywood. Theirs was destined to be the emblematic love story of 1960s Los Angeles, that golden epoch of postwar California at its sunny apex. They were the prime catalysts and connectors during a brief, kaleidoscopic cultural moment when Hollywood upstarts, art-world superstars, and the emerging shaggy aristocracy of rock rubbed up against one another and threw off sparks. The concurrent revolutionary ferment in art, music, and movies made the city of Los Angeles, so often dismissed as a frontier backwater, into a cultural force. Brooke and Dennis, more than anyone else, connected those realms. It was a great time to be in Los Angeles, Brooke said. No more Transcontinental Blues.

Beginning anew after the Bel Air Fire, the household they created on North Crescent Heights Boulevard, a sinuous byway in the Hollywood Hills above the Sunset Strip, became the repository of one of the eras greatest private collections of contemporary art: Lichtensteins and Warhols, Stellas and Ruschas, Rauschenbergs and Kienholzes, even one of the last pieces that Marcel Duchamp, the twentieth centurys provocateur in chief, would ever create. The house was an art piece itself, the so-called Prado of Pop, in which Brookes design experiments and Denniss eye for paintings, sculptures, and assemblages created an environment that left an indelible mark on everyone who stepped into it.

Jane Fonda, Brookes best friend growing up, called it a magical house. For Joan Didion, it was a place of such gaiety and wit that it seems the result of some marvellous scavenger hunt. Andy Warhol loved it and compared it to an amusement park. When Michael Nesmith, a guitar-picking cast member on