This edition is published by Papamoa Press www.pp-publishing.com

To join our mailing list for new titles or for issues with our books papamoapress@gmail.com

Or on Facebook

Text originally published in 1961 under the same title.

Papamoa Press 2018, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

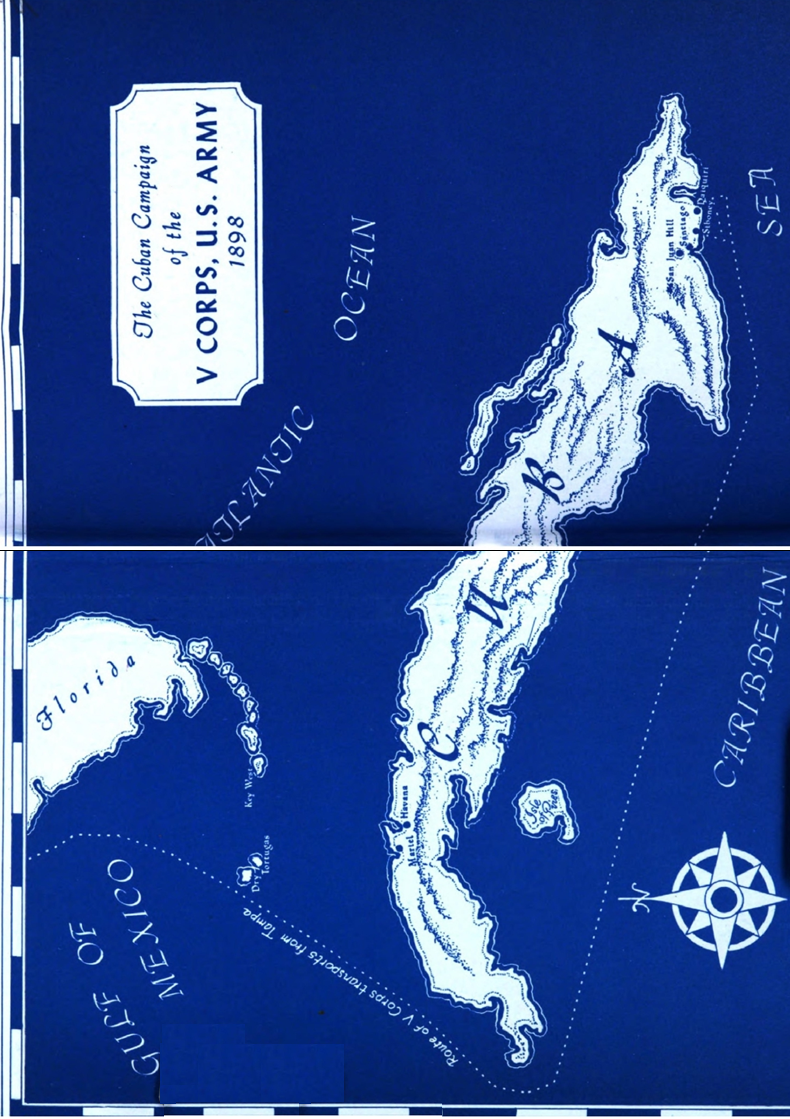

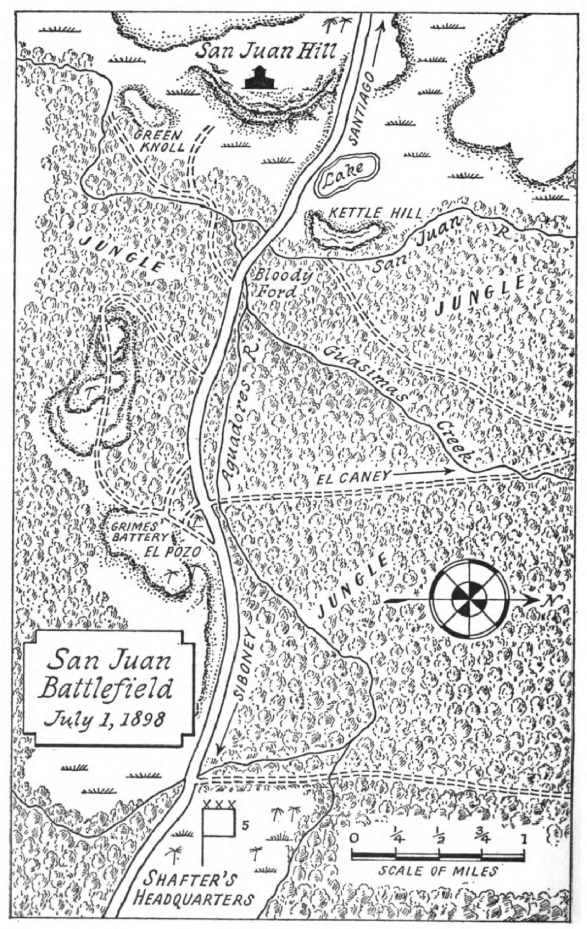

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

CHARGE!

THE STORY OF THE BATTLE OF SAN JUAN HILL

BY

A. C. M. AZOY

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ATTENTION!

ON JULY 1, 1898, the United States Army fought an unusual battle.

It was the final and decisive engagement of a three-round fight that began modestly enough with a regimental set-to, later went on to a divisional encounter, and then ended with a slam-bang, full-scale assault on hostile positions by an Army Corps, concluding in a head-on charge that won the day.

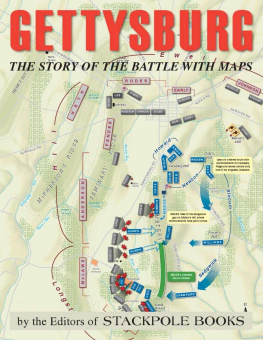

Compared to the famous affair of Gettysburg on the thirty-fifth anniversary of which it occurred, it was little more than an outpost action, and World War veterans would disdainfully rank it as not much better than a good-sized commando fracas. But it holds a record as the only engagement in our Armys history which marked the simultaneous start and finish of a campaign by an expeditionary force on foreign soil. Furthermore, it wasand still isone of the extremely rare examples in any armys history of an outnumbered command of infantry and artillery storming and capturing the permanent fortifications of a foe who was better positioned on his own home grounds, better armed and equipped, better trained for the work at hand, better acclimated to the fighting conditions and in point of fact superior in just about everything but the will to win. Its bullet-riddled hours saw our first use of smokeless powder and the last battlefield appearance of flashing sabers and waving banners, bestowed the Medal of Honor on a valorous total of twenty-six nephews of Uncle Sam, broke Spains centuries-old empire to make a republic of her colony of Cuba, gained recognition of the United States as a new world power, set a future president on his way to the White House, and incidentally taught thousands of Americans the correct pronunciation of the Spanish j. History calls this fight of that long-ago Cuban campaign the charge up San Juan Hill; cynical war correspondents caustically referred to it as comic opera, but the troops who sweated through it and saw their buddies (they called them bunkies then) killed and woundedjust as surely as more scientific methods of mass mayhem later would provide the casualty lists at Soissons and Bastogne and Iwo Jimaprofanely proclaimed the battle the whole Spanish-American War. And they were just about right.

This is the story of that battle.

SALUTE!

The helpful and valuable co-operation is most gratefully acknowledged of: Thelma E. Bedell, Chief of Readers Service, U.S. Military Academy Library; Olga J. Carney; Sidney Forman, Librarian, U.S. Military Academy; Major-General Philip E. Gallagher, U.S. Army (Ret); Sylvia C. Hilton, Librarian, New York Society Library; Dr. Francis S. Ronalds, U.S. Department of the Interior; Middleton Rose, late Sergeant, K Co., 7 th Regiment, N.Y. National Guard; Erwin H. Sherman, late Captain, 151 st Field Artillery, U.S. Army, and William B. Tippetts.

A.C.M.A.

DEDICATION

To the

ARMY OF THE UNITED STATES

Past, present, and future

HOW!

IREVEILLE[JANUARY 1APRIL 25]

OF ALL THE MIDNIGHT celebrations of December 31, 1897, welcoming the new year of 1898, nonenot even the holiday high jinks in the luxurious lobbies of New Yorks recently opened Waldorf-Astoriaaroused more enthusiastic gaiety than that offered by a man-of-war of the United States Navy, moored in lonely majesty in the harbor of Key West, at the very tip of Florida.

As the ships bell sounded the eight strokes that marked the last hour of the old year a boatswains pipe shrilled from the dark mass of the ironclad and on the instant strings of electric lights blazed into a dazzling outline of hull, funnels, masts, and rigging. The effect on the surprised onlookers of this sudden and undreamed-of spectacle was overwhelming. Salvos of applause, whistles, and cheers burst spontaneously from the watchers on the shore and the neighboring ships, and next day the local paper enthusiastically termed the show one of the finest displays of electricity ever witnessed in the city, or perhaps in the south. With such a splendid start, the Key West citizenry gaily assured each other, 1898 should indeed be a happy New Year for all.

But, as the year turned out, a less accurate symbol of happiness than the gleaming silhouette that shone so bravely there in the soft Florida night, or one more inappropriate to serve as an omen of peace and prosperity, would have been hard to find. For the ship was the U.S.S. Maine , destined in six short weeks to inspire and lend her name to a national call to arms.

For a month the Maine had idly swung at her harbor buoy, her white hull and buff superstructure dominating the local seascape. By day her crew could be seen busy at drill and assorted tasks of marine housekeeping; by night her shore liberty parties were equally active in acquiring chronic indigestion from the fried pork and possum urged on them by the citys hospitable inhabitants, and everyone wondered why such a ship should be so long sequestered in a harbor that even the most rabid Key West booster would have to admit was a port of something less than national importance. Only the Maines commander, Captain Charles D. Sigsbee, knew the answer and that answer was in navy orders marked Confidential.

As a member of our North Atlantic Squadron under doughty old Admiral Sicard the Maine had spent the summer of 97 off the New England coast. Target practices and fleet maneuvers were pleasantly interspersed with visits to Newport, Bar Harbor, and other highly social ports of call that delightfully dulled the ugly rumors that with increasing frequency were drifting up from the Spanish island colony of Cuba, a paltry ninety miles or so from our southernmost coast. For more than two generations the Cuban colonists had been agitating for an autonomous status for their country. Over the years this agitation had taken various forms, ranging from passive resistance to a shooting war with all the trimmings of burned plantation houses, ruined crops, starving peasants, homeless refugees, and the killing of innocent bystanders. Now at last Spain was determined that the island unrest should be stopped once and for all, and to see that it was she sent over her most experienced pacifier, one General Weyler. His primitive pacification methods soon earned him the accurate but hardly affectionate nickname of Butcher and served to inflame still further the resentment which most Americans had long felt against Spains rough treatment of her Cuban subjects. Recruits for the Cuban insurrectos were secretly enlisted in the United States and spirited across the Caribbean; the single-starred Cuban flag was designed and first flown in New York City; guns and ammunition were smuggled from our shores to the Cuban insurgents by American filibusters whose descendants would, in years to come, smuggle rum in the opposite direction. Diplomatic relations between Uncle Sam and the Castilian crown were becoming decidedly strained, and when William Randolph Hearst of the New York Journal and Joseph Pulitzer of the New York World heedlessly seized upon the headline news possibilities inherent in this tenuous situation to promote the circulations of their rival sheets, official Washington was gravely apprehensive over what might happen. What did at last happen to cause the final rupture between the two countries could not have been less provoked nor more provoking.