Campaign 57

San Juan Hill 1898

Americas emergence as a world power

Angus Konstam Illustrated by David Rickman

Series editor Lee Johnson Consultant editor David G Chandler

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

L abelled a splendid little war by Senator John Hay, the Spanish American War was a strange event in US history, caused as much by the newspapers as by political events. In 1897, support for Cuban insurgents fighting for independence from Spain was widespread in the United States, and was fuelled by the yellow press in a bid to sell newspapers. When a journalist told William Randolph Hearst that there was no real war in Cuba, Hearst replied: You supply the story. Ill supply the war.

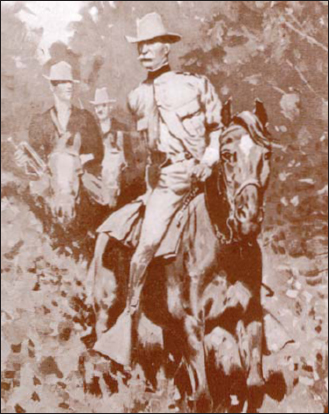

Gen. William R. Shafter, commander of the V Corps, the United States expeditionary force to Cuba. Obesity and fatigue prevented him taking an active part in the battle, and he was subsequently pilloried by both fellow officers and the press. (Library of Congress)

In early 1898 the USS Maine was sent from Key West to Havana to help protect US citizens in the city. At 9:40pm on 15 February the battleship was ripped apart by a massive explosion, which cost the lives of over 250 American sailors. A court of inquiry would later blame the disaster on the explosion of a mine under the ship. The Spanish were the likely culprits.

Over the next two months both sides mobilised their armed forces and called for volunteers. The US Congress voted for a war budget, and President McKinley demanded that Spain sign an armistice with the Cubans and allow the United States to mediate. The Spanish refused. Congress then passed a resolution backing Cuban independence, and Spain broke off diplomatic relations. On 21 April the US Navy left Key West to impose a blockade of Cuba. Spain therefore declared war, and the United States officially declared war in retaliation on 25 April 1898.

What followed was one of the strangest campaigns in military history, one of a number of unusual campaigns in the Pacific and the Caribbean. The Santiago campaign was fought by two armies who both seemed to defy military logic at every turn. The organisation and supply of the American army was reminiscent of the British in the Crimean War. For their part, the Spanish commanders were more alarmed by a few hundred guerrillas in the rear than by a large modern army advancing to its front. The battle of San Juan Hill, on 1 July 1898, was fought without direction, with decisions made by privates and junior officers setting the course of the battle. The farce continued over the following weeks, when surrender talks dragged on as both parties seemed more influenced by saving face and the reaction of the press than by the military situation. Teddy Roosevelt later called the campaign a bully affair. Bully was an apt term.

Gen. Joseph Fighting Joe Wheeler, commander of the Cavalry Division, US V Corps. A former Confederate general, Wheeler performed with evident skill and zeal during the campaign, despite his age and frailty. (Library of Congress)

Within months of the outbreak of war, the Spanish would lose their possessions in Cuba, the Philippines, Puerto Rico, Saipan and Guam. The war marked the end of Spanish sovereignty in her New World, and saw the establishment of the United States as a world power.

ORIGINS OF THE CAMPAIGN

F or over four centuries before 1898, Spain had ruled over a vast and profitable overseas empire, based on her Caribbean, Central and South American possessions. Although Mexico and Peru provided the greatest source of mineral wealth (i.e. gold and silver), Cuba was regarded as the linchpin of this empire, and Havana the most important harbour in the Americas. Foreign interlopers nibbled away at the Spanish Main, and following the involvement of Spain in the Napoleonic Wars (18081815) many New World provinces took the opportunity to seize independence. By 1860 only Cuba and Puerto Rico were left to remind the Spanish of their former glory in the Caribbean, and Cuba was causing severe problems for the government.

Seeds of unrest had spread throughout Cuba, and in 1868, Cuban insurgents launched the Ten Year War (186878), the First Cuban War of Independence. Although a military failure, it provided the base from which Cuban insurgents would launch an unremitting guerrilla war against the Spanish army of occupation, destroying sugar crops, disrupting transportation and attacking isolated troop outposts.

During the Ten Year War, American sympathy for the cause of the Cuban revolution grew, fuelled by atrocity stories in the press. The end of the war brought an uneasy peace, while exiled revolutionary leaders like Maximo Gomez, Antonio Maceo and Jos Marti plotted to renew the struggle. By 1895 they were ready, this time with the American press following their every move. The revolution got off to a bad start, however, and the key figures of Maceo and Marti were killed.

Maj.Gen. Henry W. Lawton, commander of the 2nd Division of Shafters V Corps. Pinned at El Caney, his command was unable to participate in the Battle of San Juan. Sketch by Frederic Remington. (Private Collection)

The Spanish appointed Gen. Weyler as Governor of Cuba, and his policies were singularly effective. A trocha (or fortified line) was dug, splitting the island in two. A reconcentrado policy forced the rural population into fortified villages, but the savagery of the war and resultant destruction of crops and animals led to mass starvation. This only provided fuel for the American press. By 1897 the insurgents were crushed everywhere but Santiago, but Weylers policies, though militarily sound, were a political disaster. He was replaced by the more lenient Gen. Blanco, but by that time the damage was done. With the American press and public at fever pitch, United States intervention seemed inevitable.

On 15 February 1898, the battleship USS Maine blew up in Havana harbour. For years, Spains attempt to regain colonial power against a rag-tag army of Cuban insurgents had been watched by the American public, whose sentiments had been inflamed by anti-Spanish bias in the press calling for the islands independence. Public feeling had been running so high that the issue was discussed in terms of Cuban independence or war. The mysterious disaster which overtook the USS Maine was a spark sufficient to ignite the fire of war, and on 25 April 1898 Congress declared that a state of war had existed between the USA and Spain since 21 April. Only three days earlier, Congress had passed a mobilisation act which represented a compromise between the National Guard enthusiasts and army reformers. It called for a force made up of regulars and volunteers, many of the latter supposedly being raised from men immune to tropical diseases, such as yellow fever. Since Spain was obviously incapable of invading the United States (apart from in the overwrought imagination of a few alarmists), and since Cuba could not be freed without direct intervention, a number of regiments organised as the V Corps were sent to the ill-equipped port of Tampa, Florida, for eventual embarkation to Cuba.