The Spanish-American War

The Spanish-American War

A Documentary History with Commentaries

Edited by Brad K. Berner

Foreword by Kalman Goldstein

FAIRLEIGH DICKINSON UNIVERSITY PRESS

Madison Teaneck

Published by Fairleigh Dickinson University Press

Copublished with Rowman & Littlefield

4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706

www.rowman.com

10 Thornbury Road, Plymouth PL6 7PP, United Kingdom

Copyright 2014 by Brad K. Berner

All rights reserved . No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

The Spanish-American war : a documentary history with commentaries / edited by Brad K. Berner ; foreword by Kalman Goldstein.

pages cm

ISBN 978-1-61147-574-6 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-61147-575-3 (ebook) 1. Spanish-American War, 1898Sources. I. Berner, Brad K., 1952 , editor of compilation.

E715.S77 2014

973.8'9dc23

2013049050

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

Printed in the United States of America

Acknowledgments

Extracts abridged from Always the Young Strangers by Carl Sandburg, copyright 1953, 1952 by Carl Sandburg and renewed 1981, 1980 by Margaret Sandburg, Helga Sandburg Crile and Janet Sandburg. Reprinted by permission of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company.

Thanks to Paul Schlueter for providing the bibliography to this volume and the index.

Foreword

The Spanish-American War has lately been even more neglected by historians than the War of 1812, but for different reasons. The War of 1812 was at first militarily humiliating and politically divisive; it temporarily destroyed our capital city and nearly bankrupted the country. Save for Jacksons victory at New Orleans, fought ironically after the peace treaty had been signed, there seemed little to celebrate or wish to remember. Only recently has historical interest once again been piqued, and American naval victories remembered. On the other hand, the Spanish-American War seemed at first so triumphal that it could be taken for granted. Our first war outside North America, aided in part by British encouragement, was quickly over with, inexpensive, and an unbroken series of overwhelming victories on two continents. After the peace, many Americans began to regret that we might have incurred more responsibilities than we were comfortable with. Save for Teddy Roosevelts chest-thumping and Progressive Era imperialists, triumphalism faded. Admiral Dewey, for one, was convinced that our victory might make a war with Germany necessary and embroil us in the global balance of power; he became a pioneer of preparedness agitation. At the least, the victory made obsolescent our stance of isolationism, whether we willed it or not. One can even make a case for our occupation of the Philippines putting us on an eventual collision course with Japanese expansionism over the Open Door Policy. So while certainly not embarrassing, the war was soon described as something we had stumbled into or had been manipulated into fighting. It would be followed by embroilment in the messy affairs of lesser peoples which would become more annoying than gratifying.

In this book, Berner has assembled a collection of documents relating to the war and its immediate aftermath from several points of view, not only the American and not simply that of the two governments or their military forces involved. There is indeed an unusually full focus on the Spanish experience and the extent to which its leaders fell into the war fatalistically.

They expected to lose to a superior force but hoped to save face and honor at home while keeping power by maneuvering around a series of domestic crises, never suspecting that we would denude them of so many of their overseas possessions. Spains Liberal government was under pressure not only from rival Conservatives (party names, not ideological descriptions), but by the Queen Regent, Carlists who supported a pretender to the crown, a clamorous socialist movement, and endemic regional disturbances. It would have to put down riots and declare martial law against the Catalans. Colonial independence movements and American pressures were the least of the nations dilemmas.

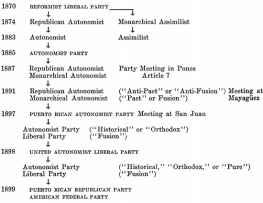

Most accounts or documentary collections of the Filipino situation give adequate space to Emilio Aguinaldos leadership of the movement for Philippine independence and his betrayal by American interventionist forces, which he first mistook for liberators. This would lead to many years of guerrilla warfare both in Luzon and in the outlying islands. Berner illuminates the Filipinos autonomous political development, their own struggle to create a constitution and government while the Americans were invading Manila, and contributions by figures central to Philippine history but relatively ignored in American accounts: Andrs Bonifacio, Apolinario Mabini, Felipe Agoncillo, and Jos Alejandrino. Similarly with Puerto Rico, Berner cites a number of opinions and stances regarding our occupation and intentions, by Ramn Betances, Eugene Hostos, and above all Luis Muoz Rivera.

On the American side, there are well-known and vital selections from the press, by expansionist U.S. Senators Henry Cabot Lodge and Albert Beveridge, Teddy Roosevelt and Admiral Dewey, but these documents play almost second fiddle to significant and prophetic comments from unexpected sources. For example, Carl Sandburg served both in Cuba and Puerto Rico, so there are little-known but evocative excerpts from his accounts. Moreover, Berner has discovered a generous number of angry letters from African-American soldiers and editorials from African-American clergy and newspaper publishers about the treatment of colored troopers. Diary entries by soldiers fighting in a Jim Crow army in Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines, with white troops who referred to both them and the enemy by racial epithets, remind us that the war was about race as much as remembering the Maine. They would prefigure later examples of low morale and racial incidents during World War II and the Vietnam War.

While Berners documentary account and narration of the Spanish-American War era justifiably does not proceed beyond its settlement, he does quote Carl Sandburgs judgment that it was a small war edging toward immense consequences. Perhaps not even Sandburg would be prescient enough to realize the extent to which the experience and consequences of our Splendid Little War would reverberate throughout the century to come.

Our behavior toward people that we annexed during and after the war brings to mind a comment made by Anthony Everitt in The Rise of Rome (2012) that imperialists may comfort themselves with their benevolence, but it is in their nature to intrude, to decide from a distance, to believe that the consent of provincials to foreign rule is freely given and not simply a rational response to the use of force (309). Convinced that non-Caucasians were incapable of ordered government and economic progress without instruction and supervision and concerned about the possible consequences to our global strategic needs, we annexed Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines as territories (never calling them colonies) while Progressives ignored their indigenous movements for self-government. It is true that we did not follow European or Japanese example and construct a nakedly exploitative American Empire. Instead, we prepared our territorial peoples for civilization, but in our own good time. Between 1907 and 1916, the Filipinos were granted a civilian government and educational system (in English), given special status as nationals, and sincerely promised independence (delayed by circumstances until 1946). Similarly, Puerto Ricans were granted American citizenship by 1917, achieving the (clumsy) status of a Free Associated State after World War II, with a fully elective government.

Next page

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.