The United States in Puerto Rico 1898-1900

Copyright 1966 by

The University of North Carolina Press

Manufactured in the United States of America

Library of Congress Card Catalogue Number 6619279

Printed by the Seeman Printery, Durham, North Carolina

To my father and mother with deep gratitude

and

To many Puerto Ricans whose friendship I value highly

Acknowledgments

To acknowledge is to recognize, and I do admit indebtedness to many persons in the labors of gathering materials and of evaluation in the writing of this book. So many have helped that I shall omit all names, lest someone be forgotten. But let it be said that I am most indebted to the gracious personnel of the National Archives in Washington, D.C., to members of the faculty and staff of the University of Puerto Rico, Georgetown University, and Fordham University.

Having set as a principle a nonrecognition of names, let me violate it with one exception. I recall with gratitude many hours of learning from the now deceased Monsignor Mariano Vasallo, who for many years was Chancellor of the Diocese of San Juan. His knowledge of the history of Puerto Rico at the turn of the century and his wisdom of insight helped me to see more clearly.

Contents

PART I

PUERTO RICO WITHIN THE SPANISH COLONIAL EMPIRE DURING THE NINETEENTH CENTURY

PART II

PUERTO RICOS EARLY YEARS WITHIN THE UNITED STATES TERRITORIAL SYSTEM

Introduction

The years 1898 to 1900 represent a change from the autonomous constitution that Spain had granted Puerto Rico in 1897 to the civil government that the Congress of the United States legislated in 1900. This period is marked by essential changes in political, social, religious, and educational life. In order to understand the cultural status and political reaction of Puerto Ricans upon entering the territorial system of the United States, it is necessary to present a survey of the islanders striving for political home-rule during the nineteenth century. This will explain in good part the tensions that characterized the relations of the United States and Puerto Rico from the first days of change of sovereignty in 1898. It is highly significant that at the moment of occupation by the United States, the island was possessed of a significant degree of administrative autonomy and that this autonomy represented long years of labor in the nineteenth century.

The coming of the United States to Puerto Rico was first regarded by the Puerto Ricans as an opportunity to participate in Anglo-Saxon political life and legal procedures. But the days of enchantment were shortened, for the military governments were exacting and did not extend the full political and legal rights of continental United States to the island. Even when the first civil government was instituted under the Foraker Act of 1900, the hallmark of colonial dependence was most apparent, and the Puerto Ricans expressed their disappointment.

In attempting to understand this political disillusion, one must know something of the many cultural strands that blended into a unity and comprised the Puerto Rican tradition. The strongest fiber in this tradition was the philosophy of the individual and of his rights in society. This heritage was deeply rooted in a past inherited from Spain; moreover, it had felt the influence of the Americas, where independence from Europe had become a reality and where new ideas were being molded. Puerto Ricans had long desired self-determination and representative government. Alongside this political goal was a religious status: the Puerto Ricans traditional adherence to Catholicism. In this he retained much of the cultural shell of revealed religion, along with the substance of its code of moral living, but lost contact with a great part of the philosophical and theological foundations of the Catholic faith.

More harmful to Christian life than such nominal Catholicism was the practice of royal patronage which placed control of ecclesiastical affairs in the hands of the crown. By 1898 there had been four centuries in which clerical appointments, financial control, and supervision of church operations had pertained to the Spanish throne. This identity of church and state was a constant source of conflict. The church lost its vigorous independence. The new thought of the eighteenth- and nineteenth-century liberals was passionately opposed to church influence and voiced a strong anticlerical propaganda. Its expression was strongly reflected in educational circles. At the turning into the twentieth century, the church also encountered an opposition from the Protestant evangel that accompanied the military forces of the United States. The proselytizing efforts of Protestant sects, as well as their significant position in public education, soon convinced Puerto Ricans that these religious efforts were part of the new regime, and so religious tension became a part of the conflict in understanding between the United States and Puerto Rico.

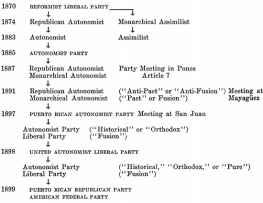

This book seeks to emphasize the tensions and essential changes that occurred during the last years of Spains hegemony and the first years of United States sovereignty. The first two chapters describe the conflict in ideas that the nineteenth century brought to Puerto Rico, as well as the growth of their political institutions. It is a sketch of the evolution from colonial servitude to assimilation into Spanish citizenship and the peninsular party system and finally to a type of administrative autonomy. These chapters are extended in order to inform readers from the continental United States of the political evolution in Puerto Rico. Succeeding chapters review the operation of the United States military governments in Puerto Rico from 1898 to 1900 and analyze the pressures that affected Congress in its drafting of a civil government for Puerto Rico. Thereupon we study the beginnings of civil government under the Foraker Act.

It was originally proposed that two final chapters be written on church-state relations and educational problems in nineteenth-century Puerto Rico. Wiser counsel and reflection have urged the following of a chronological order and the incorporation of such special topics into the time-order telling of Puerto Ricos story of change in sovereignty from Spain to the United States. A last chapter presents the religious and educational conflicts in the first years of United States occupation of Puerto Rico.

This book is directed primarily to those in the continental United States who are uninformed on the history of Puerto Rico, a free associated state (commonwealth) of the federal union. Though this writing is entitled The United States in Puerto Rico, 18981900, the author has sketched the nineteenth-century backgrounds in Puerto Rican history. It is hoped that this will serve as an insight into the ideas and institutions that came into conflict upon the entrance of the United States into Puerto Rican life. It is by no means an exhaustive treatment of the period but only aspires to open up an area of history for further investigation.

PART ONE

Puerto Rico within the Spanish Colonial Empire during the Nineteenth Century

I

Evolution of Ideas and Institutions in Puerto Rico during the Nineteenth Century

The cultural and spiritual contribution of Spains colonizing in the New World has been much debated. Some writers have exaggerated the greatness of her cultural and civilizing influence; others have over-stressed the severity of her colonial policy. Whatever may be the truth, it cannot be denied that Spain left an indelible impression on the cultural forms of Hispanic America. Any attempt to erase what is an essential part of the thought and institutions of the Hispanic American world is futile. Nevertheless, Spain failed to produce a dynamic evolution of her ideological and cultural influence, and this ultimately led to the breaking of the political bonds. This failure can be attributed to a blindness in seeing that the colonials were sons of Spain with the same inherited individualism and love of self-government that characterized the peninsular Spaniards. Her policy of sending