Pagebreaks of the print version

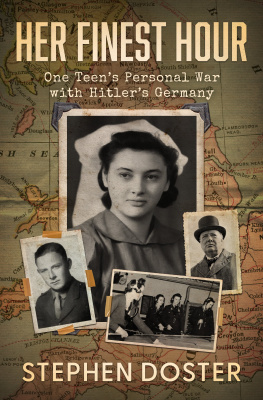

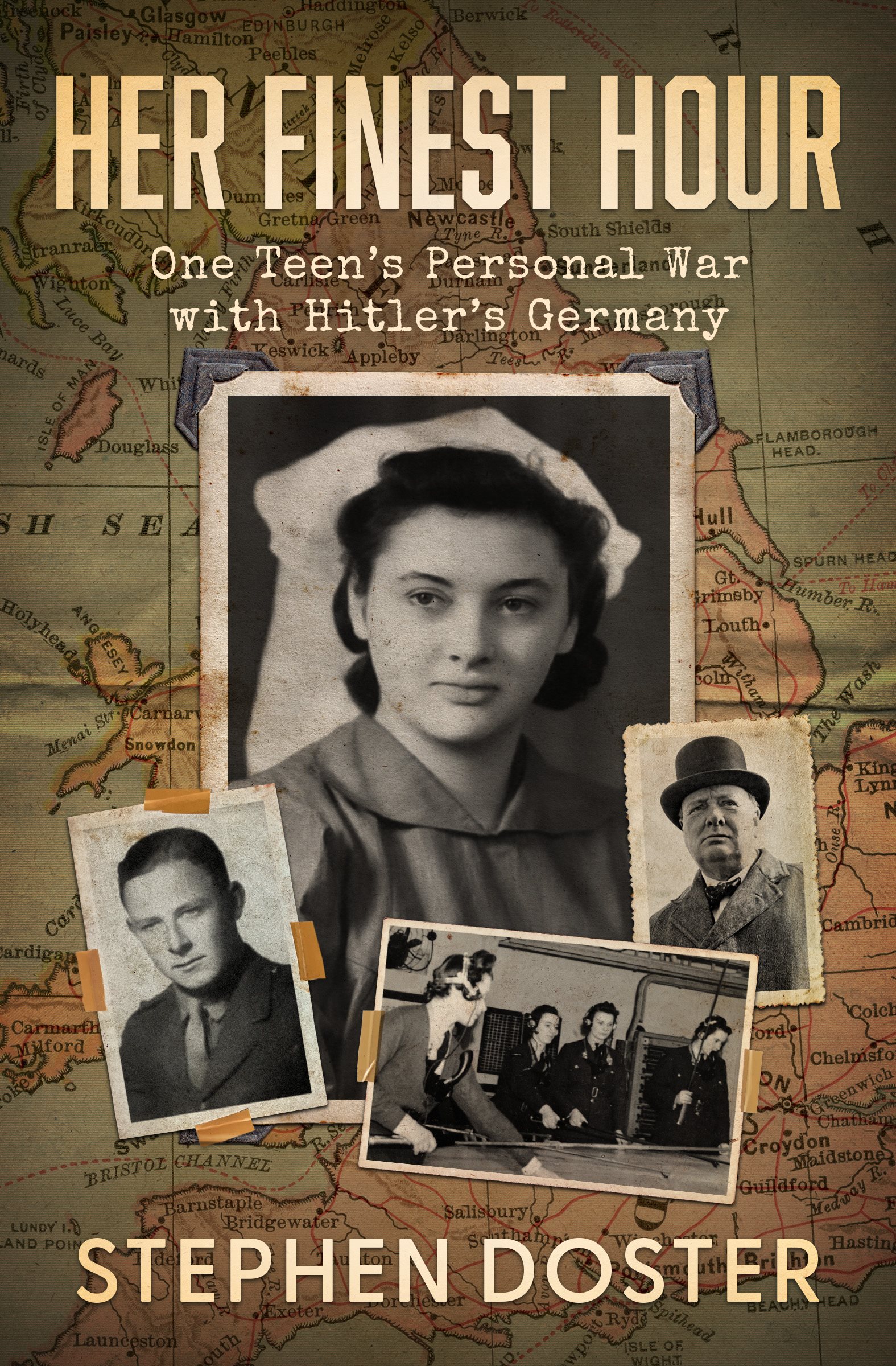

Her Finest Hour

One Teens Personal War with Hitlers Germany

Stephen Doster

The Battle of France is over. I expect that the Battle of Britain is about to begin. Upon this battle depends the survival of Christian civilization. Upon it depends our own British life, and the long continuity of our institutions and our Empire. The whole fury and might of the enemy must very soon be turned on us. Hitler knows that he will have to break us in this island or lose the war. If we can stand up to him, all Europe may be freed and the life of the world may move forward into broad, sunlit uplands. But if we fail, then the whole world, including the United States, including all that we have known and cared for, will sink into the abyss of a new dark age made more sinister, and perhaps more protracted, by the lights of perverted science. Let us therefore brace ourselves to our duties, and so bear ourselves, that if the British Empire and its Commonwealth last for a thousand years, men will still say, This was their finest hour .

Winston Churchills speech to the House of Commons of the Parliament of the United Kingdom on 18 June 1940

Introduction

General von Studnitz, who had served as German military attach in Poland, said he appreciated it was the duty of the [U. S. military navel] attachs to gather intelligence for their government and he was quite willing to inform us fully and frankly. Von Studnitz gave the attachs a clear and concise summary of the military campaign to date and predicted that mopping up operations in France would not require more than another ten days, after which preparations would begin for crossing the channel to England. Von Studnitz believed the British, without a single army division intact and most of their heavy artillery abandoned at Dunkirk, would not resist. Hillenkoettner asked how the Germans would cross the Channel, but von Studnitz brushed aside this question with the comment that all plans were made. The war, he added, would be over by the end of July, in six weeks.

Charles Glass, Americans in Paris: Life & Death Under Nazi Occupation , London, Penguin Books, 2009, pp. 19-20.

What General von Studnitz and leaders of the Third Reich failed to realizebesides the fact that the English Channel precluded their effective use of blitzkrieg as a means of subduing enemy forceswas that Britain was a land of independent people, fiercely loyal to their queen, steadfast in the face of adversity, and fearless in war. These traits are exemplified by a sixteen-year-old teen named Marjorie Terry Smith who served on eight RAF stations. From her mid-teens to early-twenties, she lived in a perpetual state of war, never knowing when the next bomb might strike (her family was bombed out of three homes), losing her fiance to Rommels forces, and witnessing the horrors of warfare inflicted in friends, family, and the pilots of the RAF stations on which she served.

In recalling the past, she speaks of before the war, during the war, and after the war, three distinct timeframes that define her life. As a result, this book is divided into three main sections. Citations throughout the text correlate to notes at the back of the book, which provide more information about the people and events she references.

The hubris of General von Studnitz might be forgiven when one considers that not only was Germany engaged in a futile effort to forge an empire, they were taking on a people who had actually built an empire the sun never sets on, and, therefore, were not intimidated in the least by Herr Hitler and Co.

The British were protected by the Channel, an indomitable spirit, and Divine Providence. They also had two secret weapons. One was radar. The other was the average Brit, including one Ms. Marjorie Terry Smith.

Chapter 1

Tooting Bec, Merton Park, Terry Terry-Smith

Im Marjorie Catherine Terry Terry-Smith, although at the time I was born, I was only named Catherine Terry Smith. I was born on August the 13th, 1923 in the Florence Nightingale Nursing Home, Tooting Bec Common, South London. In the days of coach and horses when one went through a toll gate, one had to pay money and the man with the horn would blow on it to tell the toll gate keeper to come out to take their money. So it was called Tooting.

My parents were born in the Victorian era in the 19th century. My fathers family came from Lancashire where they had resided for some four or five hundred years. My mothers fathers family came from France at the time of William the Conqueror when the name was spelled T-H-I-E-R-Y and was Anglicized after they came to England to T-E-R-R-Y. My mothers mother was Irish, although she was not born in Ireland. She was born in Greenwich, England. My father was an architect and surveyor. My mother had been brought up a Roman Catholicvery devout she was. I will tell you more about that later.

We lived in Merton Park, which was a new London subdivision with houses built between the two world wars. I remember my father saying how wonderful it was to be living only 19 miles from Piccadilly Circus, and here we were surrounded by countryside and farmland. It was wonderful until the London County Council decided that the land across the other side of the High Street, which was called Morden, was going to be developed and removed some of the slums from East London out here to the countryside. Then the London underground decided to extend to our area, so where we had farmland behind us, with cows mooing vaguely in the distance, we suddenly had trundling out from the bowels of the earth; the underground trains coming to the terminal. For some reason they called the terminal Morden, although it came out in Merton Park.

So, we were soon surrounded by part of London and the noise of the underground. Merton Park was wrapped around an old village or little town called Merton. I went to Merton Park School, a little parochial school across the street from St. Marys, a Saxon church where I was confirmed. To get to the school you went through an enclave of very old houses, and suddenly we were in another century. Back in the day, Lord Nelson and Lady Hamilton worshipped there because they lived in Merton. His hatchments were on the wall in his little pew. There was an unusual feature, what they called a spy hole, built into the church wall so people who were thought to be unclean or had a disease could take part in the service. They would be outside the church looking in and could see through to the altar area. I took confirmation classes in the rectory, which was a sort of a Georgian house or early Victorian next to the church. I would walk through a Sexton archway and have confirmation classes in the vicars drawing room. After the war I worked at the BBC and was told by Heather

Evans, who was also from Merton Park, that part of the churchs roof had been damaged by a bomb.

The Reverend Dunk had been a wartime, World War I pilot. There was a propeller right over his mantel piece, the fire pit. I would go around daydreaming about Reverend Dunk. We nicknamed him Drunk, which was very unkind because he was a charming man. I could see him fighting the Red Baron in dramatic aerial fights. The confirmation class would be over and I hadnt heard a word they said. Somehow I managed to be confirmed by the Bishop of Guilford.