Compilation copyright 2019 by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company.

Cry of the Kalahari copyright 1984 by Mark Owens and Delia Owens

The Eye of the Elephant copyright 1992 by Delia Owens and Mark Owens

Secrets of the Savanna copyright 2006 by Mark Owens and Delia Owens

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to or to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 3 Park Avenue, 19th Floor, New York, New York 10016.

hmhbooks.com

Cover design by David Vargas

eISBN 978-0-358-31516-2

v3.1020

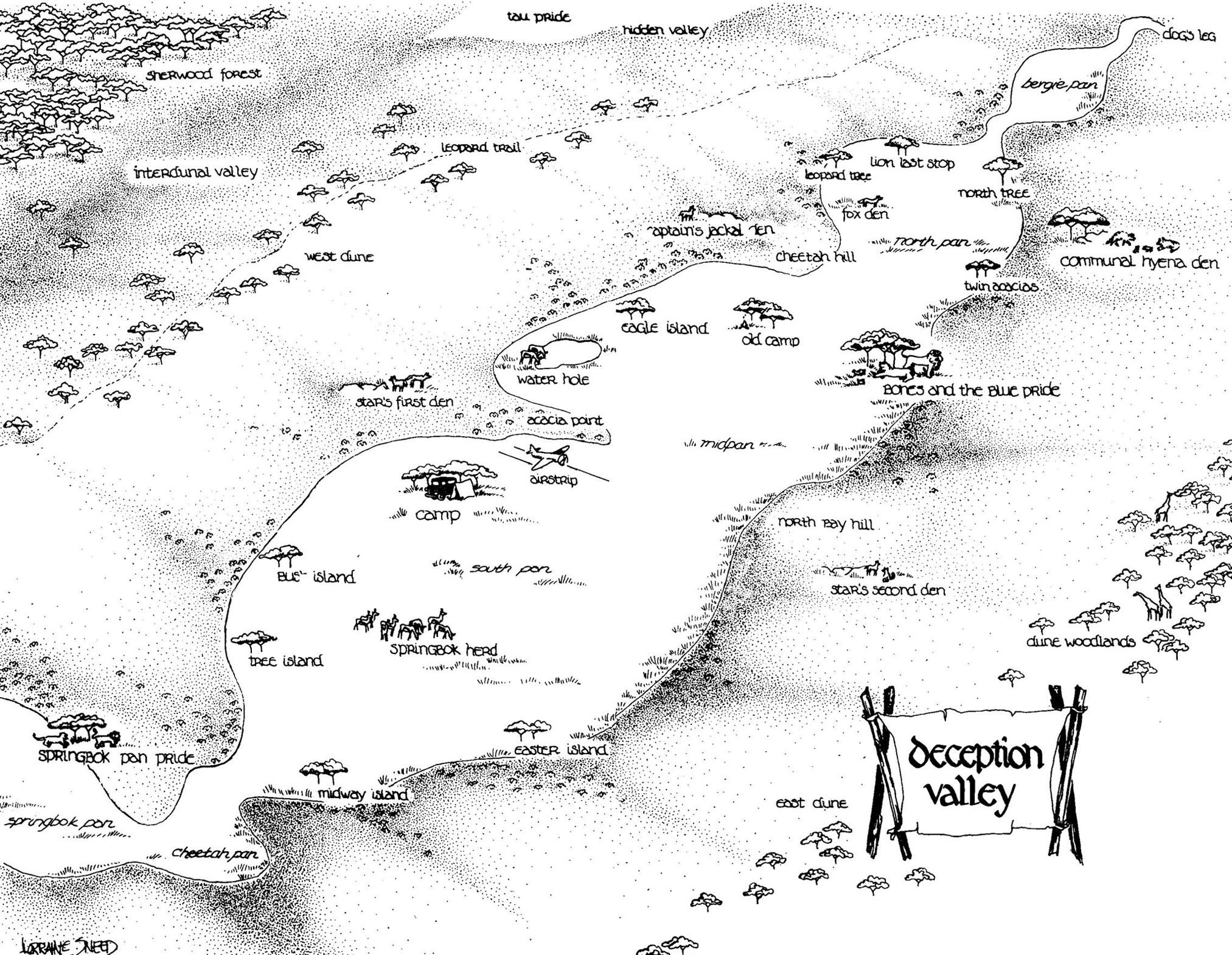

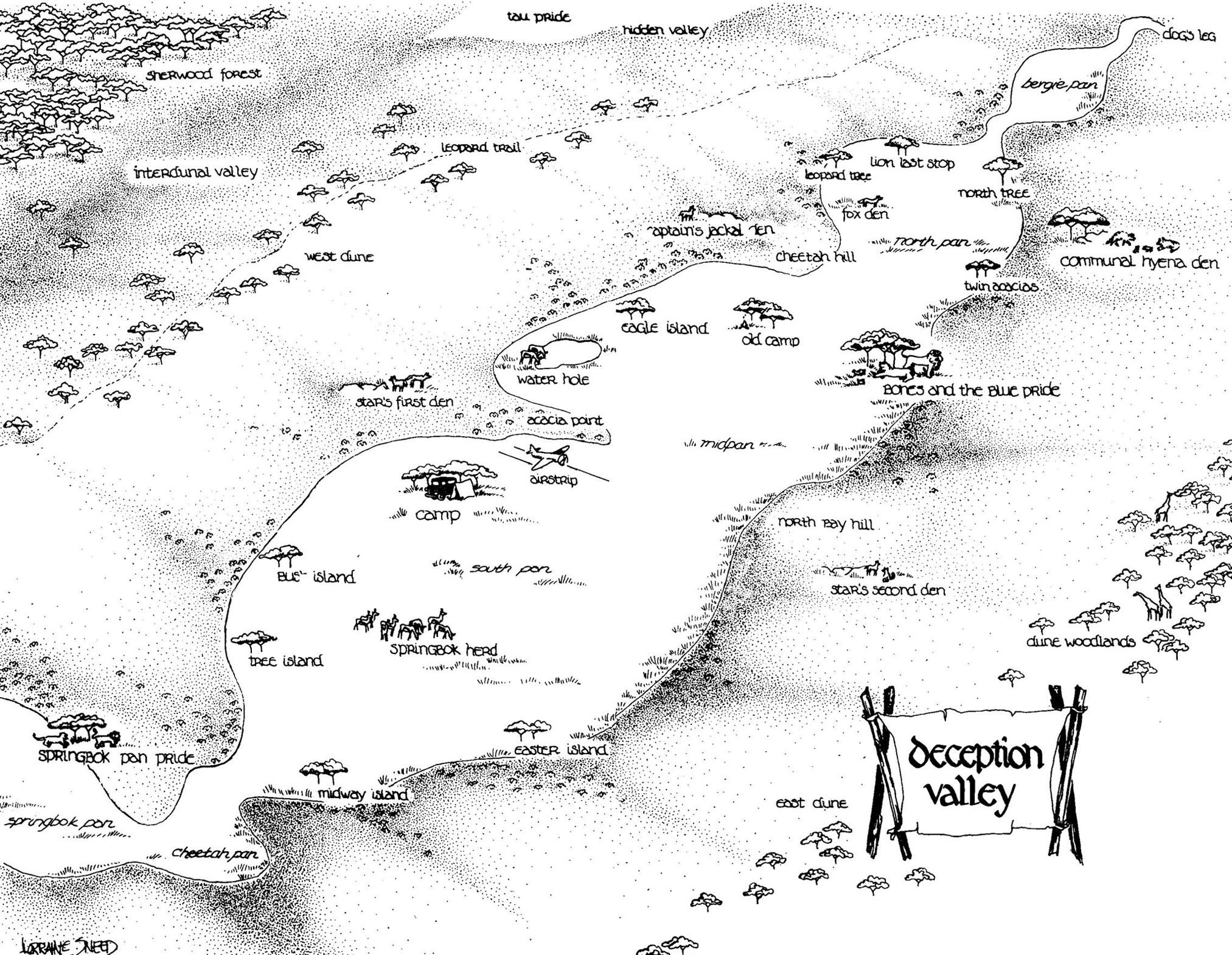

Maps on drawn by Lorraine Sneed.

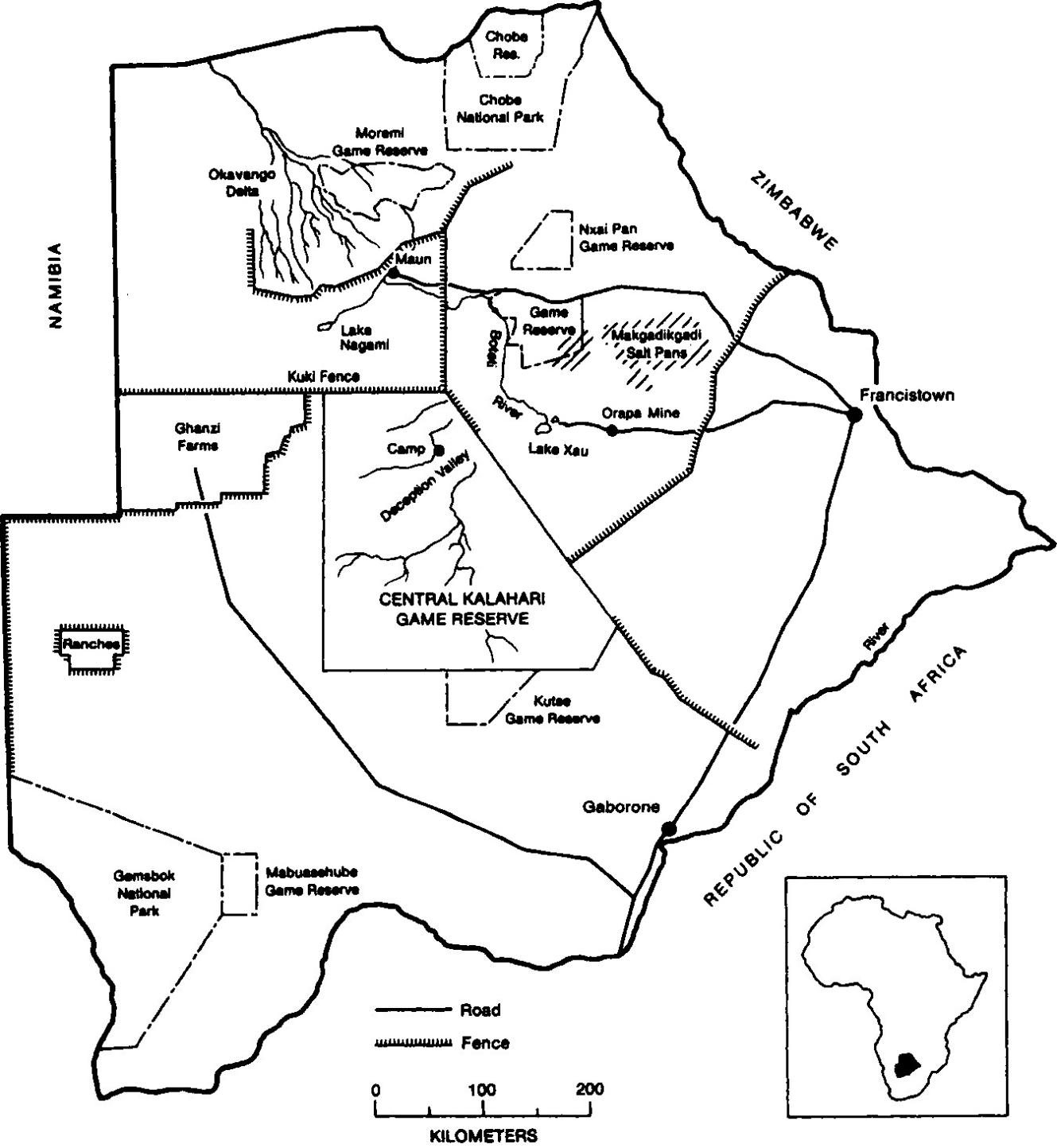

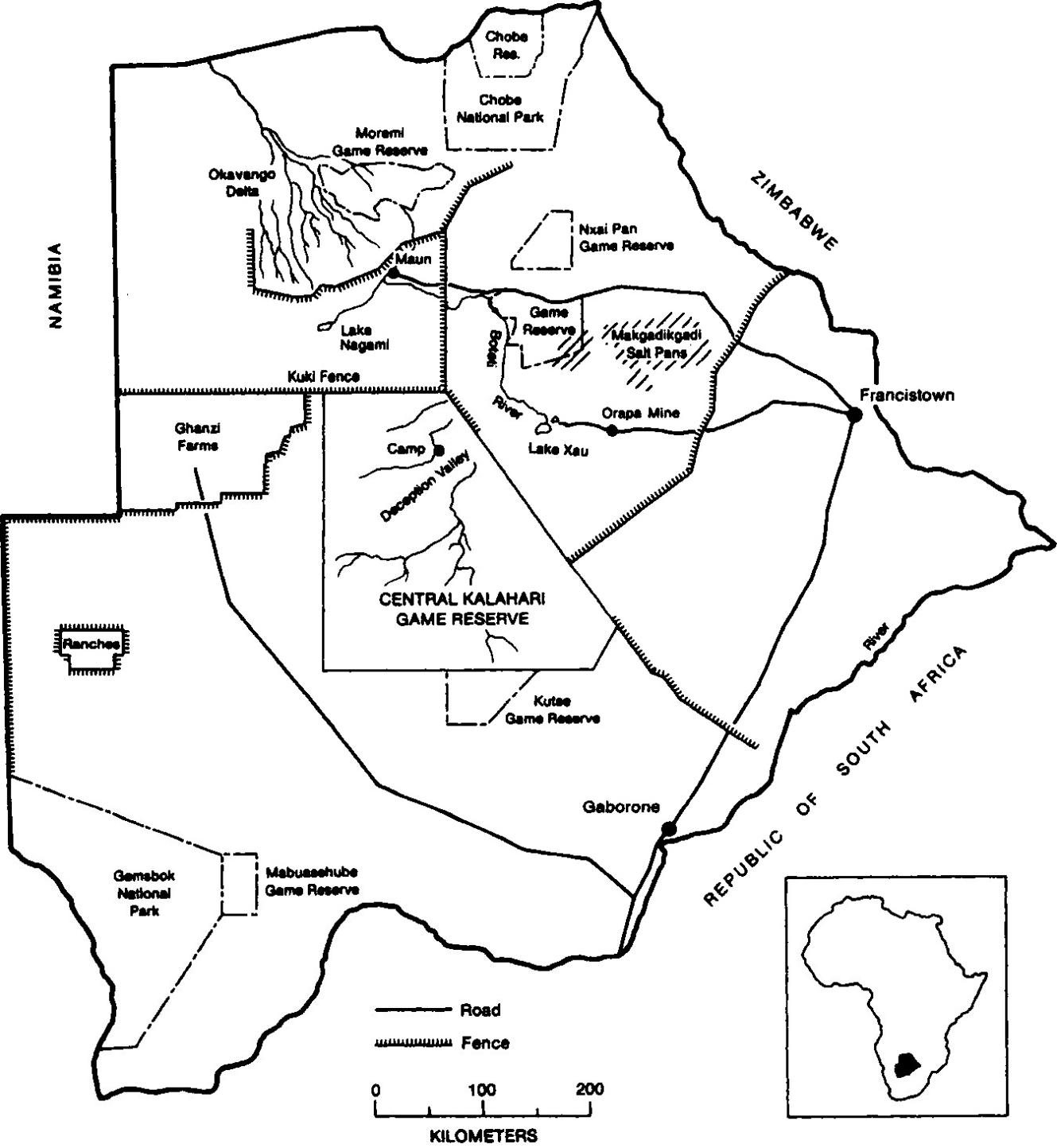

Maps on prepared by Larry A. Peters

Copyright 1984 by Mark and Delia Owens

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to or to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 3 Park Avenue, 19th Floor, New York, New York 10016.

hmhbooks.com

The Library of Congress has cataloged the print edition as follows:

Owens, Mark.

Cry of the Kalahari.

Includes bibliographical references.

1. ZoologyKalahari Desert. 2. ZoologyBotswana. 3. Kalahari Desert. I. Owens, Delia. II. Title.

QL337.K3095 1984 591.9681'1 84-10771

ISBN 978-0-395-32214-7 hardcover

ISBN 978-0-395-64780-6 paperback

ISBN -10: 0-395-64780-0 paperback

e ISBN 978-0-544-34164-7

We dedicate this book to

Dr. Richard Faust

and to

Ingrid Koberstein

of the Frankfurt Zoological Society

for all they have done for the animals

of this earth.

And to Christopher, who could not be with us.

The Republic of Botswana

Prologue

Mark

M Y LEFT SHOULDER and hip ached from the hard ground. I rolled to my right side, squirming around on grass clumps and pebbles, but could not get comfortable. Huddled deep inside my sleeping bag against the chill of dawn, I tried to catch a few more minutes of sleep.

We had driven north along the valley the evening before, trying to home on the roars of a lion pride. But by three oclock in the morning they had stopped calling and presumably had made a kill. Without their voices to guide us, we hadnt been able to find them and had gone to sleep on the ground next to a hedge of bush in a small grassy clearing. Now, like two large army worms, our nylon sleeping bags glistened with dew in the morning sun.

Aaoouua soft groan startled me. I slowly lifted my head and peered over my feet. My breath caught. It was a very big lionessmore than 300 poundsbut from ground level she looked even larger. She was moving toward us from about five yards away, her head swinging from side to side and the black tuft on her tail twitching deliberately. I clenched a tuft of grass, held on tight, and froze. The lioness came closer, her broad paws lifting and falling in perfect rhythm, jewels of moisture clinging to her coarse whiskers, her deep-amber eyes looking straight at me. I wanted to wake up Delia, but I was afraid to move.

When she reached the foot of our sleeping bags, the lioness turned slightly. Delia! S-s-s-h-h-hwake up! The lions are here!

Delias head came up slowly and her eyes grew wide. The long body of the cat, more than nine feet of her from nose to tuft, padded past our feet to a bush ten feet away. Then Delia gripped my arm and quietly pointed to our right. Turning my head just slightly, I saw another lioness four yards away, on the other side of the bush next to us... then another... and another. The entire Blue Pride, nine in all, surrounded us, nearly all of them asleep. We were quite literally in bed with a pride of wild Kalahari lions.

Like an overgrown house cat, Blue was on her back, her eyes closed, hind legs sticking out from her furry white belly, her forepaws folded over her downy chest. Beyond her lay Bones, the big male with the shaggy black mane and the puckered scar over his kneethe token of a hurried surgery on a dark night months before. Together with Chary, Sassy, Gypsy, and the others, he must have joined us sometime before dawn.

We would have many more close encounters with Kalahari lions, some not quite so amicable. But the Blue Prides having accepted us so completely that they slept next to us was one of our most rewarding moments since beginning our research in Botswanas vast Central Kalahari Desert, in the heart of southern Africa. It had not come easily.

As young, idealistic students, we had gone to Africa entirely on our own to set up a wildlife research project. After months of searching for a pristine area, we finally found our way into the Great Thirst, an immense tract of wilderness so remote that we were the only people, other than a few bands of Stone Age Bushmen, in an area larger than Ireland. Because of the heat and the lack of water and materials for shelter, much of the Central Kalahari has remained unexplored and unsettled. From our camp there was no village around the corner or down the road. There was no road. We had to haul our water a hundred miles through the bushveld, and without a cabin, electricity, a radio, a television, a hospital, a grocery store, or any sign of other humans and their artifacts for months at a time, we were totally cut off from the outside world.

Most of the animals we found there had never seen humans before. They had never been shot at, chased by trucks, trapped, or snared. Because of this, we had the rare opportunity to know many of them in a way few people have ever known wild animals. On a rainy-season morning we would often wake up with 3000 antelope grazing around our tent. Lions, leopards, and brown hyenas visited our camp at night, woke us up by tugging the tent guy ropes, occasionally surprised us in the bath boma, and drank our dishwater if we forgot to pour it out. Sometimes they sat in the moonlight with us, and they even smelled our faces.

There were riskswe took them dailyand there were near disasters that we were fortunate to survive. We were confronted by terrorists, stranded without water, battered by storms, and burned by droughts. We fought veld fires miles across that swept through our campand we met an old man of the desert who helped us survive.

We had no way of knowing, from our beginnings of a thirdhand Land Rover, a campfire, and a valley called Deception, that we would learn new and exciting details about the natural history of Kalahari lions and brown hyenas: How they survive droughts with no drinking water and very little to eat, whether they migrate to avoid these hardships, and how members of these respective species cooperate to raise their young. We would document one of the largest antelope migrations on earth and discover that fences are choking the life from the Kalahari.

I dont really know when we decided to go to Africa. In a way, I guess each of us had always wanted to go. For as long as we can remember we have sought out wild places, drawn strength, peace, and solitude from them and wanted to protect them from destruction. For myself, I can still recall the sadness and bewilderment I felt as a young boy, when from the top of the windmill, I watched a line of bulldozers plough through the woods on our Ohio farm, destroying it for a superhighwayand changing my life.