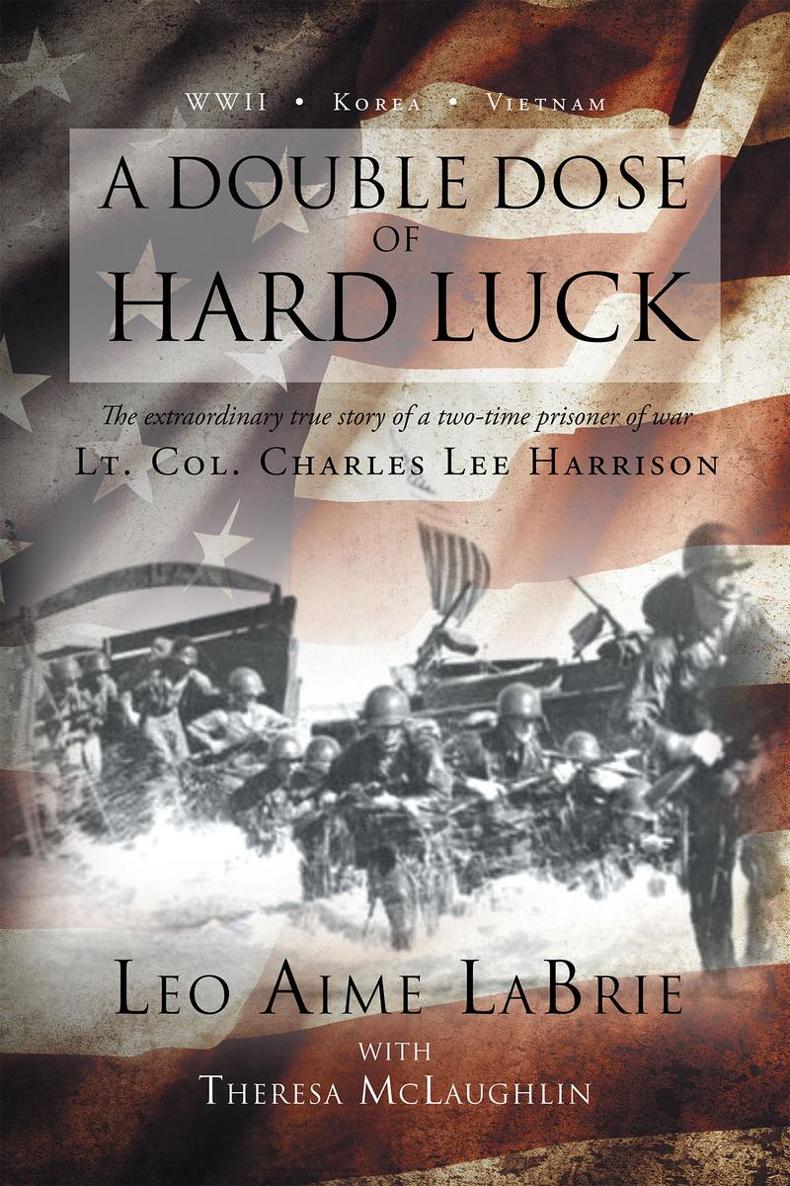

A Double Dose of Hard Luck

The Extraordinary True Story of a

Two-Time Prisoner of War

Lt. Col. Charles Lee Harrison

Leo Aime LaBrie

with

Theresa McLaughlin

Copyright 2016 Leo Aime LaBrie

All rights reserved

First Edition

PAGE PUBLISHING, INC.

New York, NY

First originally published by Page Publishing, Inc. 2016

ISBN 978-1-68409-211-6 (Paperback)

ISBN 978-1-68409-212-3 (Digital)

Printed in the United States of America

Lt. Col. Charles Lee Harrison, USMC

Foreword

I first became acquainted with Charles Harrison at the Marine Corps Recruit Depot at San Diego in July of 1958. At that time, I was a first lieutenant who was newly posted as a series officer in F Company Second Recruit Training Battalion. Charlie was then a captain and serving as one of the inspectors for the commanding general of the recruit training command. Consequently, I would frequently notice Captain Harrison observing our recruit platoons from a discreet distance while they received training from their drill instructors.

I recall that my fellow lieutenants and I grew in awe of the captain when we learned that this soft-spoken, humble, gentlemanly officer who always greeted us with a warm smile was able to claim a wartime experience so extraordinary as to be almost unbelievable. Captain Harrison, we were told, had the unfortunate distinction of being only one of two Marines to have ever suffered captivity as a prisoner of war (POW) twice in two separate conflicts. The first time was during WWII, when he became a prisoner of the Japanese army for forty-five months, following the siege of Wake Island; the second time was during the Korean War, when he, along with 150 other Marines, became surrounded and were captured by the Chinese communist forces (CCF) at the Chosin Reservoir Campaign on November 29, 1950. He remained in captivity of the CCF until he, along with seventeen fellow POWs, managed to escape from their captors six months later. Needless to say, Captain Harrison never discussed his POW experiences with the likes of us, and of course, we knew better than to raise the subject with him.

In 1994, after I had completed thirty-five years as a serving Marine officer and three additional years as the director of security for the federal aviation administration, my wife, Cathy, and I left Washington, DC, to return to the town and house in which I had been raised in Grass Valley, California. Within a year of returning to my hometown, I was pleasantly surprised to learn that Lieutenant Colonel Charles Harrison had likewise selected Grass Valley as his family home of residence after he had retired from the Marine Corps on June 30, 1969.

Although Charlie and I volunteered our time and energies to different community nonprofits, we nevertheless shared a keen interest in military history and frequently met for lunch to discuss what we were reading or to celebrate the Marine Corps birthday with our wives. Also, in June 1996, Cathy and I were privileged to be included with Charles and Marys many friends and family members when they celebrated their golden wedding anniversary. Sadly, we were also present at Marys funeral in late October of 1999 at St. Patricks Catholic Church and for her internment in the Greenwood Catholic Cemetery.

A few months after the September 11 terrorist attack, I was doing some research at the Marine Corps history division, which was then located at the Washington, DC Navy Yard. One day I happened to mention to Fred Allison, the oral historian for the division, my relationship with retired Lieutenant Colonel Charles Harrison. Fred knew of Colonel Harrison and gave me a transcript of an oral history interview that had been taken from then Staff Sergeant Harrison and several other of his fellow POWs in May of 1951. The interviews were conducted soon after the POWs had escaped their CCF captors and were returned to the custody of US forces in Korea. Fred went on to suggest that I conduct an oral tape interview of Charlies experiences as a US Marine for the history division at Headquarters Marine Corps. If Colonel Harrison would agree to the interview, Fred said he would provide me with a written interviewers guide and all the blank tapes that I would need.

When I initially raised the question of an oral interview with Charlie, he was not keen on the idea. Eventually, however, when he considered that perhaps he should do this for his children and grandchildren, he gave me the go-ahead to proceed. In order to prepare myself, I read everything I could find on the Wake Island campaign. Of particular value and the account that I found most useful was Facing Fearful Odds: The Siege of Wake Island by Gregory J. W. Urwin. Throughout my interview on the Wake Island phase, I kept this six-hundred-page volume at my side to verify facts, such as dates that Charlie could not quite recall. For example, the August date that Private Harrison, along with the initial group of First Defense Battalion Marines, arrived off Wake Island and began off-loading their equipment from the USS Regulus was easily confirmed by Dr. Urwins book.

The taping schedule that we established was two 1-hour sessions each week for five weeks. Starting with Charles growing up in Oklahoma to his retirement from the Marine Corps in 1969 resulted in a total of ten hours of oral tapes. Throughout the process, Charless memory of names and events never ceased to amaze me. For instance, he was still able to rattle off the serial number of his .03 Springfield service rifle. This was the same rifle that had been issued to him as a recruit in San Diego in 1939. My, how he must have cherished that rifle.

In describing the circumstances of losing his beloved .03 Springfield, I remember his face grew sad when he told me, It was customary during the air raids on wake for the three-inch anti-aircraft batteries to continue firing at the Japanese bombers until they released their bombs. Then our gun crew would dive for their holes or underground bunkers. Apparently, on one of the last raids, Charlies rifle was left leaning outside a bunker when his gun position received almost a direct hit from a bomb. Charlie emerged as the planes departed to find his rifle had been shattered by a large piece of shrapnel. It was as if I had lost my best friend, he lamented.

Once the interviews were finished, I shipped the tapes off to the history division at Headquarters Marine Corps. Fred Allison was pleased to have them and graciously made extra copies for Charles to pass on to members of his family, along with written transcripts.

I would like to commend Leo LaBrie and Theresa McLaughlin, for their hard work and dedication in preparing this splendid biography of my long-standing friend and fellow Marine. In my view, their account of Charles Lee Harrisons life is a fitting tribute to a remarkable human being. During his thirty-year career as a US Marine, Charles Harrison repeatedly distinguished himself as he fought and bled for his country in three major wars. Moreover, during two of those conflicts, he suffered a total of fifty-one months of extremely harsh and oftentimes brutally dehumanizing treatment while in the hands of our enemies. Yet despite his agonizing years behind barbed wire, Charles Harrison never became bitter, dejected, or spiritually broken. Instead, he continued to fight and resist against the enemy with the only weapons left to himhis faith and his courage.