Published by Brolga Publishing Pty Ltd

PO Box 12544 ABeckett St Melbourne Australia 8006

ABN 46 063 962 443

email:

web: www.brolgapublishing.com.au

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without prior permission from the publisher.

Copyright 2011 WR (Bob) Beecroft

National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry:

Beecroft, W. R.

Unbroken : the heroic true story of a group of Anzac POWs in WWII Europe

9781921596667 (pbk.)

9781922175731 (eBook)

World War, 1939-1945CampaignsAfrica North.

World War, 1939-1945Prisons and prisoners, AustralianBiography.

World War, 1939-1945Prisons and prisoners, New ZealandBiography.

World War, 1939-1945Prisoners and prisons, Italian.

Prisoners of warAustraliaBiography.

Prisoners of warNew ZealandBiography.

Prisoners of warItalyBiography.

World War, 1939-1945Personal narratives, Australian.

World War, 1939-1945Personal narratives, New Zealand.

940.547243

Cover design by David Khan

Typeset by Imogen Stubbs

FOREWORD

I have chosen to present this narrative by speaking as my father, Allan Roy Beecroft, rather than speaking of him, because he rarely spoke of himself, and now never can. I believe that many returned servicemen were reluctant to talk because there was always someone who had experienced worse conditions. But I think he would have liked to have his experiences recorded.

Like hundreds of thousands of Australians, my father came home from the war: some with visible scars and missing bits, while others, like him, showed no outward signs of their terrible experiences. In the main, these men were left to heal themselves and get on with their lives.

Most Australians are aware of the horrors suffered by Australian POWs captured by the Japanese, but few have heard about the years of captivity endured by those POWs in Europe, save those who shared the experience, and there are very few of them left to tell the tale.

Yet the torment and suffering that our prisoners suffered at the hands of the Italians, and later the Germans, was appalling. In todays world of plenitude and the relative comfort of our society, it is almost incomprehensible that these men subsisted on a diet of watery gruel and bread for almost four years, with little else than the occasional Red Cross parcel to sustain them. Added to this was the brutal repression meted out for the slightest transgression, and the endless roll calls and inspections where they were forced to assemble for hours on freezing parade grounds, scantily clad in the remnants of uniforms and cast-off enemy clothing. I was 3 years old when my father left Australia and I remember little of him before he went away. Nevertheless, on his return I recognized that he was a changed man, and would forever remain so.

For the rest of his life, he held an abiding disdain for all forms of authority and petty regulation, and jealously guarded his freedom from all forms of petty tyranny. On one occasion, he screeched to a halt when driving past a school, and jumped out to angrily confront a teacher who had been slapping a pupil about the head. He must have put the fear of god into the man, yet he had no qualms about dishing out severe thrashings to me when he thought the occasion demanded it. I quickly learned that Sergeant Majors do not necessarily make tolerant fathers.

He returned to civilian life quite seamlessly, returning to his previous position as a leading hand in the dye-house at Kelsall & Kemp, a textile factory in Invermay. He lasted perhaps a year at his old job, until an opportunity arose for him to take up a position as a motor mechanic at Heathorns, the local Morris car dealer, a vocation more suited to his ambitions. After a couple of years at this, he was offered a position as a new car salesman, and he proved to have an aptitude for this, particularly in the sales of trucks and light commercial vehicles. He remained a car salesman until his health demanded he give it up and he retired as a TPI pensioner.

My brother and I shared his love of motor sports, particularly motorcycling, and we frequently competed against each other in reliability trials, speed trials, road safety events and other clubman activities. For all the years that Longford hosted the annual road races, my father was the course announcer at Longford corner. (Conveniently located opposite the pub!)

His other great love was fishing, and this was the one aspect of his life that he and my mother shared with equal passion. He built a bondwood boat in the mid 50s, and this formed the nucleus of my parents lives until his death. We, their children, shared this camping/fishing lifestyle during much of the next decade.

My father rarely spoke to us of his wartime experiences, although we knew that he had been captured at Tobruk, and he would sometimes come out with some amusing anecdote. It was not until I read Chester Wilmots Desert Siege that I realised what a hellhole that place really was.

Once he mentioned that he had made three escape attempts from Stalag V111A, which all resulted in his inevitable recapture. As part of his punishment after the third attempt, the Germans shaved his head and made him grow a beard. I have never been able to corroborate this (and thus have not included it in this written account), although I have no doubt that there is some truth in the tale.

For many, the impression of POWs in Europe is that depicted in film and TV productions such as The Great Escape and Hogans Heroes, and such representations are insulting to the memories of those who suffered as prisoners in Europe.

I dedicate this story to the memory of those men.

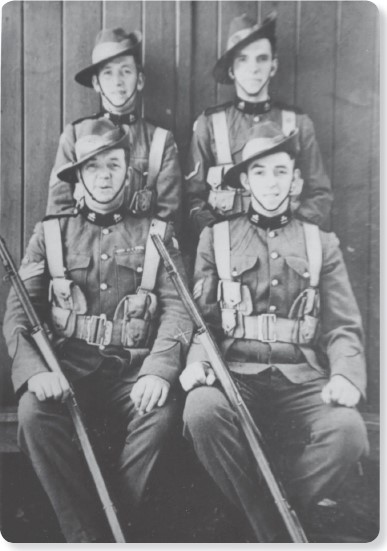

WR (Bob) Beecroft, LF with sons CW Allan Roy,

Arthur James, WR (Bill) circa 1937

PROLOGUE

T he months of July and August 1939 were filled with grief and foreboding for the family. We were all trying to come to grips with the sudden death of our father in June; he was fifty years old and died of a stroke; one day he was there, the next, gone.

On top of this, the clouds of war were once again gathering in Europe. Despite Chamberlains promise of peace in our time, Germany continued to lash out at her neighbours and to seriously build up her military might.

Dad and his brother-in-law had both enlisted at the outbreak of the Great War. In October 1914, they embarked on HMT Devana bound for Gallipoli out of Alexandria, but Dad was taken off the ship with a severe attack of gastritis and hospitalized. There were those who no doubt thought this to be a stroke of luck, but he never saw it that way. He spent most of the war in Egypt before being transferred to the Royal Flying Corps as an air mechanic, and then shipped back to Australia in June 1918 out of Suez on board SS