ESCAPE ARTIST

PETER MONTEATH is Professor of History at Flinders University in Adelaide. He is the author of POW: Australian Prisoners of War in Hitlers Reich (Macmillan 2011), and, with Valerie Munt, Red Professor: The Cold War Life of Fred Rose (Wakefield 2015).

ESCAPE ARTIST

THE INCREDIBLE SECOND WORLD WAR OF JOHNNY PECK

PETER MONTEATH

A NewSouth book

Published by

NewSouth Publishing

University of New South Wales Press Ltd

University of New South Wales

Sydney NSW 2052

AUSTRALIA

newsouthpublishing.com

Peter Monteath 2017

First published 2017

This book is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part of this book may be reproduced by any process without written permission. Inquiries should be addressed to the publisher.

Cataloguing-in-Publication data is available from the National

Library of Australia

ISBN 9781742235509 (paperback)

9781742242842 (ebook)

9781742248325 (ePDF)

Design Josephine Pajor-Markus

Cover design Luke Causby

Cover images See picture section for image credits

Maps Josephine Pajor-Markus

All reasonable efforts were taken to obtain permission to use copyright material reproduced in this book, but in some cases copyright could not be traced. The author welcomes information in this regard.

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

It is no surprise that historians before me have been drawn to the extraordinary story of Johnny Peck. Foremost among them was the late Roger Absalom, whom I met a number of times, and who had devoted painstaking research over many years to the stories of Allied POWs on the run in wartime Italy. At that time I knew nothing of the scale of Rogers interest in Johnny Peck to the extent of meeting him, interviewing him in 1986 and 1987, corresponding with him and weaving some threads of the Johnny Peck story into his wonderful book A Strange Alliance. I am grateful to Rogers dedication to his topic and to the tangible outcomes of his industry in the form of his publications and the notes contained in Pecks papers.

Western Australian historian Bill Bunbury also wrote about Peck in his book Rabbits and Spaghetti. Bill was kind enough to share with me his experience of delving into Pecks life and to help me establish contact with Pecks daughter Barbara Daniels in the UK. This book would not have been possible without Barbaras own generosity in giving me access to her collection of materials relating to her father and also providing some insightful comments on the draft manuscript. She very helpfully collected also the views of her sisters, to whom I also express my gratitude for allowing me to intrude into a part of their familys history.

For the research on Italy I am deeply indebted to Anna Banfi, who went far beyond the call of duty in tracing leads that did much to cast some light on parts of the story which for a long time seemed frustratingly obscure. The book has gained enormously from her ability to find those Italian sources and understand their importance for the bigger story.

In our resolute dedication to the cause of history, my partner Catherine Amis and I walked in the footsteps of Johnny Peck in Crete, Italy and Switzerland. I thank Catherine for her forbearance in allowing historical research to spoil a good walk (with apologies to George Bernard Shaw).

Space does not allow me to list the particular contributions of others, but let me express my heartfelt thanks in no particular order to Katrina Kittel, Elspeth Menzies, Margaret Gee, Deborah Nixon, Josephine Pajor-Markus, Tricia Dearborn, Ken Fenton, Glen Peebles, Federico Ciavattone, Philip Cooke, Richard Bosworth, Giovanni Cerutti, Claudio Perazzi, Gianmaria Ottolini, Luciano Boccalatte, Jrgen Frster, Benjamin Haas, Carlo Gentile, Kris Lipkowski, Kevin Jones, David Lockwood, Matt Fitzpatrick, Peter Stanley, Ian Jocumsen, Ross Jocumsen and Brian Dickey. Without singling out any particular individuals, I also thank the dedicated staff of the Flinders University Library, the National Archives of Australia (Canberra and Melbourne offices), the Australian War Memorial Research Centre, the Bundesarchiv-Militrarchiv Freiburg, the Imperial War Museum, the National Archives (Kew) and the Archivio Istituto Storico Resistenza Novara Piero Fornara.

Research for this project was generously supported by a research grant from the Australian Army History Unit and by Flinders University.

Finally, an unerring source of much practical information and advice was the irrepressible Bill Rudd, who has done more than anyone else to explore, record and make known the history of those he calls the ANZAC POW Free Men in Europe during World War II. Himself a former POW who had experienced life in Campo 57 and dared to climb to freedom in Switzerland, Bill has also been an inspiration to me and to many others. It is to Bill that this book is dedicated.

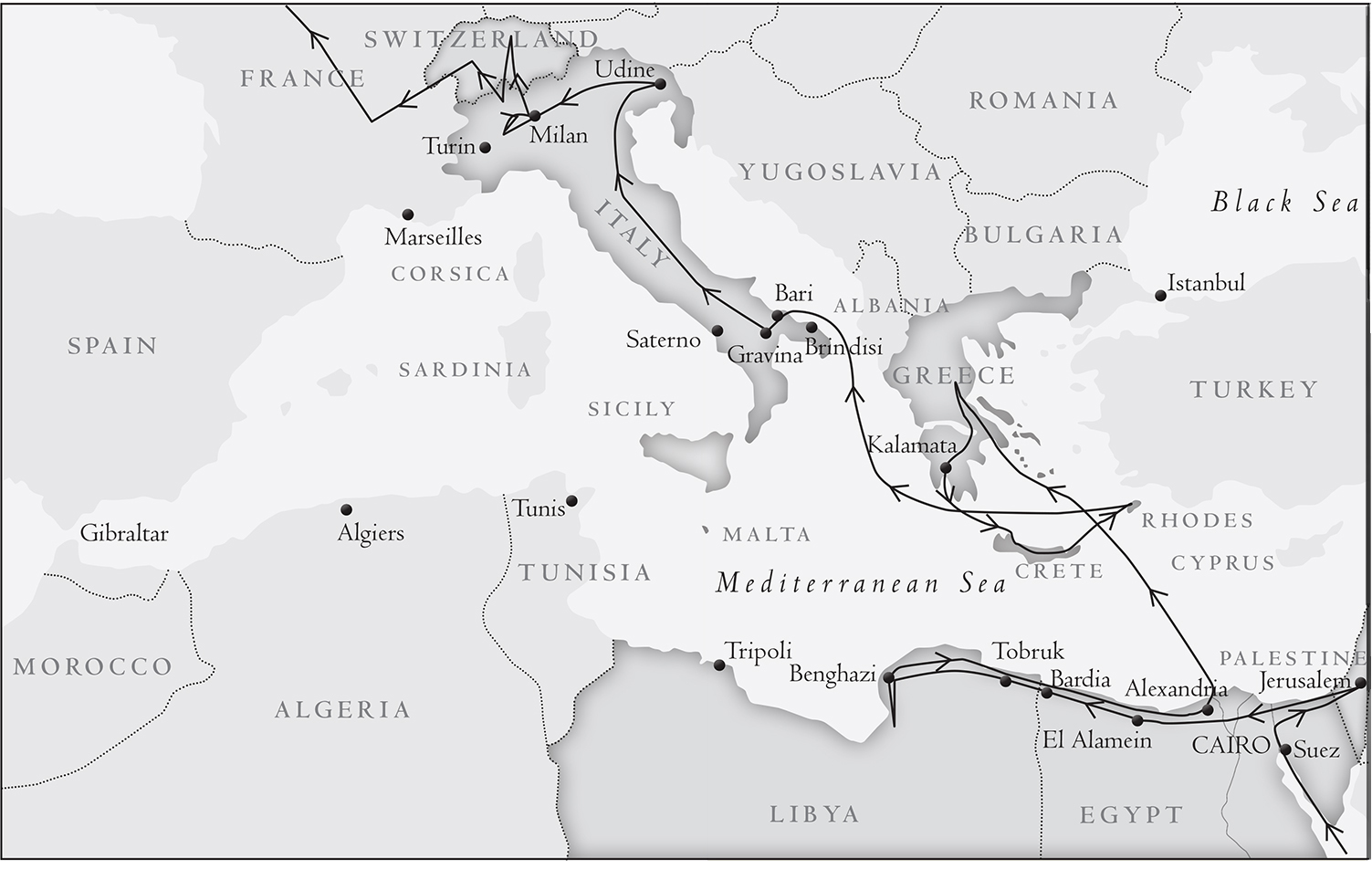

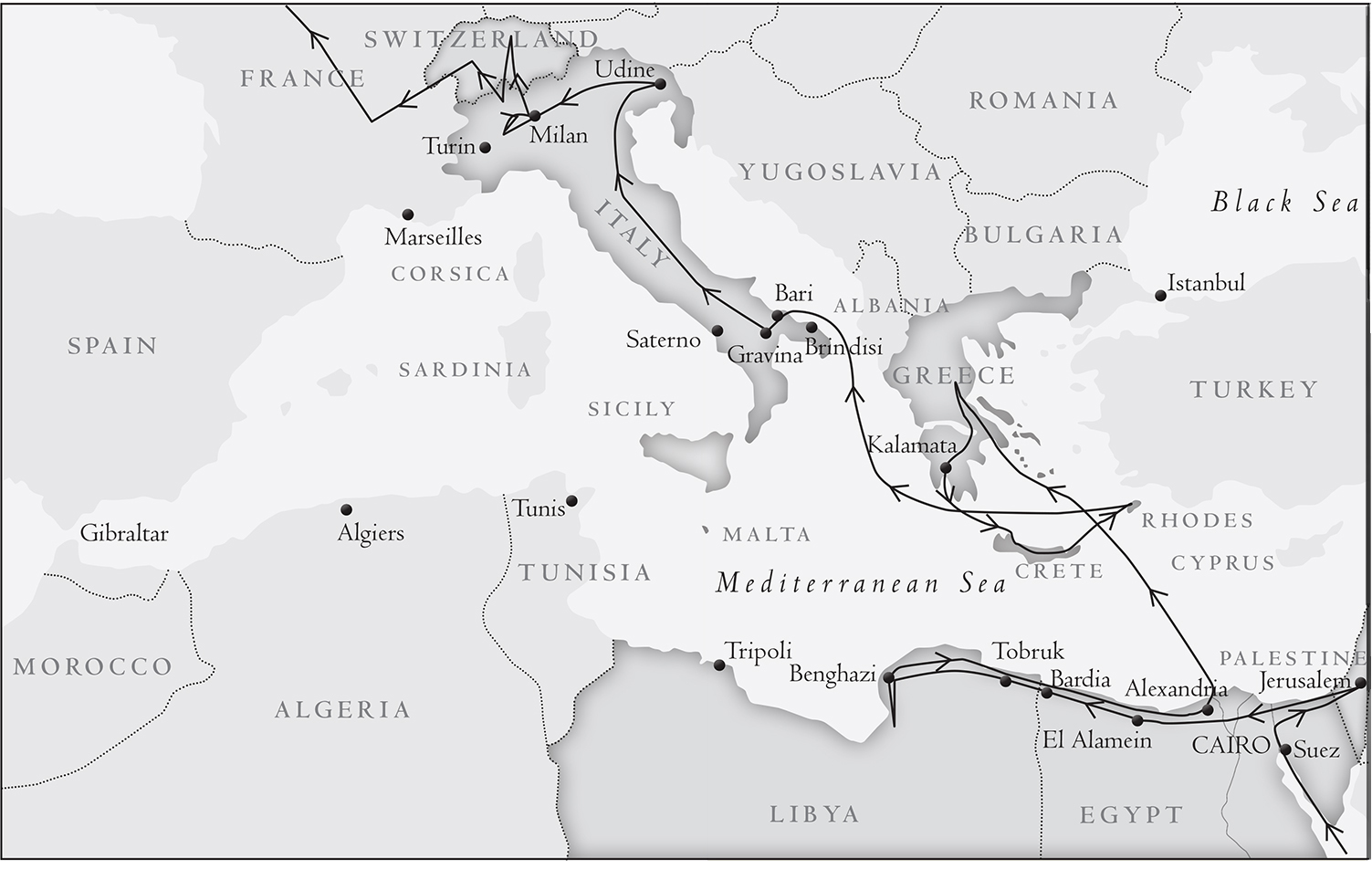

Johnny Pecks World War II odyssey February 1940 December 1944

PROLOGUE

On an unrecorded date in late September of 1943, a ragged group of Australian soldiers trudged the last metres to the ridge of the Monte Moro Pass in north-western Italy. As they paused for breath, their raised eyes drank in the sublime beauty of the wall of rock that was the Monte Rosa massif.

Behind and below them craggy goat tracks and smugglers paths wound tortuously upward from the floor of the forested Anzasca Valley, the ancient home of the Walser people. Behind them, too, were months of privation and misery in the lice-infested POW camps of Libya and Italy.

In front of them was the border that separated fascist Italy from neutral Switzerland. A soaring, gilded statue of the Virgin Mary marked the divide, her halo of snowflakes reminding all those who saw her that they traversed a rarefied world of cold and ice.

One by one the Australians commenced their descent through a jumble of rock and then down a gentle slope to a village, where their Swiss hosts would warm them, ply them with food and drink, and offer them a welcoming home for the months ahead. For these men, the war was over.

Johnny Peck observed these last moments of his charges liberation. He was their guide, but he was also one of them. He, too, had fought in the Western Desert; he knew all too well the ignominy of capture and the misery of captivity. And he, too, had seized the chance to defy his captors and leave the barbed wire behind.

But Switzerland did not beckon to the 21 year old, at least not at this time. Back down on the plains of Piedmont and around the rice fields of Vercelli, there were hundreds more POWs needing help. Their Italian guards had long since headed home, because the new masters of Italy were Hitlers soldiers. If the POWs were to avoid being snaffled by these Germans and sent north across the Alps to spend the rest of the war in a Stalag, something needed to be done, and quickly. What better man to help them than the elusive Johnny Peck, who had already embarrassed a string of captors and saw no need to stop just yet.

More than that, there were still battles to be fought and a war to be won. After the ignominies of Libya, Greece and Crete, there was at last a chance to turn the tables on Hitlers armies. Stretched to its limits, Hitlers Reich was tottering, and Johnny Peck instinctively knew it.

Next page