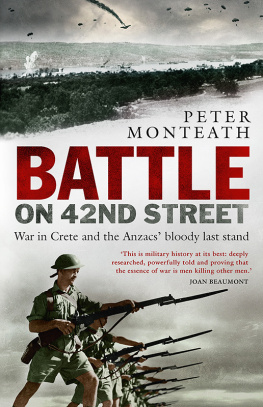

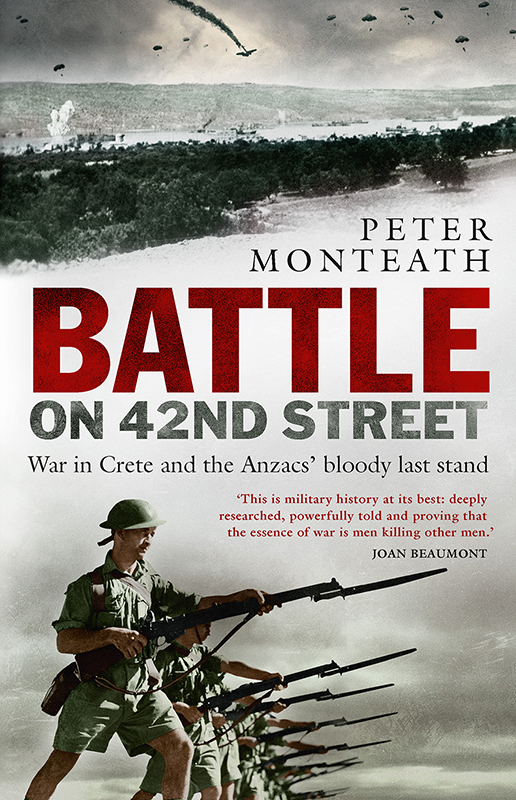

BATTLE

ON 42ND STREET

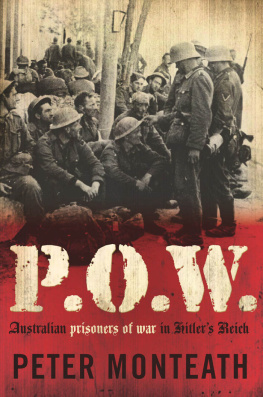

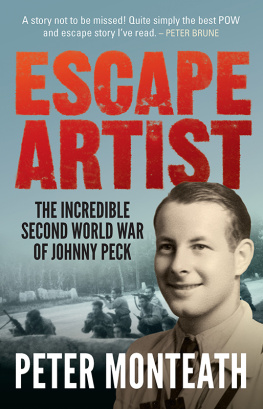

PETER MONTEATH is Professor of History at Flinders University in Adelaide. His books include POW: Australian Prisoners of War in Hitlers Reich and Escape Artist: The Incredible Second World War of Johnny Peck. His research for this book took him to archives in Australia, New Zealand and Germany and to 42nd Street.

Ka tuwhera te twaha o te riri,

kore e titiro ki te ao mrama

When the gates of war have been flung open, man no longer takes notice of light and reason

(Mori proverb)

BATTLE

ON 42ND STREET

War in Crete and the Anzacs bloody last stand

PETER MONTEATH

A NewSouth book

Published by

NewSouth Publishing

University of New South Wales Press Ltd

University of New South Wales

Sydney NSW 2052

AUSTRALIA

newsouthpublishing.com

Peter Monteath 2019

First published 2019

This book is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part of this book may be reproduced by any process without written permission. Inquiries should be addressed to the publisher.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of Australia

ISBN: 9781742236032 (paperback)

9781742244686 (ebook)

9781742249186 (ePDF)

Design Josephine Pajor-Markus

Cover design Luke Causby, Blue Cork

Cover images (front) German parachute troops over Suda Bay during the invasion, Crete, 20 May 1941 (Australian War Memorial 128433); Men of the Australian 2/7th Battalion training with fixed bayonets, Biet Jerjia, Palestine, May 1940 (Australian War Memorial 001947, negative by Damien Parer); (back) German graves, not long after the battle on 42nd Street (Dimitris Skartsilakis)

Maps Josephine Pajor-Markus

All reasonable efforts were taken to obtain permission to use copyright material reproduced in this book, but in some cases copyright could not be traced. The author welcomes information in this regard.

Contents

Prologue

War is the realm of physical exertion and suffering.

These will destroy us unless we can make ourselves indifferent to them, and for this birth or training must provide us with a certain strength of body and soul.

Carl von Clausewitz

L ate in 1940, a company of British engineers, the 42nd Field Company, set up camp in olive groves a short distance from Suda Bay on the island of Crete. Though it was November and the season had turned, to these British soldiers Crete seemed a warm and welcoming haven, untouched by the wars being waged to their south in Africa and to their north in continental Europe. While there was talk that Mussolini might disturb the islands peace, no-one believed it, or preferred not to. That the engineers thoughts lay elsewhere was signalled by their choice of name for the dusty, sunken road running through their bivouac, from the foothills toward the western shore of Suda Bay, with its iridescent waters and gently lapping waves. In ironic self-reference, and with memories of the eponymous 1933 Hollywood film swirling through the minds of some, that dirt road became 42nd Street. And while the 42nd Field Company moved on, the name stuck.

Half a year later, in May 1941, war did come to Crete after all. The Battle for Crete was at once the most modern and the most ancient of wars. In the space of just a few hours on 20 May 1941, any hopes that Crete might be spared the high-tech savagery that had laid waste the Greek mainland and large swathes of Europe further to the north were abandoned. What followed in Crete were twelve days of unremitting bloodshed in a struggle which posed that most crucial of questions to soldiers on both sides. In the heat of battle, did they possess the desire and the ability to do what they were required to do to kill?

In the twentieth century, the soldiers main task had been rendered much easier than in any other age by the advance of military technology. Death could be delivered from great distances, the awful consequences hidden from sight and from earshot. Killers and killed alike were not just unacquainted with each other but mercifully unable to draw any clear line of blame or responsibility. In the Great War it was artillery above all that caused carnage, mangling bodies and destroying lives on an unimagined scale. Shrapnel could sever limbs, while machine-guns, grenades, mortars and landmines, too, could make a mess of mens bodies and minds. A generation later, the capacity to kill large numbers from great distance had grown further. Artillery and machine-guns had been given wings. Not only soldiers but civilians, too, were subjected to anonymous, indiscriminate killing orchestrated from the skies.

All of this was well known to the weary Australians and New Zealanders who in the night of 26 to 27 May snatched precious moments of rest among the olive trees along 42nd Street. For a full week they had been relentlessly hammered from the skies by the Luftwaffe and pursued across Crete by some of the most accom-plished and best equipped forces Hitler could muster. Before that, through most of the month of April, the Anzacs had been chased by the Wehrmacht down the length of mainland Greece, from the icy heights of Vevi in the far north to the southernmost ports and beaches.

All that, however, was about to change. On the morning of 27 May, in the sun-drenched groves that had afforded the Anzacs precious respite through the night, neither the Luftwaffes mastery of the air nor German firepower on the ground would count for much. As a unit of German mountain troops, newly arrived on the island, wended its way through the morning shadows toward 42nd Street, the Anzacs stirred from their slumbers. With lines of sight blocked by trees, on this occasion the battle would be an intimate affair.

Just how a soldier will fare when confronted with the kind of test that was about to be set both sides at 42nd Street is a mystery which occupies every army. Theory alone could not reveal whether men possessed the certain strength of body and soul demanded by the great Prussian general and military theorist Carl von Clausewitz. Soldiers could be trained to a peak of physical fitness, instructed in the use of their weapons and drilled to respond with unthinking obedience. Ultimately, however, it was only in combat that the answers to the most vital of questions would finally be known. Facing their enemies rather than their drill sergeants, would soldiers be able to overcome their fear of dying? More than that, would they be able to overcome their fear of killing? Would they find themselves merely there on the field of battle, following the most basic of instincts of self-preservation? Or would they be transported into the kind of state of mind that would lead them not just to kill but to enter, at least for a short, mad time, a state of bloodlust? In the shady groves along 42nd Street, both sides would have their answer. Bayonets were fixed.

Next page