Contents

Table of Contents

Guide

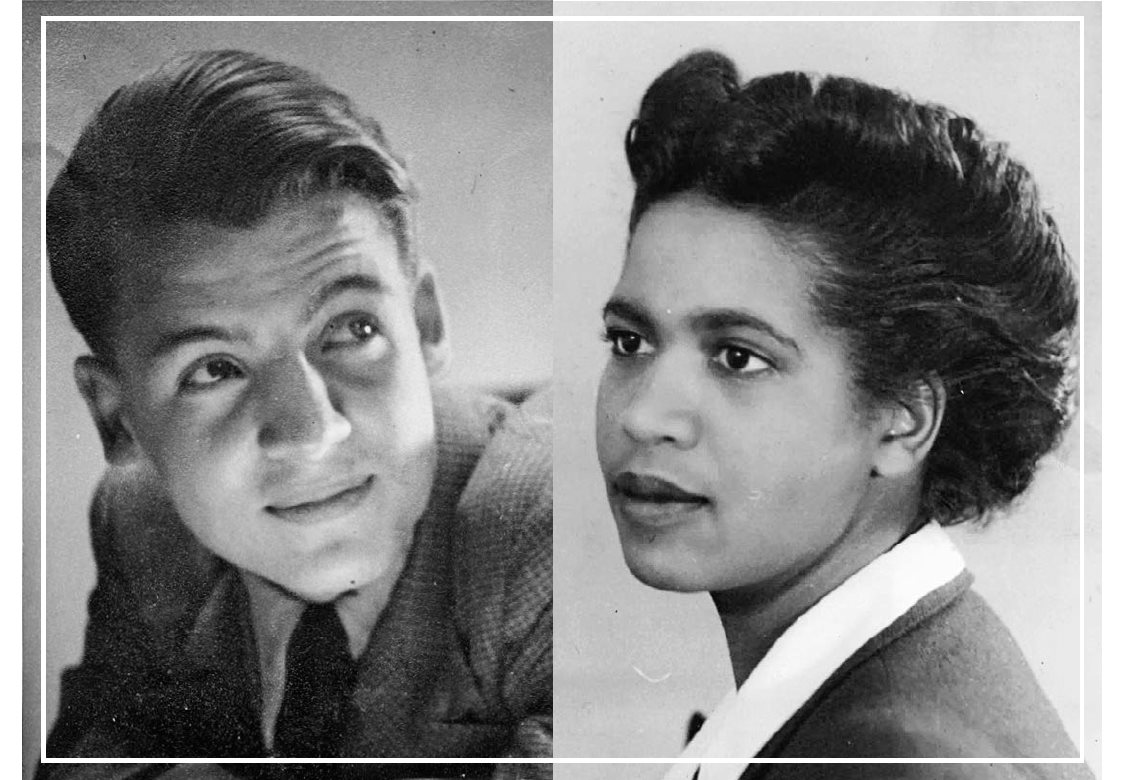

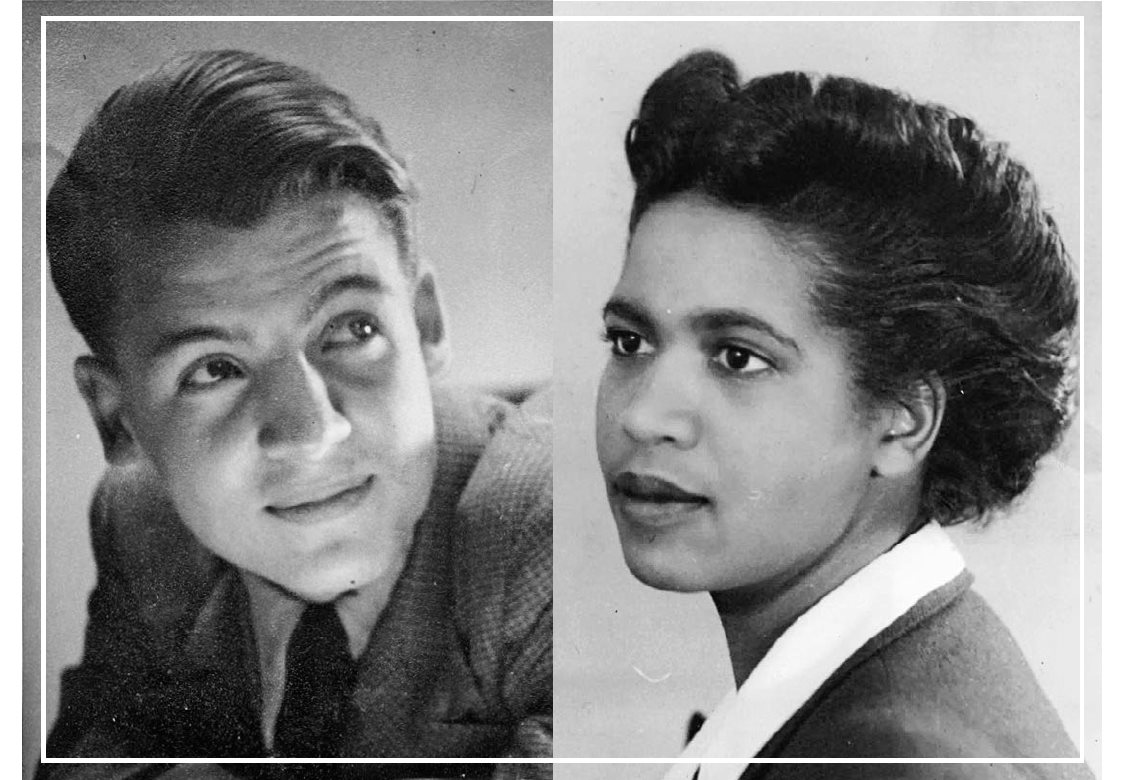

Jacket and interior photographs courtesy of Chris Albert

2018 by Alexis Clark

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced, in any form, without written permission from the publisher.

Requests for permission to reproduce selections from this book should be mailed to: Permissions Department,

The New Press, 120 Wall Street, 31st floor, New York, NY 10005.

Published in the United States by The New Press, New York, 2018

Distributed by Two Rivers Distribution

ISBN 978-1-62097-187-1 (e-book)

CIP data is available

The New Press publishes books that promote and enrich public discussion and understanding of the issues vital to our democracy and to a more equitable world. These books are made possible by the enthusiasm of our readers; the support of a committed group of donors, large and small; the collaboration of our many partners in the independent media and the not-for-profit sector; booksellers, who often hand-sell New Press books; librarians; and above all by our authors.

www.thenewpress.com

Book design by Lovedog Studio

Composition by dix!

This book was set in Bembo

2 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 1

To my parents,

Ben and Jennifer Clark

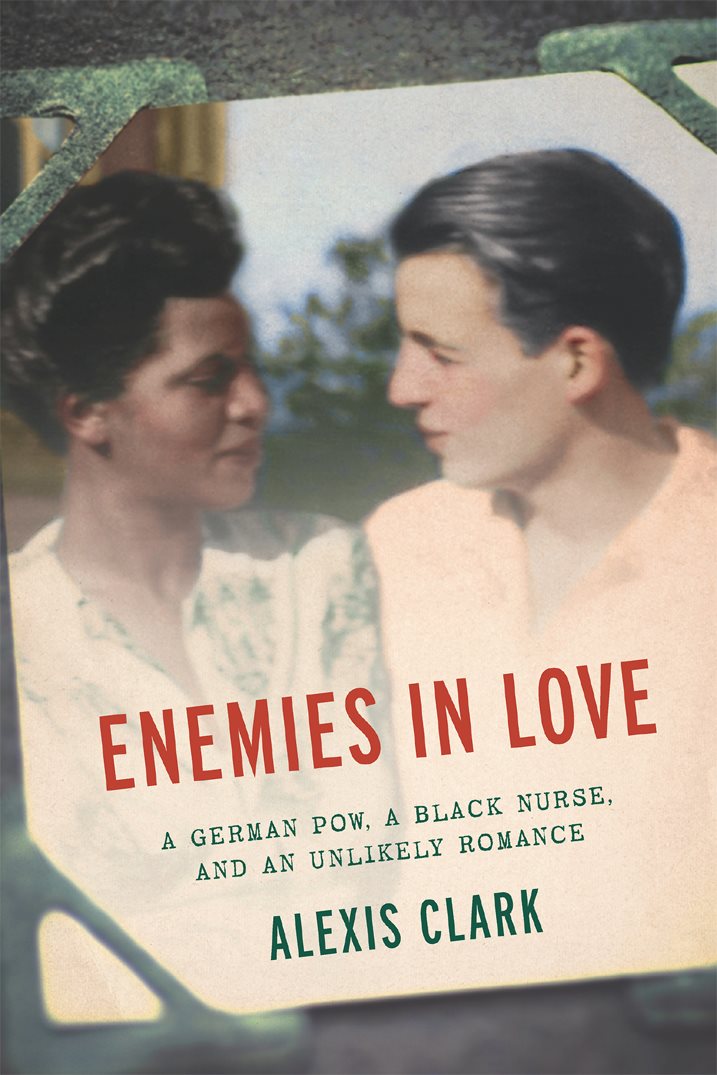

THIS IS THE NONFICTION LOVE STORY OF ELINOR Powell, an African American army nurse, and Frederick Albert, a German prisoner of war. The two met when black army nurses were put in regular contact with German POWs who were detained in the United States during World War II, an unlikely and little-discussed circumstance during one of the most documented periods in history.

I learned about Elinor Powell Albert in 2008. I became interested in black military history around that time after discovering I was a distant relative of Charles Young, the U.S. Armys first black colonel, the leader of the Buffalo Soldiers, and the highest-ranking black officer in the U.S. Army until his death in 1922.

I stumbled across a brief mention of Elinor in a book by naval historian Barbara Brooks Tomblin called G.I. Nightingales: The Army Nurse Corps in World War II. In a chapter about the integration of black nurses, one line changed every thing I thought I knew about the war: The Florence camp holds special memories for Albert, who met and later married one of the German prisoners interned there. Black nurses in POW camps during World War II? Nazi soldiers in the United States? I was stunned. I contacted Tomblin, who had written the book almost fifteen years prior and had no idea if Elinor was still alive. She had never met her, having found Elinors name on a list of black nurses to whom she sent questionnaires about their war experience. I realized I would have to find out about Elinor some other way because I was definitely not ready to let go of her story.

I knew an abundance of research would be required to uncover the story of Elinor and Frederick Albert, who were both deceased. Fortunately, after describing my project and presenting a proposal to the Ford Foundation, I was awarded a series of grants. Soon after, I embarked on my research, tracking down relatives and friends in the United States and Germany, as well as sorting through historical documents. This book is the result. Every scene and conversation is drawn from the countless interviews I conducted with surviving family members and friends. Any conjecture is based on plausible scenarios supported by exhaustive archival research, including oral histories, letters, and military records. In 2013 I wrote an article about Elinor and Frederick for the New York Times, and the idea to expand their story into a book came shortly after.

As a black woman from Texas who was educated in predominantly white schools and at one point lived in a mostly white neighborhood, though my father grew up in Jim Crow Louisiana, I felt a connection to Elinor, and I wanted to know everything about her. What was it like to be an African American nurse in a segregated state? How did she cope with being humiliated and mistreated by whites as an adult when, as I later discovered, her upbringing was filled with positive interactions with white people? How was it possible to love a man who was raised in a country that believed the Aryan race was superior?

Many questions remain unanswered about Elinor and Fredericks relationship and experiences in their respective armies. They were private, even reticent with their children about the war years. But their story reveals a largely unknown and tremendously compelling aspect of military history and race relations in this country. It filled me with a sense of duty to document not only her journey but the period and place in which Jim Crow and Nazism collided and the very unlikely love story it spawned that lasted more than fifty years.

ELINOR POWELL PULLED OPEN THE HEAVY GLASS doors and walked into the massive Woolworths department store on Phoenixs East Washington Street. She adjusted her uniform, tugged at her jacket to air out some of the sweat that drenched her back, and walked to the edge of the lunch counter.

She could feel several white faces glaring in her direction as she stared straight ahead, waiting for the server to approach.

You cant sit here.

Id like a ginger ale, please, Elinor said, ignoring his comment.

I said you cant sit here. No Negroes at the counter. The diners became silent.

Excuse me, sir. Im an American citizen and an officer in the United States Army Nurse Corps. Id like to order a ginger ale, Elinor responded, trying to contain her emotions.

I dont care who you are. If you dont leave, Ill call the police.

Elinor felt the tears forming in the corners of her eyes, but there was no way she would break in front of this racist simpleton and a roomful of unsympathetic patrons.

She was off duty and hoping a day to herself would clear her mind. There werent any critical cases at the hospital, and there were enough nurses on call to handle an emergency if one arose. The German prisoners of war detained at Camp Florence were faring just fine, in Elinors eyes. In fact, they were treated better by Arizonans than were African Americans wearing U.S. military uniforms.

All she wanted was an ice-cold soda. The temperatures in Florence were well over 90 degrees, and the hour-long commute to Phoenix made her delirious with fantasies of sipping a cool drink at the downtown lunch counter. The United States Army Nurse Corps clearly hadnt considered ventilation in their uniform design. The sturdy jacket and skirt, and hat, along with the long-sleeved blouse and nylons, were a torturous ensemble in August.

Elinor saw a menu on the counter, picked it up, and threw it on the floor before storming out. If a glass had been sitting there, she would have thrown that instead. She didnt know where she was going. Her legs and brain hadnt connected yet. But she felt the tears falling off her face, which made her more enraged. There was a small restaurant not too far away. Elinor walked in and pretended not to see people stop talking in midsentence when she approached the counter. May I help you? asked a young waitress. It had been a long time since someone asked her that. Relieved, Elinor sat down, smiled, and asked for a ginger ale.