Pagebreaks of the print version

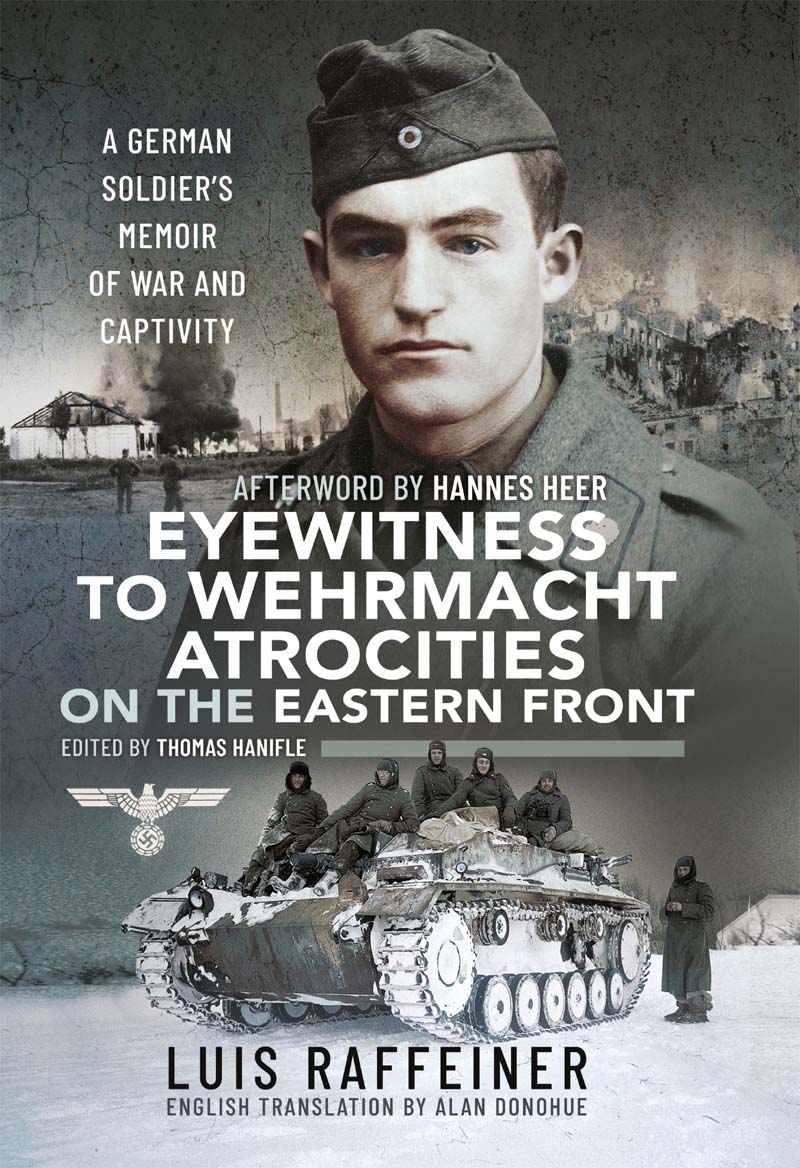

Eyewitness to Wehrmacht Atrocities on the Eastern Front

Eyewitness to Wehrmacht Atrocities on the Eastern Front

A German Soldiers Memoir of War and Captivity

Luis Raffeiner

Transcribed by Luise Ruatti Edited and with a Foreword by Thomas Hanifle English translation by Alan Donohue Afterword by Hannes Heer

First published in Great Britain in 2021 by

PEN & SWORD MILITARY

an imprint of Pen & Sword Books Ltd

Yorkshire Philadelphia

First published in German by Edition Raetia, Bozen/Bolzano in 2010

Copyright German edition, Edition Raetia, Bozen/Bolzano 2010

Copyright English translation, Pen & Sword Books 2021

ISBN 978-1-39909-770-3

eISBN 978-1-39909-771-0

Mobi ISBN 978-1-39909-771-0

The right of Luis Raffeiner to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the Imprints of Aviation, Atlas, Family History, Fiction, Maritime, Military, Discovery, Politics, History, Archaeology, Select, Wharncliffe Local History, Wharncliffe True Crime, Military Classics, Wharncliffe Transport, Leo Cooper, The Praetorian Press, Remember When, White Owl, Seaforth Publishing and Frontline Books.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LTD

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

or

PEN & SWORD BOOKS

1950 Lawrence Rd, Havertown, PA 19083, USA

E-mail:

Website: www.penandswordbooks.com

Foreword: Talking about the war

by Thomas Hanifle

A macabre spectacle: two Russian men and a woman dangle from the gallows in the main square of the Russian town of Maloarchangelsk. Men of the German Wehrmacht have hung a sign around their necks that reads in Russian: This is how partisans end up. This is what happened in March 1942, with the camera held by Luis Raffeiner. Though photographing such scenes had been strictly prohibited by the Nazi regime, many of the German photographers in uniform nevertheless felt magically drawn to the atrocities in this war of extermination against Russia. The soldiers were unlikely to have been strictly supervised in any case. This is also suggested by recent photographic exhibitions in Germany, which hark back to such snapshots taken by former soldiers that until recently were gathering dust in attics or junk rooms.

In any case, Luis Raffeiner had no problems getting back home safely the film rolls and photos he exchanged with comrades or received from officers. Like treasure, he kept the photo material and other mementos of the Option film rolls developed during the war he had usually commissioned comrades who were on home leave in Germany to do it. However, after the war he had entrusted around twelve rolls of film Raffeiner reckons over 200 photographs to his cousin, from whom he had also received the camera and the assignment to record impressions of the war. He got only part of the collection back, and then only after the death of the staunch Nazi. But these are only the harmless photos, Raffeiner is convinced, and assumes that his cousin destroyed the remaining photos.

He could not remove the memories of what he had experienced, for these were burned indelibly into his mind. After returning home from the war, he told his family about them again and again, and every so often his acquaintances and friends too. At least, he told them those bits that he wanted to and could tell other people about. Even today, when recounting the stories, he takes refuge in saying You cant imagine it when he has pictures before his eyes and cannot put them into words. Or he falls into the role of the observer who was not directly involved. From hints and insinuations, however, one can get an idea of how close Raffeiner must also have been to the brutal events, even if his memory sometimes lets him down after almost seventy years. By talking about the war, Luis Raffeiner tries to this day to come to terms with his traumatic experiences. In the immediate post-war period, however, hardly anyone wanted to hear about it everyone was happy that the war was over. Raffeiner concentrated on his new life.

Decades later, two key experiences followed: in 1989 Raffeiner visited the Option exhibition in Bozen/Bolzano, Tyrolers who had said no to the Nazi state were considered by public opinion to be shirkers. Only after the publication of Thalers memoirs in book form and the public discussion about them did the conscientious objectors receive a moral rehabilitation and, indeed, they became a symbol of the resistance. Raffeiner felt forgotten once more. Thalers ordeal and, above all, the attention he received pushed Raffeiners own fate even further into the background. He read Thalers life story as a counterpart to his own: here a remainer, there a person opting to leave; here a deserter, there a combatant; here an anti-fascist, there a Nazi; here a hero and what was he? He had been through a lot in the war and then especially in captivity. And he had never had anything to do with Hitler. According to Raffeiner, his own ordeal ought to have its place in history too.

During this time he set out his life story to Luise Ruatti, a young woman from Naturns/Naturno; they knew each other from their joint involvement in the local theatre association. Ruatti was impressed. Above all, she realized how little she and many of her generation knew about this part of (South Tyrolean) history. Thus, almost fifteen years ago she came up with the idea of recording Raffeiners life for posterity. For two days they both holed up in the cramped, dark room of the local parish broadcaster Sankt-Zeno-Funk. Raffeiner explained that Ruatti recorded his memoirs on tape and gradually put them down on paper, from which this book has now appeared in revised form. The result is an important document for contemporary history that deserves to be emulated, especially since the war generation is slowly dying out. In every village there are contemporary witnesses who still have a lot to tell and in whose attics there is probably illustrative documentation that tells its very own story.

The Hamburg historian Hannes Heer, who caused a sensation in Germany in 1995 as director of the exhibition War of Extermination: Crimes of the Wehrmacht 19411944, was also won over for the present book project. Having read the manuscript, Heer agreed to make a historical classification of the memoirs but not without first speaking to the protagonist himself. For two days he sat with the 93-year-old Raffeiner, reconstructed his units combat route with him, questioned discrepancies and confronted him with the horrors of this cruel war. His conclusion was that Raffeiner was no saint, as this war of extermination had made him both a victim and a perpetrator at the same time. But in spite of everything he remained decent and after the war he had the courage to bear witness to the crimes that he saw, said Heer to one of Raffeiners sons following the meeting. Luis Raffeiner has thus found his place in history.