Contents

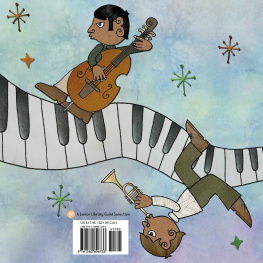

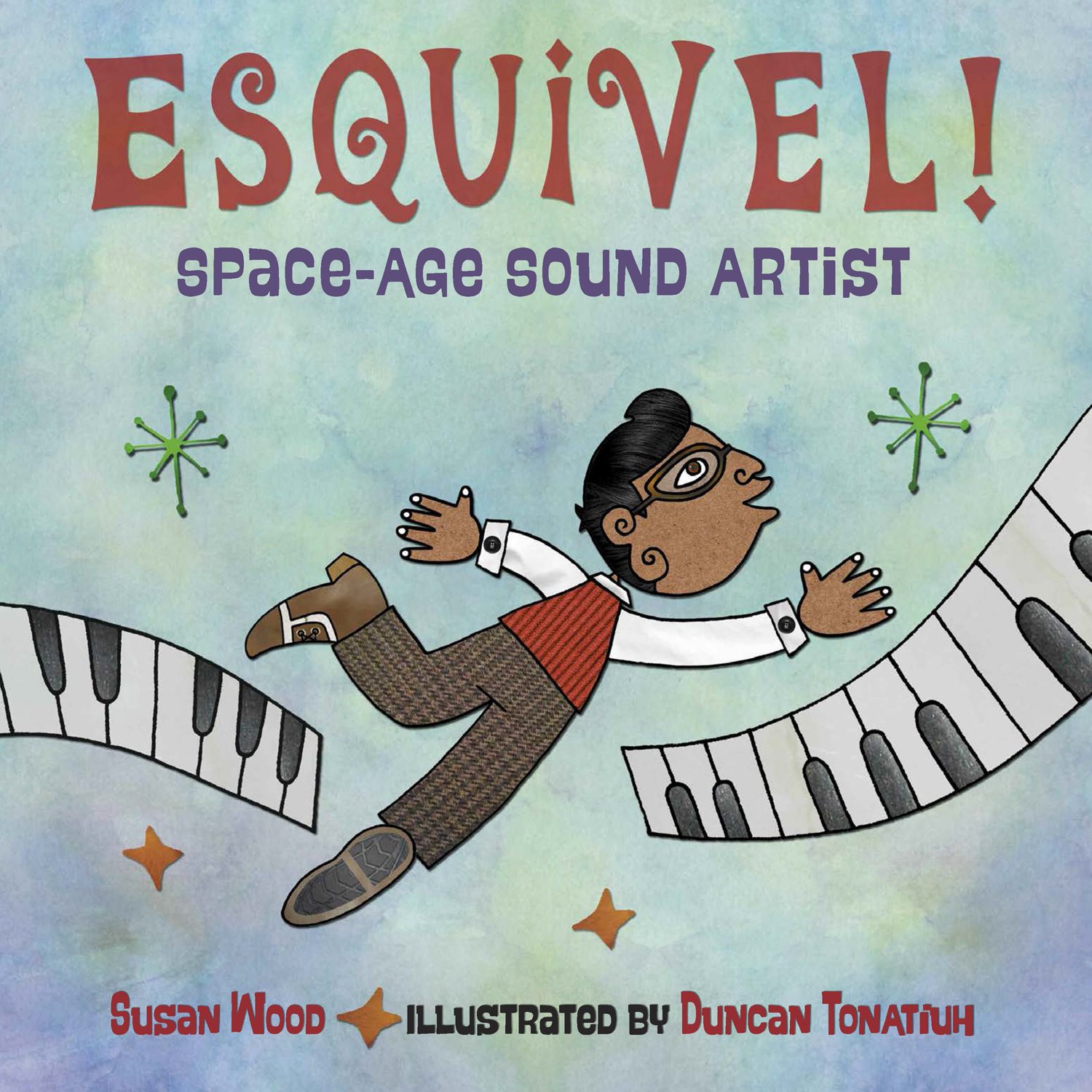

W hen Juan Garca Esquivel was a small boy, he lived with his

family in Tampico, Mexico, where whirling mariachi bands let out

joyful yells as they stamped and strummed.

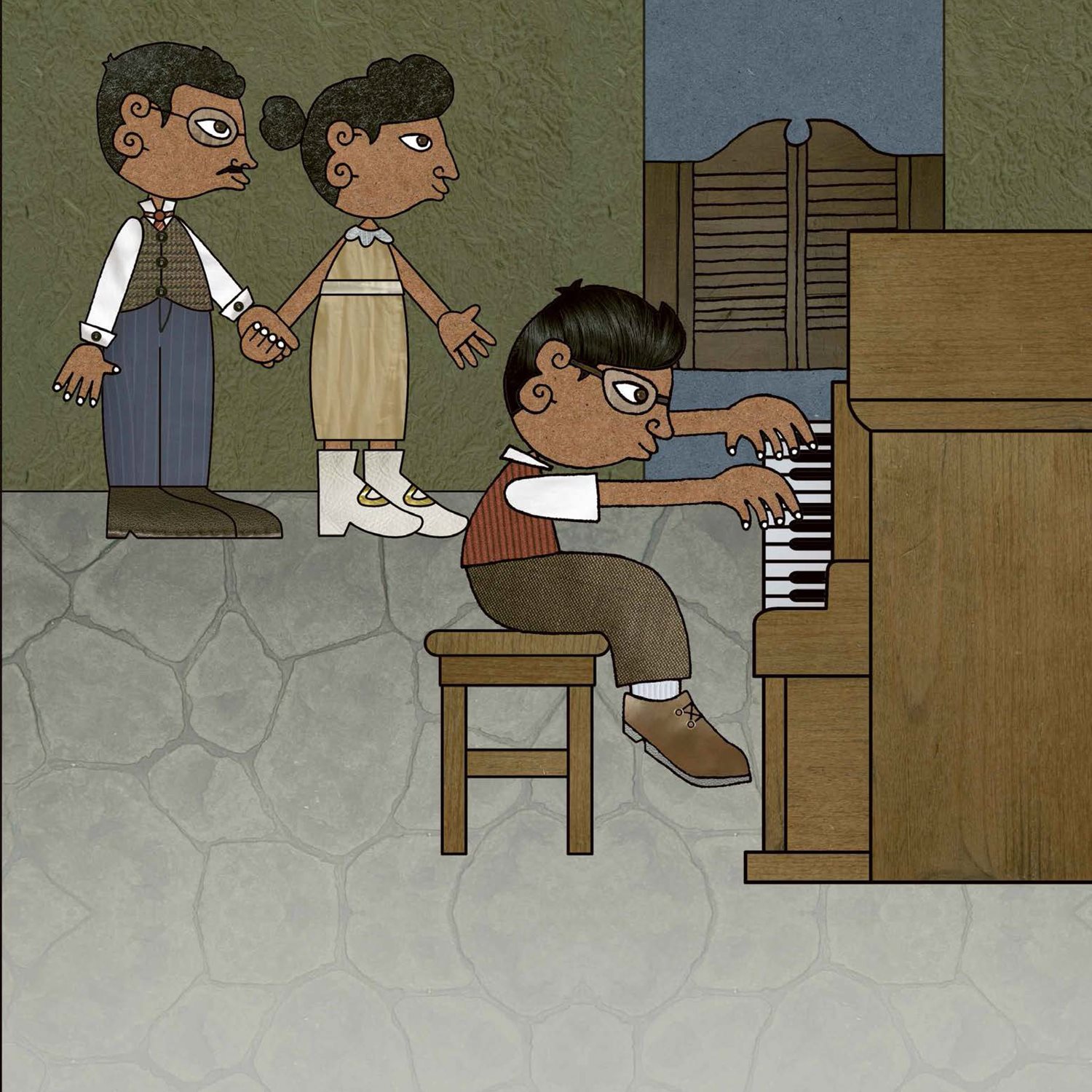

By age six, Juan was curious about music. There was a piano at Juans

house, but it was a player piano a paper roll told it which keys to play.

Clever Juan had an idea. He disabled the paper roll and turned his parents

jangly piano into one he could practice on. He played it day and night.

By age ten, Juan was captivated by music. He loved to play

piano anytime, anywhere. Sometimes hed disappear from home

in search of an audience, and his family would have to go looking for

him. They always found him in front of a piano.

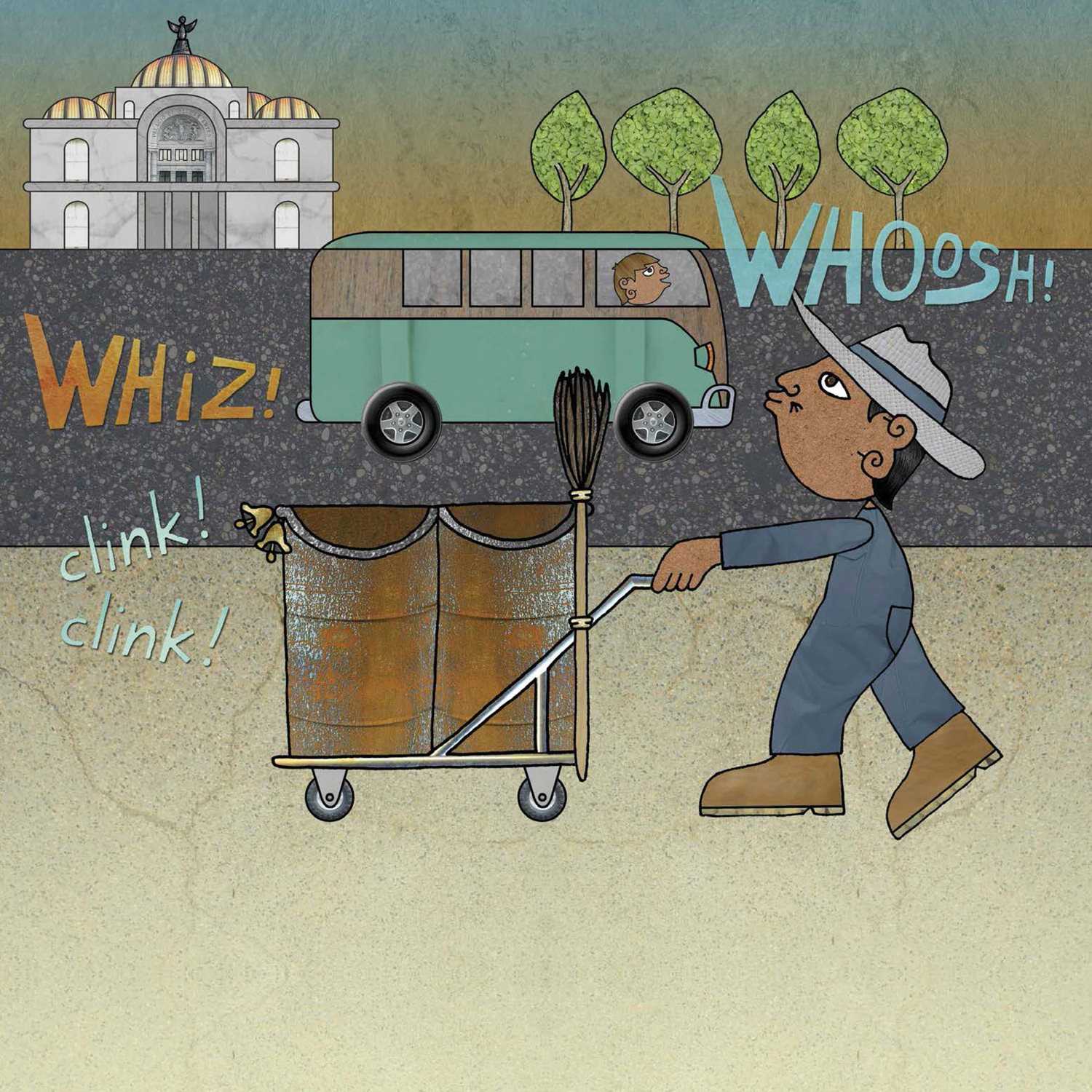

When Juans family moved to Mexico City, the countrys bustling capital,

Juan found work playing piano at Mexicos f irst twenty- four- hour radio station.

He performed for f i f teen minutes each day and was paid two pesos a show

enough to buy a sandwich and a taxi ride home. He was just fourteen years old.

Juan started learning all he could on his own no music teachers, lessons,

or schools. Without traditional training in how musical notes went together,

Juan focused instead on how sounds could be arranged. Finally, Juan felt ready to

create his own music. So when at age seventeen he was offered the job of orchestra

leader for a popular comedy show at the radio station, Juan gladly took it.

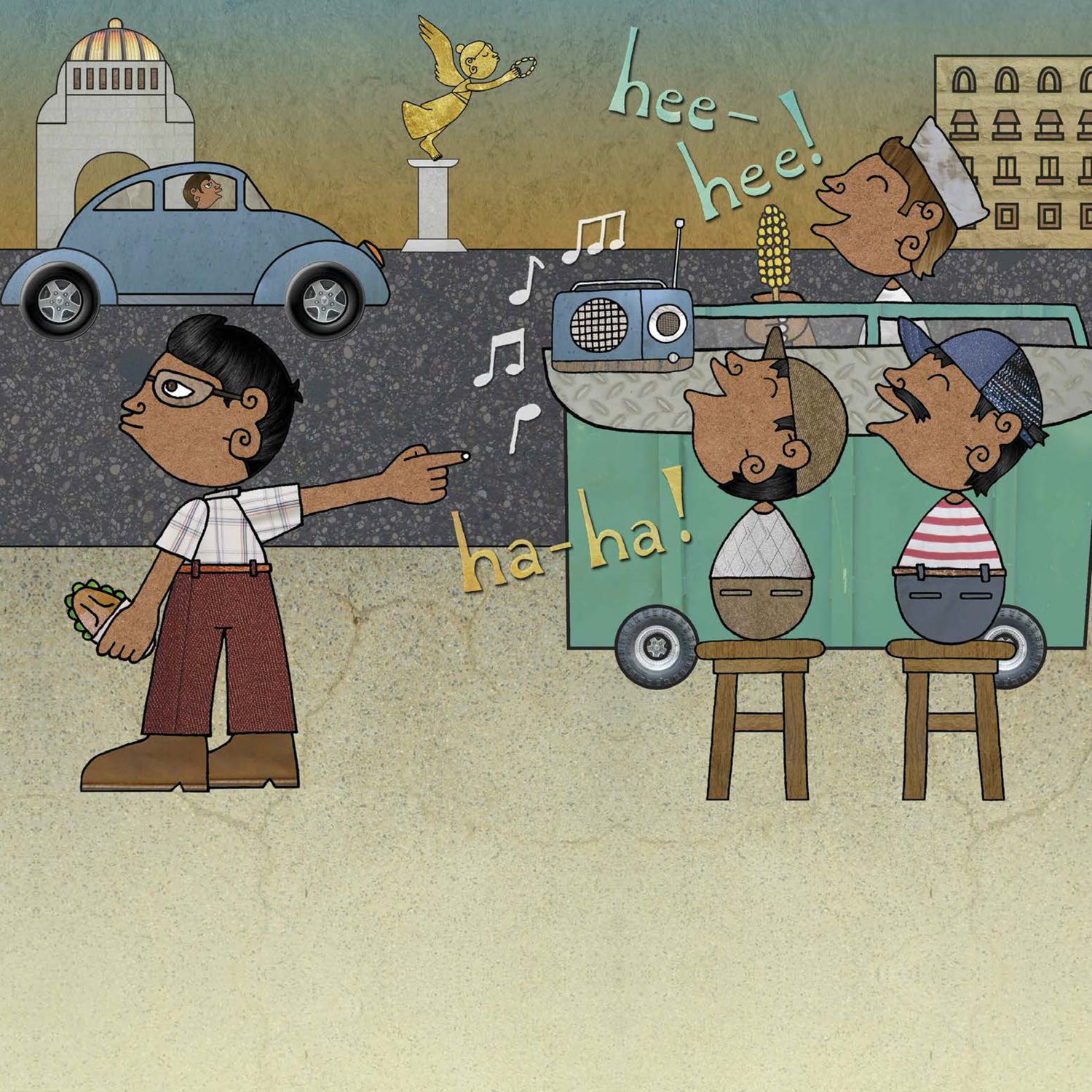

When the radio comedian needed music for a skit about, say,

a stout man walking his tiny poodle down a busy city street, Juan had

to imagine what that might sound like.

Juan might ask the kettle drums to BOWM- BOWM!

BOWM- BOWM! like a lumbering giant.

He might ask the clarinets and oboes to YIP! and YAP!

like a dainty dog.

He might tell the trumpets and trombones to HONK! BLAP!

BLEEP! like blaring car horns.

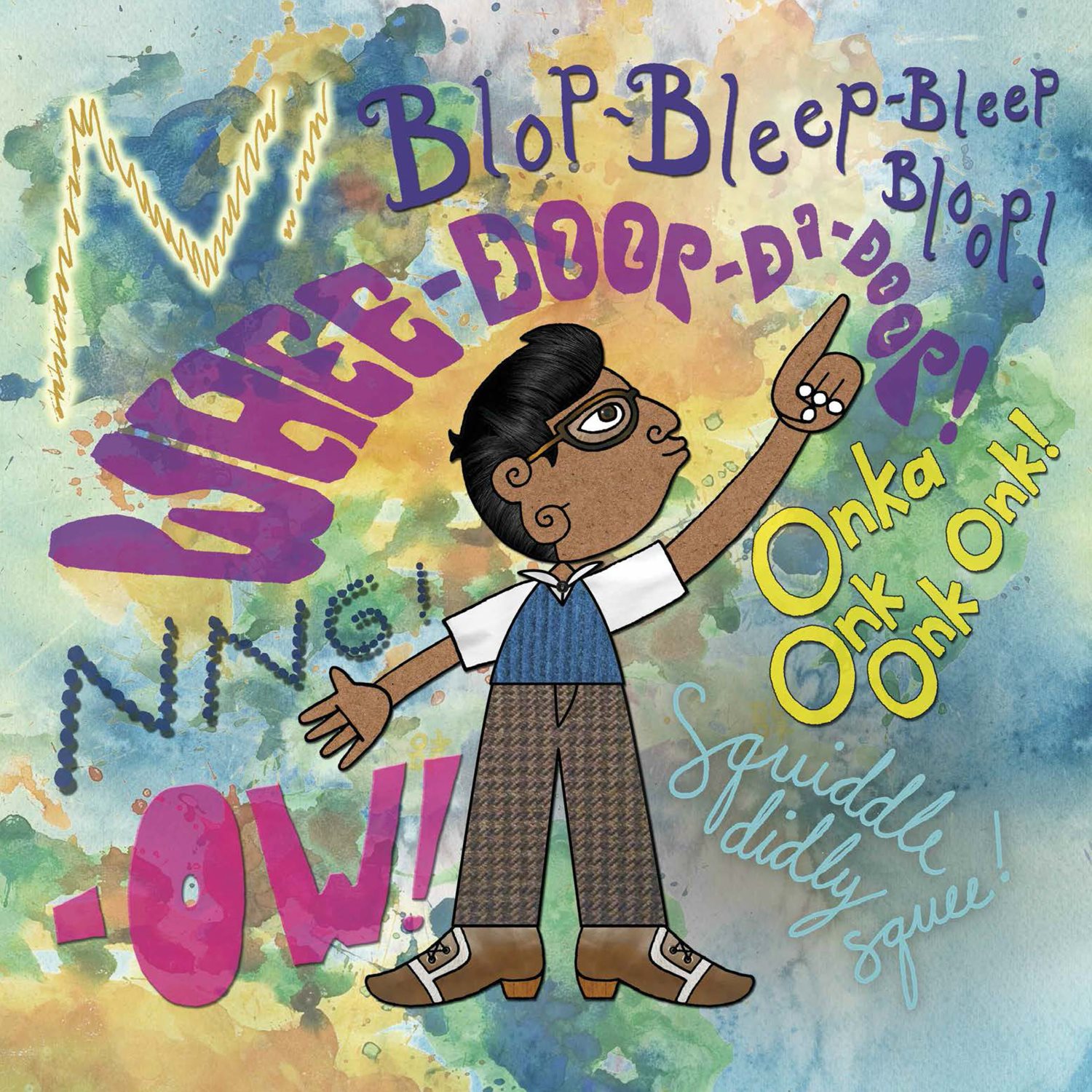

Juan tested and mixed and blended and arranged all sorts of sounds

to match the imaginary situation. He was an artist, using dips and dabs

of color to create a vivid landscape. But instead of paint, Juan used

sound. Weird and wild sounds! Strange and exciting sounds!

Juan started experimenting with popular Mexican tunes. He tinkered

with tempos, slowing songs down, then revving them up. He f iddled with

dynamics, swapping soothing so f t sounds and startling loud sounds.

He twisted chords and combined instruments to sound thrilling, dreamy,

and o f ten funny, because Juan liked music that made people laugh.

But underneath the humor, it took great musical skill to play Juans

challenging new music.

Nobody had ever heard music like Juans. Soon he was winning

awards. His songs were turned into records that people could buy in

stores. Juans innovative music could be heard on radios and record

players all across Mexico.

An important record company in the United States heard about

Juan and his unusual music. Would he come make records in America?

Yes! Yes! Yes!

Juan packed two suits. He bought a big red convertible sports car with

a white top. Then he drove all the way to New York City.

There Juan found a music shop the size of a department store,

with three entire f loors full of strange and exotic instruments.

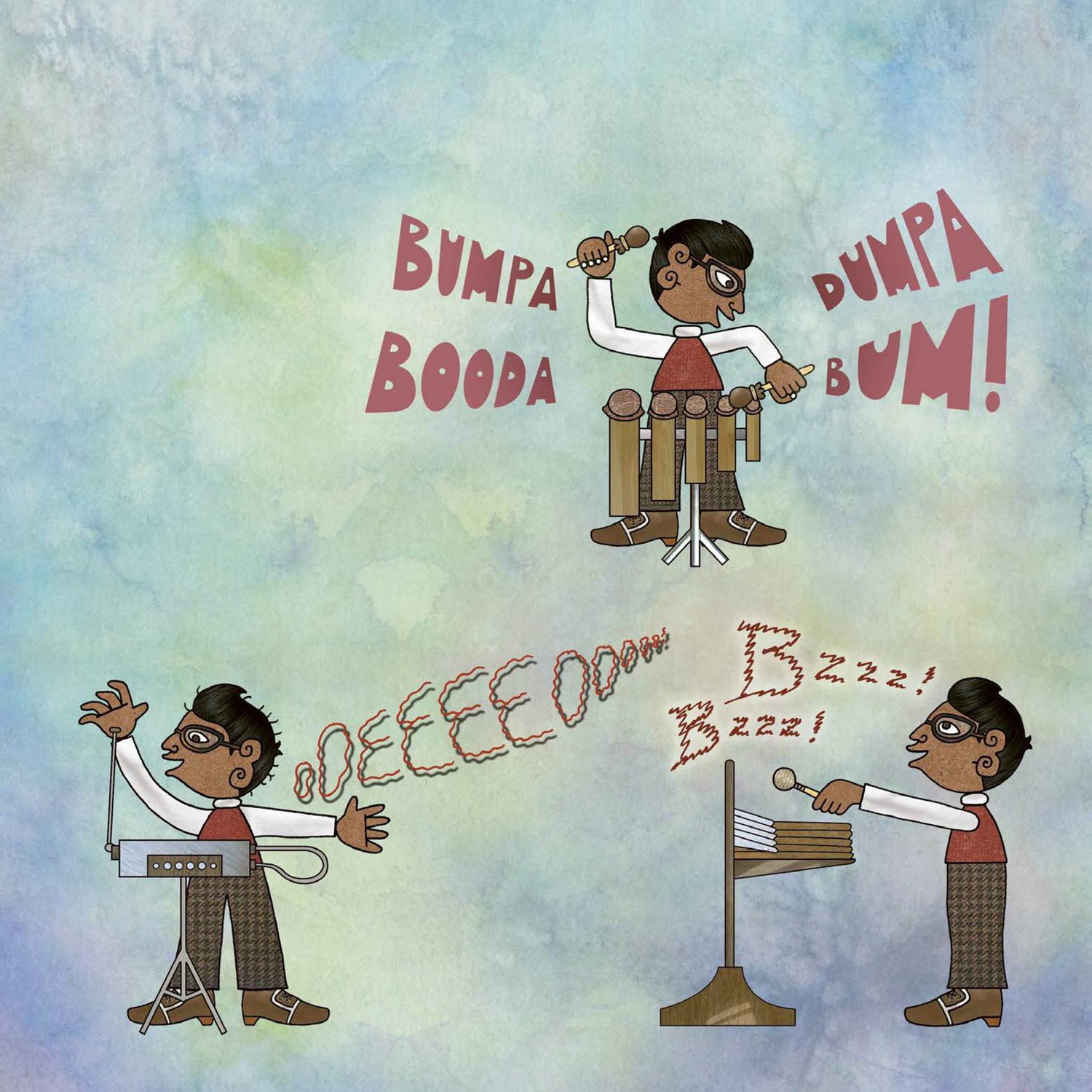

He saw

boobams ,

bamboo tubes that

could play a tune,

a spooky- sounding electrical

instrument called a

theremin ,

a buzzimba , a kazoo-

sounding contraption played

with a mallet,

the ondioline ,

an organ with a swaying

keyboard,

and even a giant gong .

So many odd, new sounds to play with Juan was in heaven!

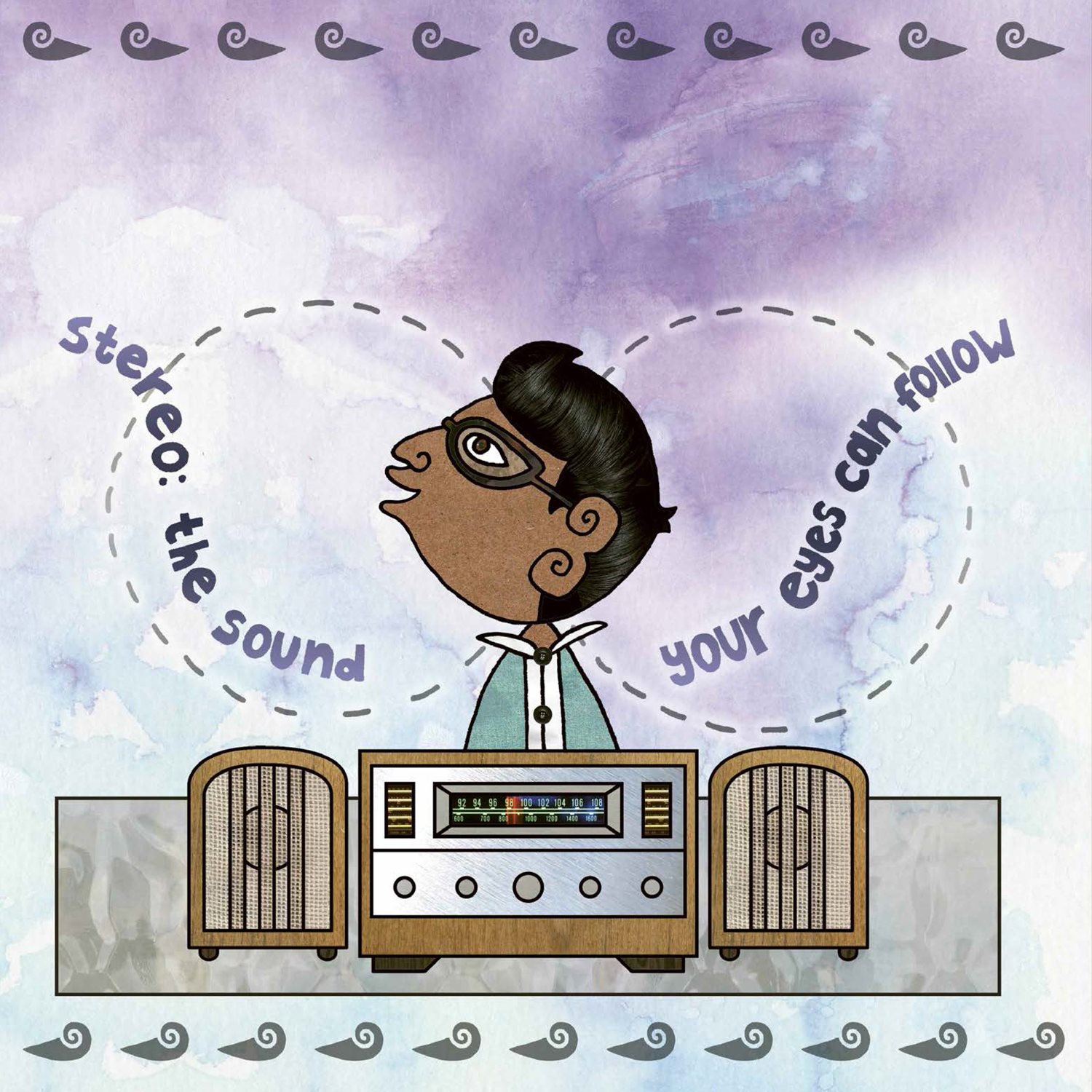

The late 1950s and early 1960s was a great time to be recording music.

Scientists had discovered a new process called stereophonics, or stereo for

short. It separated sounds so when you listened to a recording, music could

seem to come from the left side, the right side, or both sides at once. For

sound artist Juan, stereo was yet another exciting color for his musical palette.

To make a good stereo recording, instruments needed to be kept apart while

they were recorded. That way, the BRAP! of the horns wouldnt get mixed in

with the WHEEDY- WHEE! of the f lutes. Most conductors used curtains,

screens, or special booths to separate the instruments. That wasnt enough for Juan.

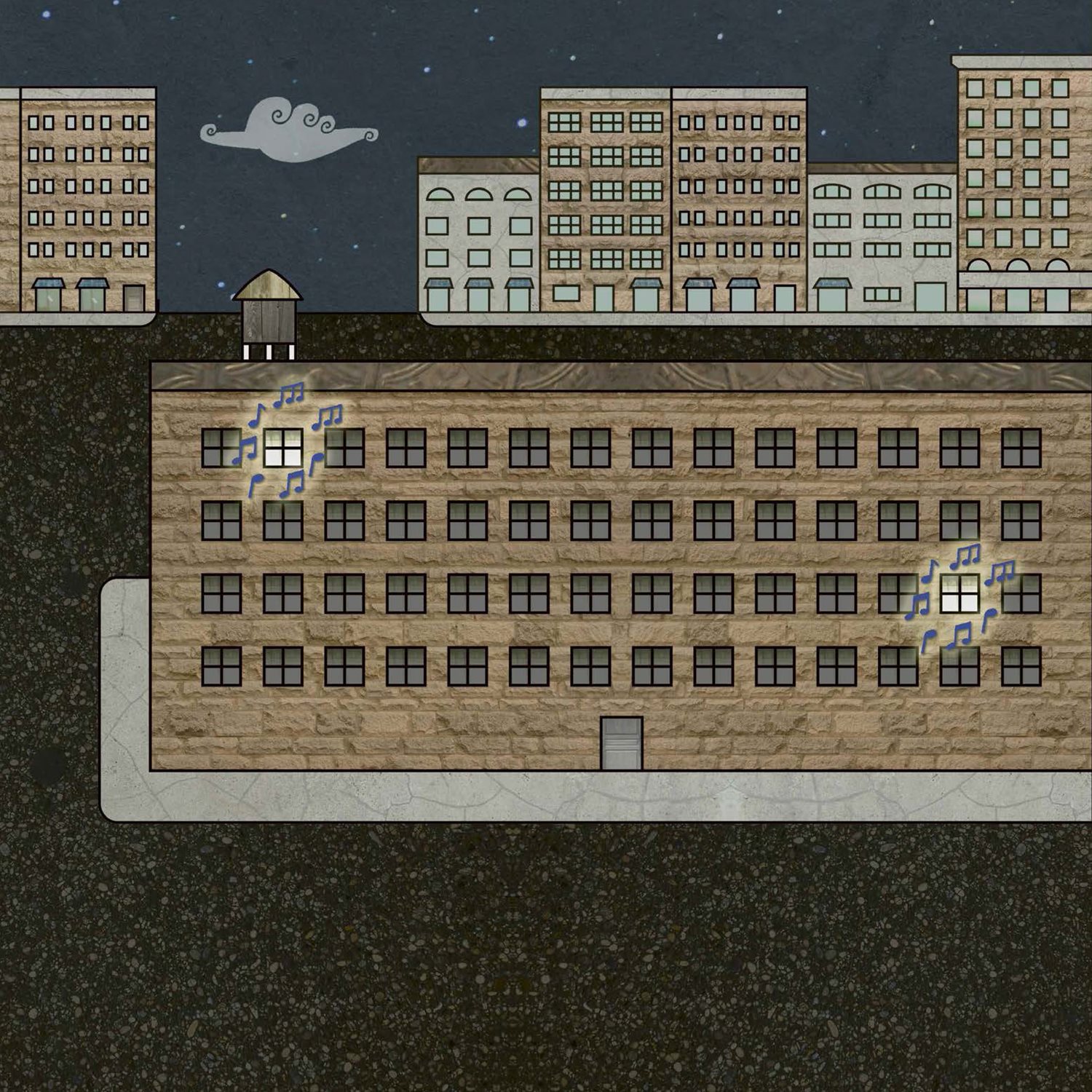

Once he put half his orchestra in one recording studio and the other half...