Preface

Lighthouses are a relic of the past

In an age when satellite technology can lead a mariner to within three feet or less of a buoy in the middle of the ocean, the practical need for a guiding light is pretty well gone. Most mariners dont rely on lighthouses much anymore. Cash-strapped governments dont want to maintain them. This is certainly the case in Canada, where the feds are now in the process of getting out of the traditional-aids-to-navigation business.

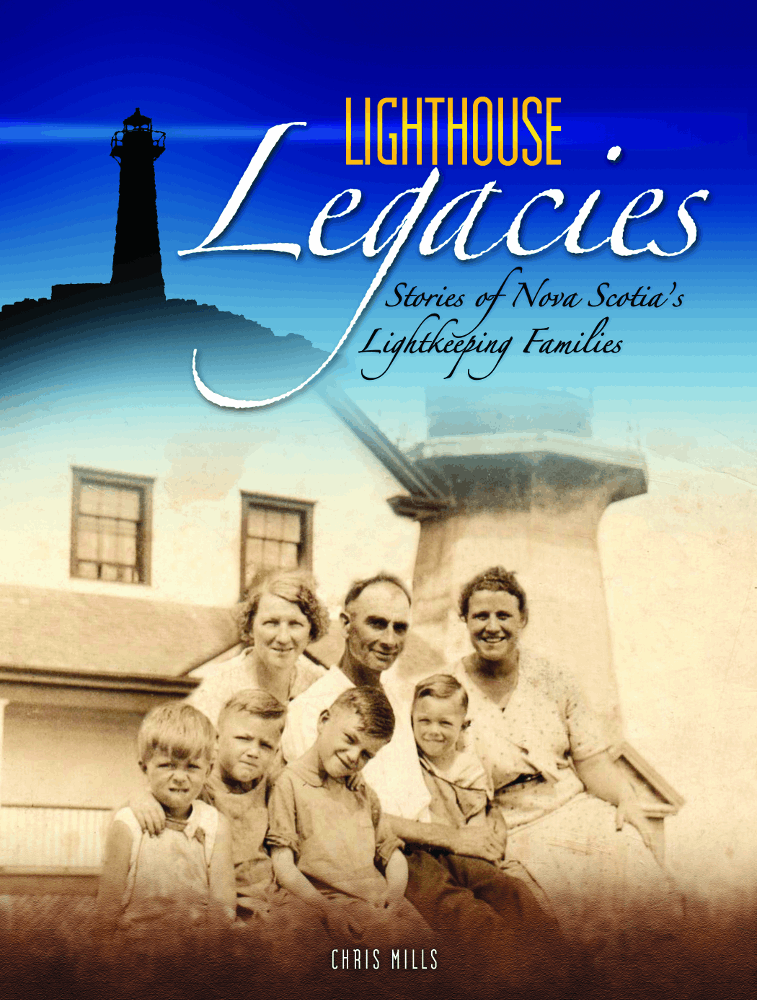

The end result is that lighthouses, already much altered by modernization, automation and neglect, are disappearing. And with them go the lifetimes of experience of hundreds of lightkeepers and their familiesthe very heartbeat of our guiding lights.

When I first got involved in lighthouse preservation more than a decade ago, I thought it would be a noble and wonderful thing to physically save the structures. What better way to spend a life than swinging a hammer and wielding a paintbrush to resurrect a proud sentinel of the sea? I still think its a great idea, but in my case, it would likely mean financial destitution, divorce, and very little personal life other than saving lighthouses. So, my goal is to try to save the memories of the people who lived the lighthouse life. Their experiences are as important as the physical structures they maintained, and their memories are as endangered as the lights they once kept.

Were at a critical point in lighthouse history in Canada as the old-timers die off. In another decade or so, there wont be many people who know just what it was like to climb inside a glittering Fresnel lens, set a match to a kerosene vapour light, or stand on the spokes of a huge flywheel to start a foghorn engine.

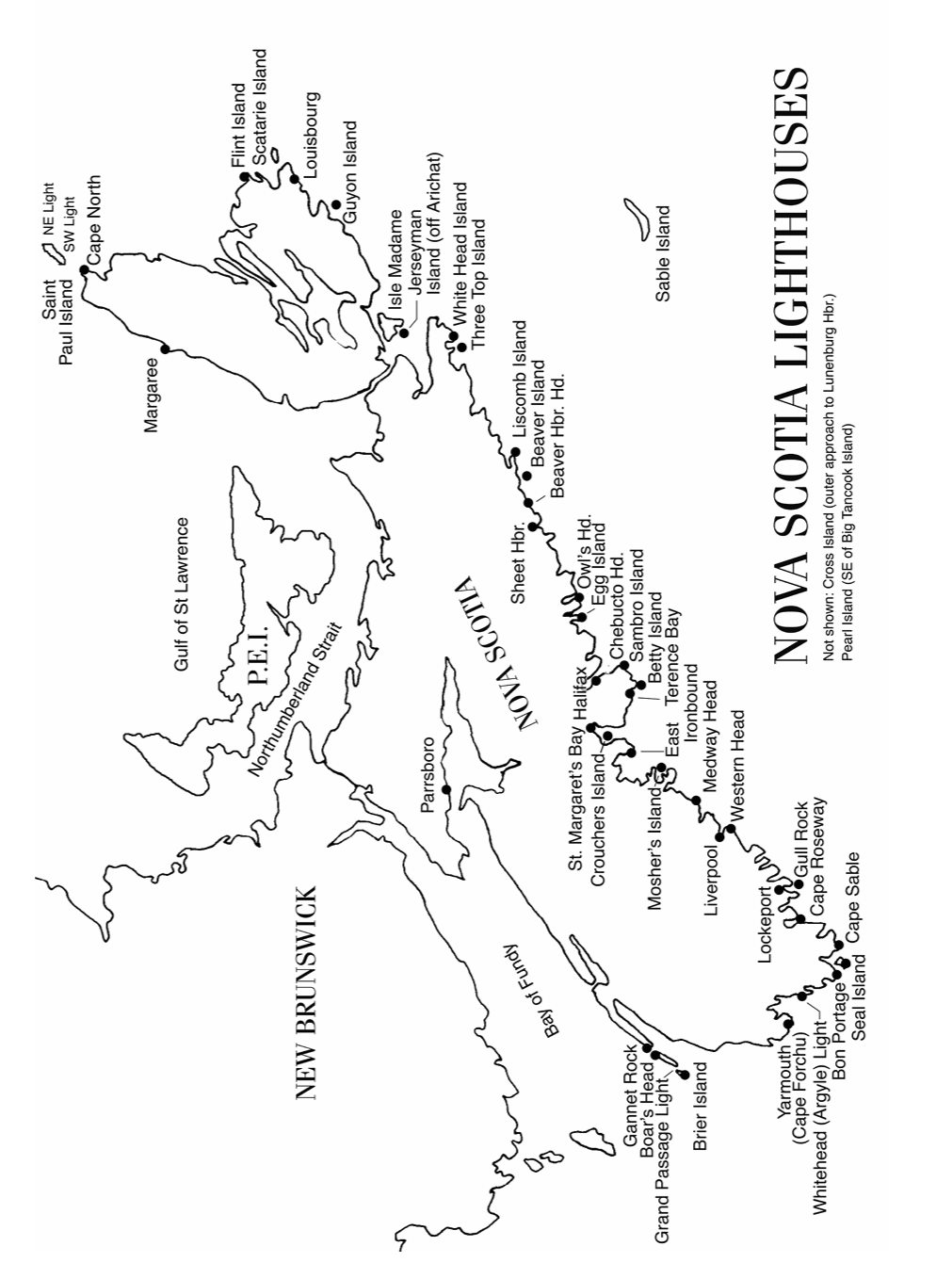

This was the work and the life that sustained thousands of keepers and their families, beginning in 1734, when Canadas first lightkeeper lit the cod liver oil lamp in the great stone tower at Louisbourg, Cape Breton. In Nova Scotia the age of the lightkeeper ended 259 years later, when the last guardians locked up the Cape Forchu light in Yarmouth.

In the fall of 1993, just months after Yarmouths light lost its keepers, I began to interview former lightkeepers and their families as a way of saving their memories from the scourge of automation and mortality. In 2000 I picked up the pace, spurred by the obituaries in the newspaper and by an almost frantic desire to save all that I could of a vanishing way of life.

Some interviewees were friends I had made while I worked as a lightkeeper. Others I met for the first time after tracking them down through phonebooks, local knowledge, and chance encounters.

What emerged from my interviews with these folks was a remarkable series of vignettes of a life now relegated to memory and the occasional article in a newspaper or magazine. As I talked with people, I began to see patterns in their experiences, despite different family backgrounds and life on different lightstations. I decided to run with what I had, arranging stories thematically as a way of exploring lighthouse work and life.

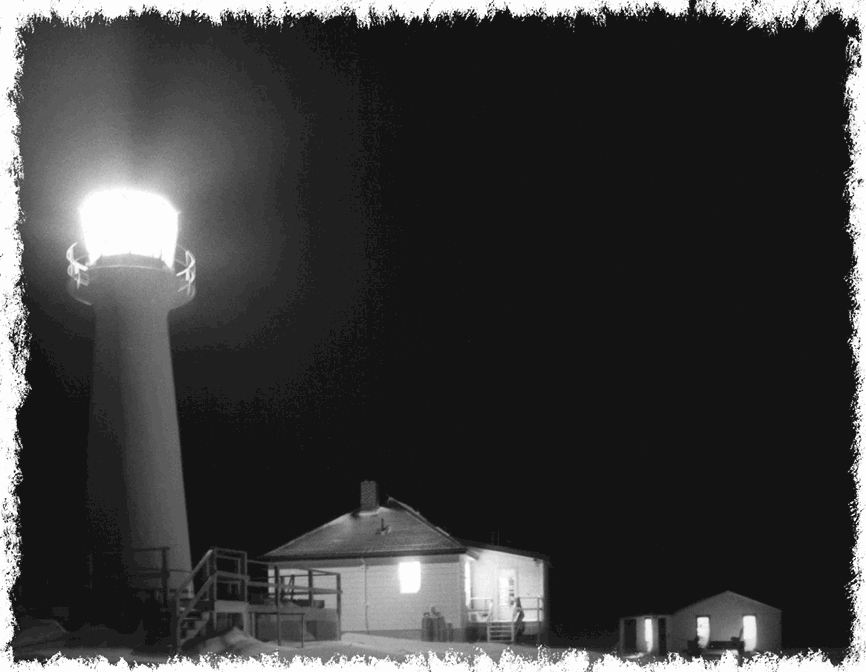

Cross Island, NS, in February 1989, a few months before the last keepers left. (Chris Mills)

The bulk of the interviews cover the period from 1930 to the mid-1980s. Although it seems like a short period of time, that half-century represents almost 250 years of lightkeeping experience; the way of life and the job did not change appreciably until the 1960s, when electrification made life easierand heralded the end of the lightkeeper.

Some people were reluctant to be interviewed, at first. Oh, I dont know anything about the history of the light! What if I cant answer your question? Im not gonna be on camera, am I?

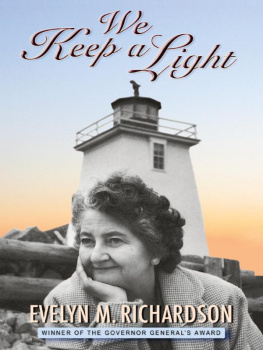

Evelyn Richardsons daughter Anne Wickens wrote me that she would not necessarily be a good candidate for a tape recording. Technical, mechanical and electronic contraptions are anathema maranatha to me, and put me off stride.

But Anne rose to the occasion, sitting for two sessions in front of the mic, arms folded, eyes closed and full of memories of life on Bon Portage Island.

Sometimes I interviewed two or three family members at one time, making for lively conversation as daughters corrected fathers and siblings ribbed each other about goings-on in the old days. These sessions were a nightmare to transcribe, but they are all the more important for their interaction and vitality.

I couldnt use every lighthouse story in the book. Its not for lack of wanting to, but I had so much material that I had to be careful to avoid repetition. (How many times did I hear a keeper or family member say theyd only listen for their foghorn when it stopped blowing?!)

I tried to stay away from a lot of purely technical questions during my interviews. Its not that Im not interested in how the lights were built or what kinds of equipment were used. Im as keen as the next lighthouse nut to talk about the virtues of a third-order Barbier lens over an APRB-252 plastic light.