To Ruth and George Rooks

CONTENTS

...............

...............

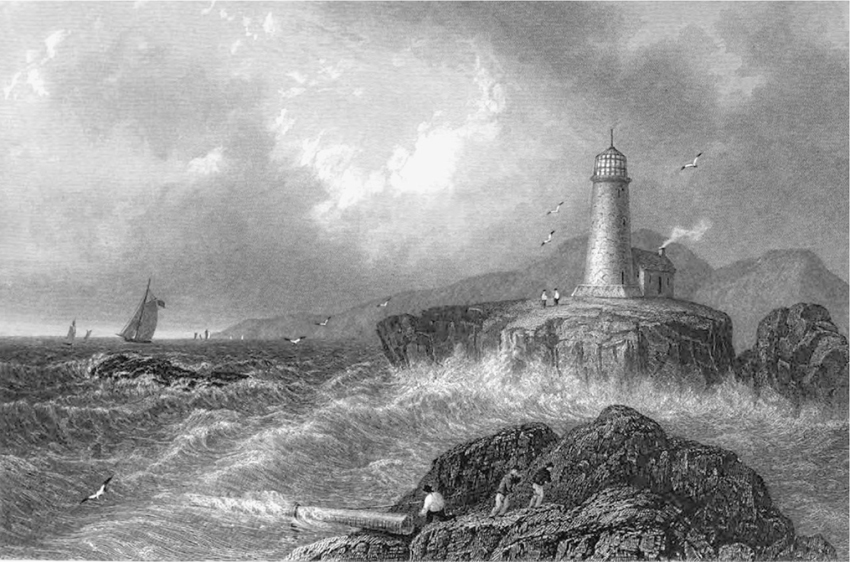

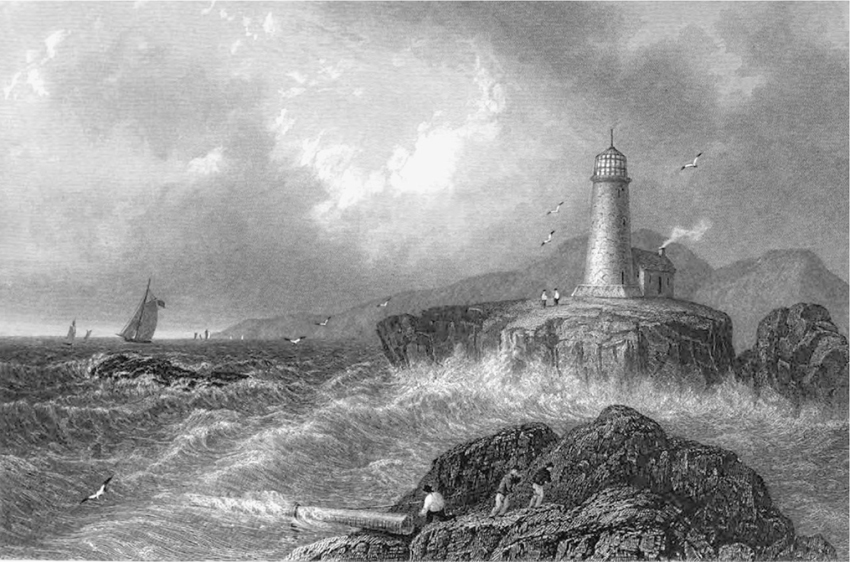

Engraving done in 1840 of Maines Mount Desert Rock Lighthouse, after a painting by Thomas Doughty.

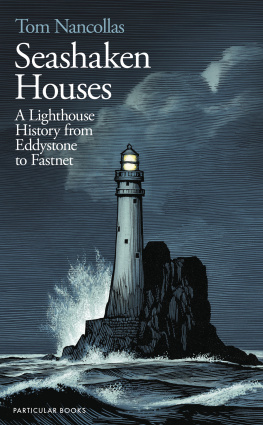

T HE SEA IS A DANGEROUS PLACE, AND THE GREATEST DANGERS loom closest to shore. Although storms imperil mariners wherever they are, they can confidently maneuver their ships on the open ocean without the fear of encountering unseen hazards or running aground. But as ships graze the coast, the risks multiply. That is where jagged reefs, hidden sandbars, towering headlands, and rocky beaches threaten disaster. In the morning hours of February 24, 1817, William Osgood and his small crewaware of such maritime portentswere intently, perhaps somewhat desperately, peering ahead for any sign of light.

Osgood was captain of the Union , a fine three-masted ship out of Salem, Massachusetts, sailing back from Sumatra with a cargo of nearly five hundred thousand pounds of pepper and more than one hundred thousand pounds of tin. A little after midnight Osgood spotted a familiar and most welcome sight. The beams coming from the twin towers of Thacher Island Lighthouse, off Rockport, Massachusetts, told him he was on course, thus nearing the end of his voyage. Osgood ordered his men to steer the ship southwest, keeping an eye out for the lighthouse on Bakers Island, which was not far from Salems wharves. About two hours later they saw the lighthouse gleaming faintly in the distance and headed in that direction, but then a snowstorm obscured their view. When the lighthouse finally reappeared, however, alarm rather than relief seized the men.

When the Union left Salem one year earlier, in 1816, the lighthouse on Bakers Island had two towers, and cast two beams, like the twin lights on Thacher Island. Yet, during the Union s journey, the Bakers Island Lighthouse was modified to exhibit only one light. Osgood and his men knew nothing of this alteration. Therefore, when they saw only a single light, confusion set infollowed by panic. Some of the men thought they must have missed Bakers Island and were instead looking at the single beam of the Boston Lighthouse, which was about fifteen miles south of Salem. Others believed, despite there being only one light, that it must be Bakers Island. But since the ship was very close to the island, there was little time to react. The steersman turned the helm in one direction, thinking it was the Boston Lighthouse in the offing, while Osgood, still certain it was Bakers Island, ordered a different course. But it was too late. Not long after Osgood barked his order, the Union wrecked on the northwest corner of Bakers Island. Mercifully all the men on board survived, and salvage operations later recovered much of the tin and about half of the pepper. The ship, however, was a different story: Insured for $45,000, it was a complete loss.

_____

T HE U NION DEBACLE POINTEDLY illustrates the fundamental purpose of lighthouses, which is to guide mariners safely to their destination. Had the Bakers Island Lighthouse shone two beams that frigid February morning, the Union would not have foundered on the rocks because the men would have known their location and reacted appropriately. The Union disaster notwithstanding, for three hundred years Americas lighthouses have kept countless ships from wrecking, saved untold lives, and contributed mightily to the growth and prosperity of the nation.

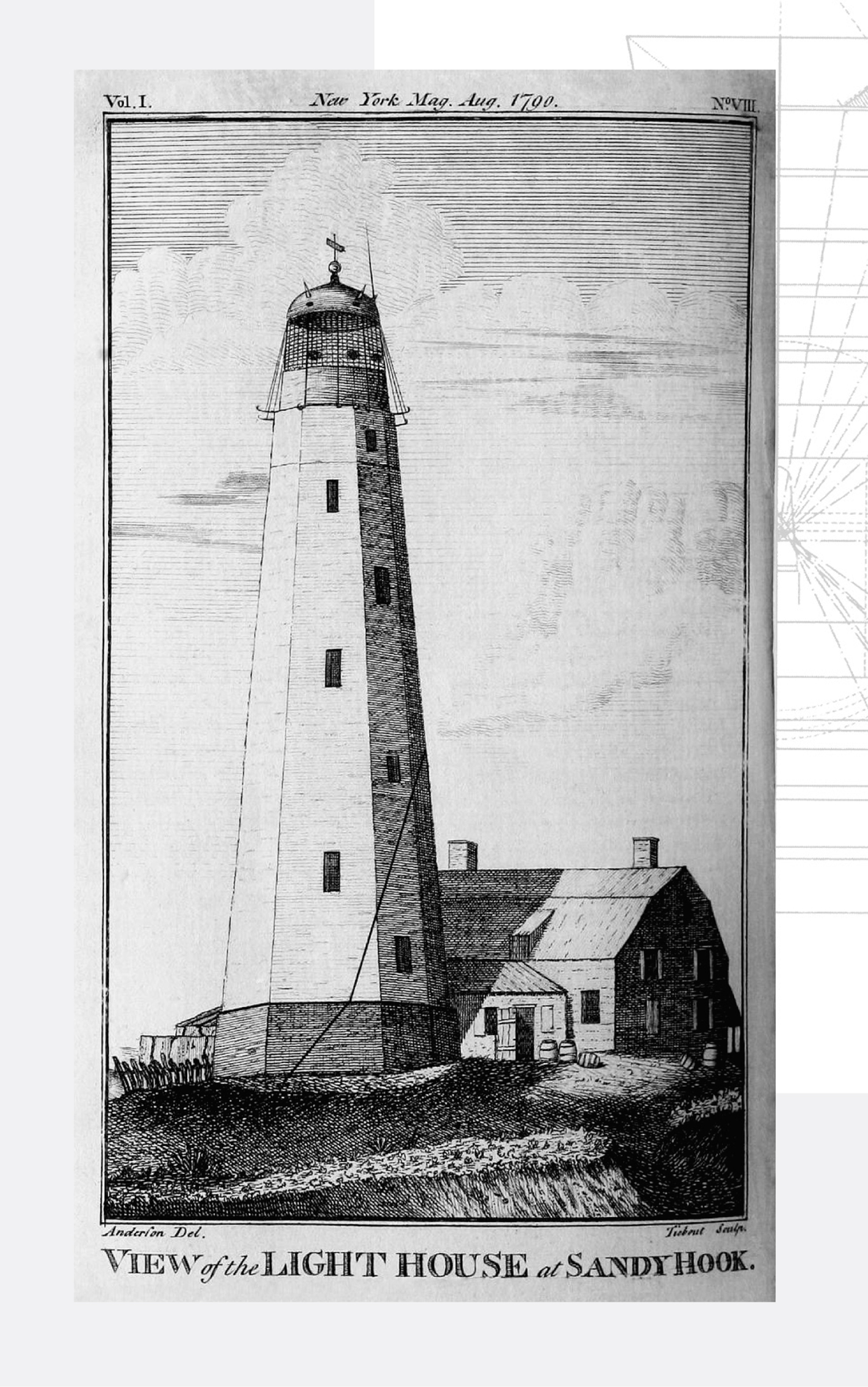

The history of Americas lighthouses is wondrously wide ranging. It is about the farsighted colonies that built the first lighthouses on the east coast to welcome commerce to their shores, embracing the founding of the nation and its dramatic expansion across the continent. When the inaugural federal Congress convened in 1789, one of the first issues it took up was whether the federal government or the states would be in charge of lighthouses; and in one of its earliest acts, Congress made lighthouses a federal concern. From that point forward, as the country grew, so too did the number of lighthouses, creating a necklace of beacons and literally lighting the way for the settlement of new territories and states.

Brilliant Beacons is also a history of government ineptitude and international competition. For a long time Americas lighthouses were vastly inferior to those in Great Britain and France, even though many stubborn and misguided American officials refused to concede that fact. Only by emulating its cross-ocean rivals was America able to elevate its lighthouse system from one mired in mediocrity to one that was among the best in the world.

It is likewise a history of lighting innovation. Lighthouse illuminants changed dramatically over time, running the gamut from whale, lard, and vegetable oil to kerosene, acetylene, and finally electricity. Similarly, crude lamps gave way to more sophisticated ones, and reflectors that did a poor job of projecting the light were replaced by the crown jewels of lighthouse illuminationFresnel lenses, which not only increased the intensity of the light, but also became one of the most important and strikingly beautiful inventions of the nineteenth century. Most of these elegant lenses have since been supplanted by modern optics, which are far less arresting to the eye, yet still effective in casting refulgent beams toward the horizon.

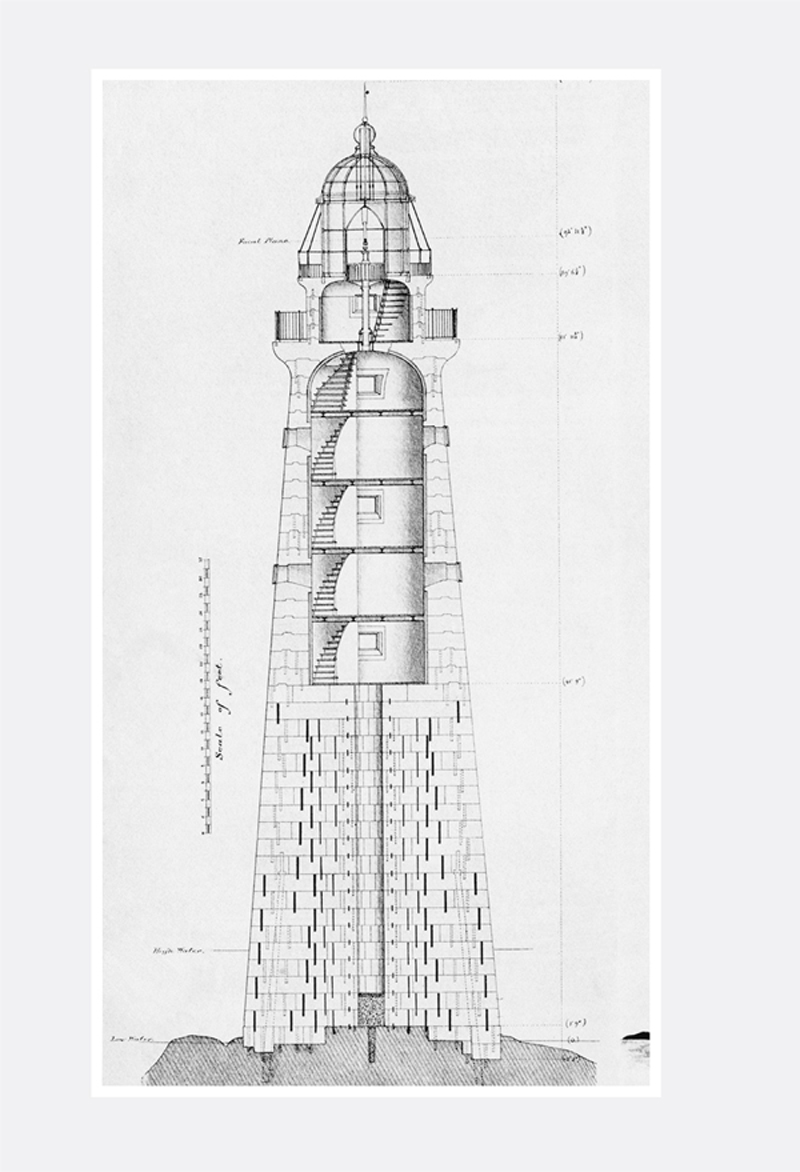

Lighthouses have undergone substantial structural changes. While early towers were made of wood or rubble stone, in later years cut stone, bricks, iron, steel, reinforced concrete, and even aluminum became the materials of choice. Although all lighthouses required skill to build, a few posed such significant challenges that they are truly marvels of engineering, serving as testaments to human ingenuity.

Americas military history is one in which lighthouses have played a crucial role. They served as lookout towers in many conflicts, but during the American Revolution and the Civil War they also became key strategic targets, resulting in more than 160 of them being damaged or completely destroyed.

Like wars, natural disastersespecially hurricaneshave taken a terrible toll on lighthouses. The Great Hurricane of 1938 stands out, both for the extent of devastation it wreaked, and for the gripping and tragic stories of survival and death that it left in its wake.

At its core, however, the dramatic history of Americas lighthouses is about people, and an intriguingly diverse cast of compelling characters brings that history to vivid life. These include Founding Fathers, skillful engineers, imperiled mariners, and intrepid soldiers, as well as saboteurs, penny-pinching bureaucrats, ruthless egg collectors, and inspiring leaders. Undoubtedly the most important actors are the male and female keepers, whooften with the invaluable assistance of their familiesfaithfully kept the lights shining and the fog signals blaring.

No one who has studied the history of these keepers could claim that their lives were a proverbial picnic, for they contended with loneliness, monotony, and a myriad of dangers. Not surprisingly a few died in the line of duty. Many keepers rescued people in distress on the water, some performing so heroically that Americas highest award for lifesaving was bestowed on them. Above all, keepers provided a vital public service that was at once noble and altruistic. As the early-twentieth-century historian William S. Pelletreau stated, Among all the hosts who are called to the service of the government, perhaps none is charged with duties of such moment and of such universal usefulness as is the lighthouse keeper. The soldier and the statesman protect the national honor and the person and property of the citizen, and their acts are performed in the gaze of the world. But the quiet man who trims and lights the shore and harbor lights, and watches them through the long night, stands his vigil for all humanity, asking no questions as to the nationality or purpose of him whom he directs to safety.

Next page