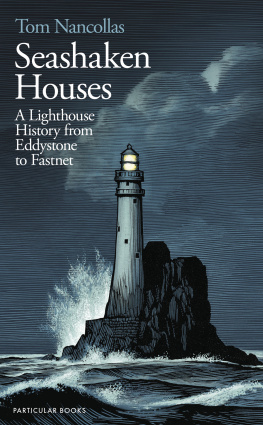

Tom Nancollas

SEASHAKEN HOUSES

A Lighthouse History from Eddystone to Fastnet

PARTICULAR BOOKS

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia

India | New Zealand | South Africa

Particular Books is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

First published 2018

Copyright Tom Nancollas, 2018

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Cover illustration: Chris Wormell

Author photograph: Phil Fisk

ISBN: 978-1-846-14939-9

To Josephine

And to the memory of Jefferson Edward Jones, 19872018

In my seashaken house

On a breakneck of rocks

Dylan Thomas, Prologue, 1952

Introduction

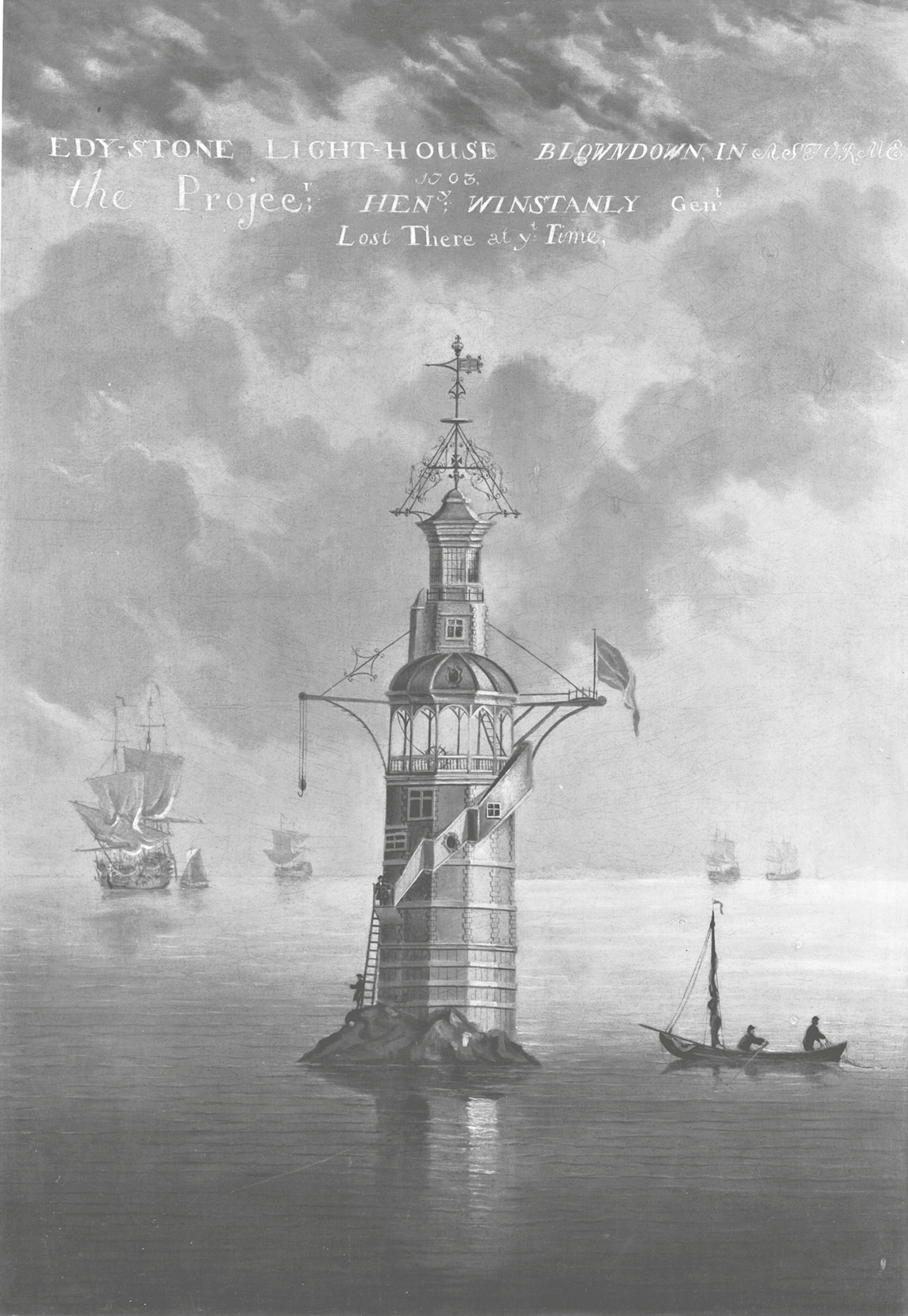

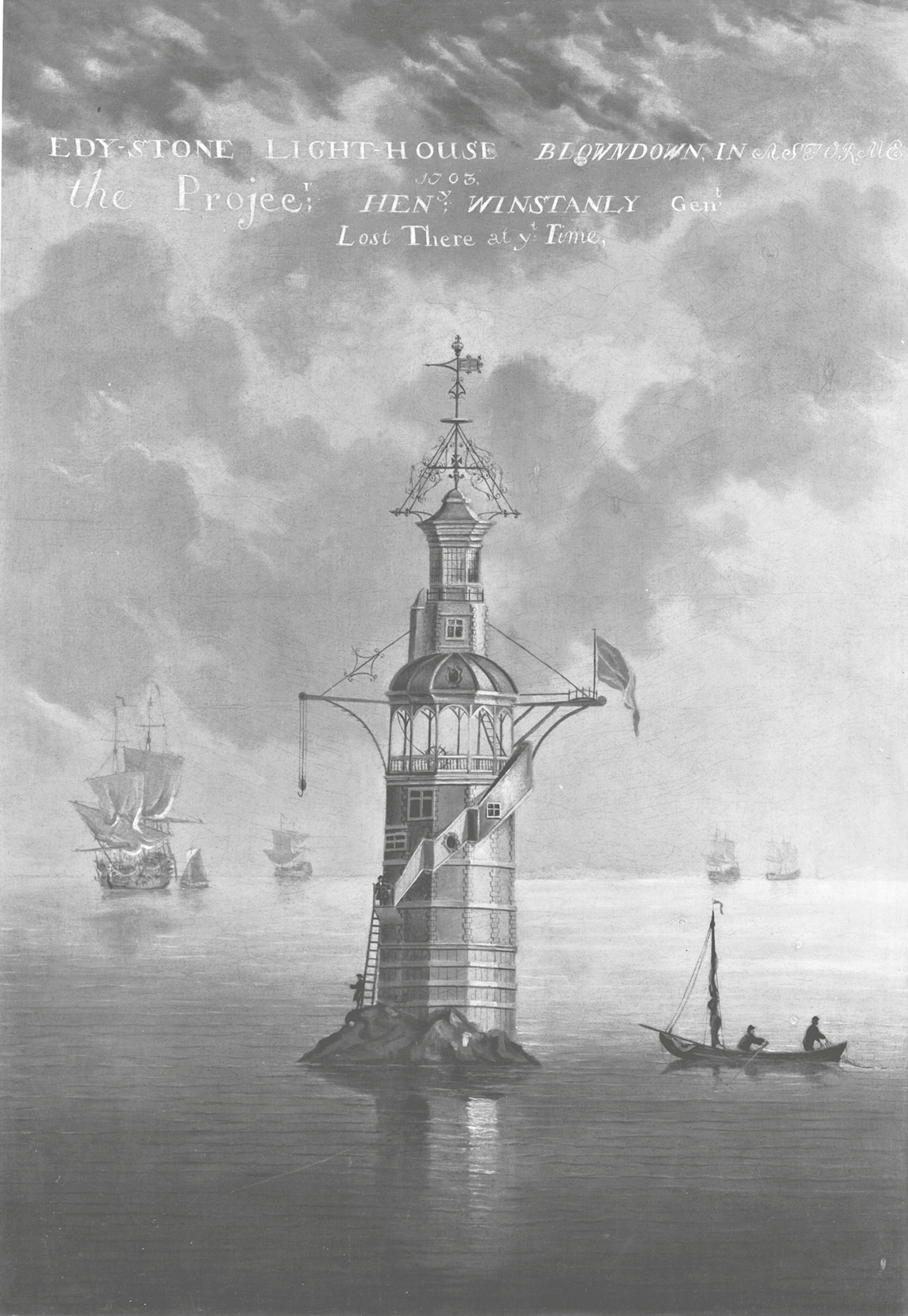

Far out to sea, at nightfall, a seventeenth-century tower creaks on its foundations. Sea sloshes and prowls below the stone base while, above the weathervane, seagulls hang momentarily before dispersing.

A small ship leaves a harbour, carrying the towers architect and a gang of carpenters. This lighthouse the first rock lighthouse in the world has been reported by sailors and its keepers as defective. It wobbles in heavy weather, leans slightly out of true and needs strengthening if it is to survive the winter gales.

As they sail, a storm develops. Though they have 13 miles to cover, south into the English Channel, there is no question of going back. I imagine the sea that evening looked like one of J.M.W. Turners visceral marine paintings, rearing and rippling in great folds. Ahead, their destination comes into view on the darkening horizon. Though by now they are used to it, the sight still initially defies the eyes. A building in the sea, standing where one shouldnt, with a light shining at its summit.

The tower appears to be hovering on the waterline, but is actually founded on a submerged reef. All hands eye it nervously. Many ships have been dragged towards this maroon, barnacled reef, which is harder than concrete and puckered like blistered tarmac, then sunk, bubbling, down the fathoms to become crashed craft deep on the ocean floor. In such stormy conditions, the crew are heading straight for it, urgently navigating for the landing-place.

For four years this tower has shown sailors where the reef lurks. Upon completion, it was immediately hailed as an impossible achievement. So certain was the architect of his lighthouses staying power that he proclaimed a desire to be inside it during the worst storm imaginable.

As they draw nearer, they begin to make out the extravagant form of the tower in more detail. On sunnier days, you can imagine fishermen disbelievingly appraising the design from their boats. A strong, cylindrical base. Sensible enough. But what about the upper stages, which seem to be wooden, octagonal and crazily decorated? What use are those ornaments where few can see them? Bent and curving ironwork and suchlike? How does the chandelier stay dry enough, out here? But, tonight, there is no time for questions. The architect is just glad the tower is still there.

Somehow, they manage a landing against the fast-running currents around the reef. They tie up the boat and hasten to the tower. In the gathering storm, its timbers creak as though shortly to rupture. At the door, the lighthouse keepers greet the men with wide eyes. Although there is a certain luxury to living this far out to sea (the tower features a gilded bedchamber and Latin inscriptions), this cannot save the drowning. Winds whip their hair and billow their coats as the intensity of the storm cranks upwards.

Over the next few days, havoc is wrought on land. Thunder booms incessantly behind the horizon. Surging wind presses men against walls, breaks carts against posts, fells wide-girthed trees, strikes down spires and chimneystacks, smacks open gates and shuts them again, races mill-sails until they ignite, clogs up rivers with ships, topples livestock in fields and batters the face of England. During the Great Storm, all believed the Apocalypse had come.

Out there, they got on with the work, hastily reinforcing and buttressing what they could. Abandoning protocol, even the architect himself hammered and sawed frantically by the last rays of daylight. But the next night, shortly before midnight, the towers candles were seen burning for the last time. As the storm grew beyond all proportion, the building began to shake madly, quaking from side to side, the iron stanchions rooting it to the reef slowly loosening. Finally, with no question of escape, the lighthouse was pitched into the sea, decisively uprooted. To a man, all perished.

1. The first rock lighthouse, English Channel, 1698

Nothing remained of this first rock lighthouse but mangled iron bars.

It is not easy to establish an enduring presence in an unstable medium like the ocean. Firm structures are seemingly incompatible with this fluid setting. Though our maritime pedigree is considerable, few traces of us linger out to sea. All too frequently, man-made things lose their buoyancy and plummet to the sea floor. Flotsam is ushered towards land and ground to pieces in coves until nothing is left, as though the sea is in a never-ending cycle of erasure.

Perhaps the allure of the sea is that it appears too restless to be permanently marked. As well as vastness, there is blankness, freely interpreted. Since the time of Francis Drake, and even before, it has offered us a majestic sense of possibility, thrusting Britains horizons outwards through trade, war and global circumnavigations. Then, the sea was an unknown realm that could lead to new territories with resources to capture and markets to exploit. The ugly undertow to historic seafaring and exploration is now recognized, but in more recent times, with oil-spills and plastics, we have despoiled the sea in other ways.

Yet today the sea remains incompletely known, not all its depths having been plumbed or probed. There is still an essential, primeval thrill in casting off from land, the excitement of discovery and transgression, and perhaps the fear that we might not make it back. Since we developed the technology to fly, the air and then space have offered us the same experience. Whether sea or space, these realms into which we stray are exhilarating because we know we are trespassers: we are present in them on the strength of our artifices, not because we can inhabit them. Nowadays, though, we look more to altitudes and space for possibilities of exploration. Our maritime past is celebrated in ballads and fine reminiscences, but for many it is just that: a past.

I was raised between two seas, the Atlantic that thrashes the Cornish coasts and the more placid Irish Sea that shimmers far away over sand-flats from the Wirral peninsula. Though my immediate roots lie in Gloucestershire, in the Forest of Dean, west of the River Severn, school holidays alternated between these two coastlines. Now, I realize this bred in me not only a subconscious affinity with the sea but also the knowledge that the sea is a thing of various guises.

A quirk of the tidal flows around the Wirral means that when the tide is out, its out. Rarely would we ever trudge the half-mile or so to paddle in its shallows; rarely, too, was the Irish Sea ever more than placid when seen from Hoylake sands in June. Nonetheless, there were chilling stories of this apparently meek, distant entity: how it could race in deceptively quickly, stranding the unwary on sandbanks, or drowning them in pulsating riptides below sheets of featureless water. I dont recall ever seeing any ship on it, either, though towards my adulthood they started building windfarms in Liverpool Bay.

1. The first rock lighthouse, English Channel, 1698

1. The first rock lighthouse, English Channel, 1698